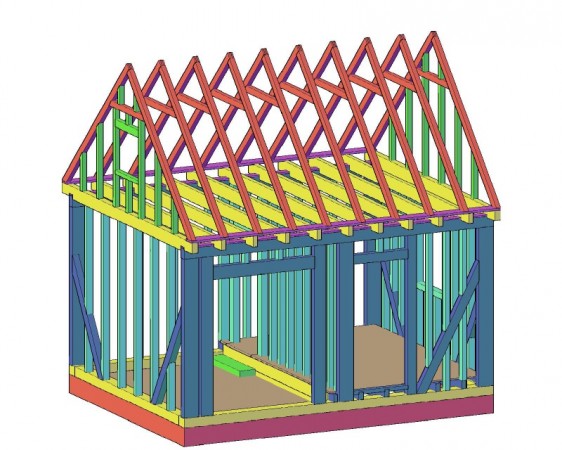

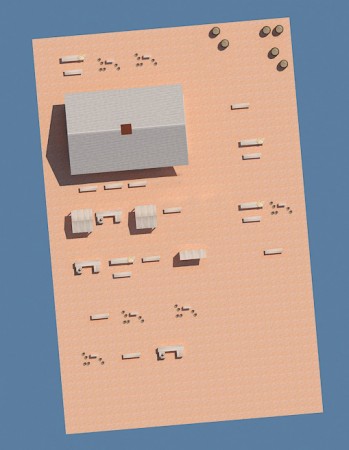

On Tuesday, May 5th, carpenters, joiners, and brick makers (all working incognito in 21st century dress), along with assorted Colonial Williamsburg staff and visitors joined in the frame-raising for Williamsburg’s 1757 Market House. No matter how many times we do it, a frame-raising never gets old! The crowd began gathering before 9, and showed remarkable fortitude as the mercury climbed above the 85 degree mark. By mid afternoon, many had retreated to the shade, but there were still a few unwavering spectators when the day was called at around 6 p.m. The action continues today, May 6th. If you missed the first “episode”, here are a few images from yesterday’s event. As always, many thanks for your interest, in-person or via the webcam. It was a great day!

[envira-gallery id=”16631″]