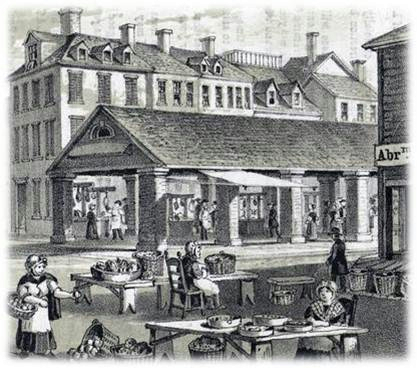

Preliminary virtual model of the Market House in 1772 © Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Digital History Center.

Over the coming months the Virtual Williamsburg team will be updating readers on the virtual model of the Market House. Continuing with the approach we previously took for the Armoury reconstruction, this model is being developed alongside the physical reconstruction to illustrate the supporting research and show the site without the concessions reflective of modern living. In this first of a series of occasional installments, we will cover the physical elements of the building, along with the initial research and planning undertaken on the details of the Market House.

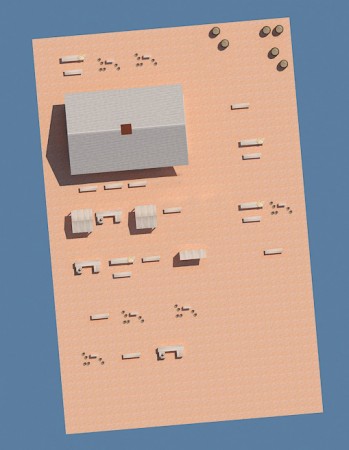

Plan of the layout of stalls in the virtual Market House © Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Digital History Center.

As part of their initial design work for the physical reconstruction, the Foundation’s architectural historians created a virtual model of the Market House in the 3D software SketchUp ™. This model was used to develop the final design for the building, and thus offered an excellent starting point for developing the 3D virtual model for Virtual Williamsburg. The basic SketchUp™ model geometry was imported into 3D Studio Max ™, and the modeling team began detailing it by adding wood and brick textures to the geometry. With the help of the architectural historians, some of the modern features necessary for the physical reconstruction were remodeled to their 18th-century appearances. These included elements of the physical building that have been added to conform to the modern practices, such as ADA requirements and product sales points. This preliminary virtual reconstruction was then added to an environmental model of Williamsburg in 1772. This provides us with the first real glimpse of the building and how it looked amongst the other 18th-century buildings on the Market Square. The research team will continue to review this updated model to ensure it reflects all of the available historical evidence, and then the modelers will undertake additional detailing and texturing, which will be described in future updates.

Planning layout of Butcher’s stalls in the virtual Market House © Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Digital History Center.

With modeling of the structure well underway, we also began to research other aspects of the original 18th-century Market House, such as butcher, fish and poultry stalls. These features will not be incorporated into the physical reconstruction, but the virtual model will provide a sense of the 18th-century market house environment, some features of which may seem unusual to modern sensibilities.

Initial layout of a stalls in the interior of the virtual Market House (roof removed) © Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Digital History Center.

The physical Market House that is being built in Williamsburg’s Revolutionary City will provide guests with a unique personal experience, and access to a wide range of 18th-century style goods and products. Virtual Williamsburg will offer a complementary experience for guests to explore and compare how an 18th-century market house functioned.

Dr. Peter Inker, Manager of 3D Visualization, Digital History Center.