It’s Friday and that means another blog post to show you how to master the grill for your Fourth of July cookouts! Okay. How many of you love a good pulled pork BBQ sandwich? (You can’t see me, but I’m totally raising my hand). As a southern girl, I’ve tried just about every variation of barbecue out there and let me tell you, this one rises to the top of the list. It isn’t just because of the sauce (which is Carolina-style); it’s also about the flavor of the meat!

It’s Friday and that means another blog post to show you how to master the grill for your Fourth of July cookouts! Okay. How many of you love a good pulled pork BBQ sandwich? (You can’t see me, but I’m totally raising my hand). As a southern girl, I’ve tried just about every variation of barbecue out there and let me tell you, this one rises to the top of the list. It isn’t just because of the sauce (which is Carolina-style); it’s also about the flavor of the meat!

…

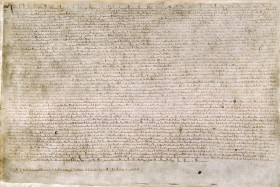

In honor of Father’s Day, we put together a short list of questions ranging from your favorite food to how you’d most like to be remembered. Answer all seven to see which founding father (or two) you have the most in common with. The answer may surprise you!

In honor of Father’s Day, we put together a short list of questions ranging from your favorite food to how you’d most like to be remembered. Answer all seven to see which founding father (or two) you have the most in common with. The answer may surprise you!

If you’re planning a Colonial Williamsburg vacation this summer, expect quite a few new kid-friendly programs in the Historic Area. In addition to bringing

If you’re planning a Colonial Williamsburg vacation this summer, expect quite a few new kid-friendly programs in the Historic Area. In addition to bringing