June 14 is Flag Day, marking the day in 1777 that the Second Continental Congress adopted the stars and stripes as America’s national banner. But it takes a bit more than the dawn’s early light to make out the origins of the flag. Still, it’s worth a try.

Let’s start with the stripes. In 1769 some Bostonians raised a flag of alternating red and white stripes to celebrate the recall of their unpopular British governor, Francis Bernard. In 1773 Boston’s Sons of Liberty flew a flag with nine red and white stripes representing the nine colonies that had attended the Stamp Act Congress.

Flag of the Philadelphia Light Horse, now the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry (ca. 1775). Photo by John Bansemer 2011.

In 1775 the Philadelphia Light Horse included thirteen silver stripes in the upper left corner of its flag. In January 1776 at the Continental army’s camp near Boston, George Washington ordered raised a flag known as the Continental Colors. It had thirteen stripes, alternating between red and white and representing the thirteen colonies.

These various flags may have been inspired by that of the British East India Company, which from 1707 flew a flag of red and white stripes. This seems a strange source: Why choose an image associated with the country whose policies you were protesting? But well into the 1770s all but the most disgruntled colonists hoped they might resolve their differences with the mother country. Even when Washington raised the Continental Colors, the Declaration of Independence was still six months in the future. Indeed, the Continental Colors featured not just red and white stripes but also, in the corner where we are used to seeing white stars in a field of blue, the Union Jack—the British flag created in 1606 by King James I. American forces flew the Continental Colors in 1776 and 1777, primarily at sea but also at some forts.

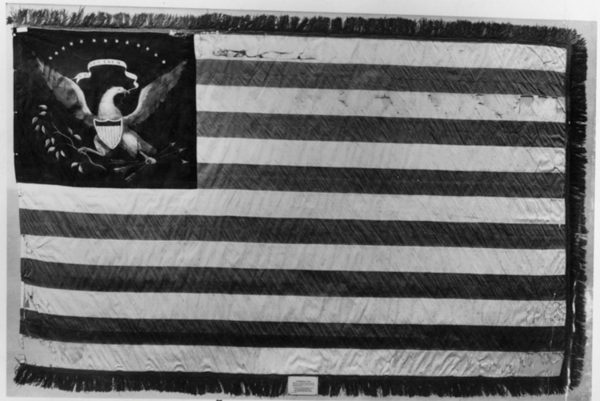

The Continental Colors (also known as the Grand Union flag).

Still, Washington recognized the problem of a Union Jack in the American flag. A few days after the Continental Colors was raised near Boston, he noted in a letter to his military secretary that the British there thought the flag was “a signal of submission.” Washington added that “by this time I presume they begin to think it strange that we have not made a formal surrender.” The Continental Congress also saw the need for a change. On June 14, 1777, Congress resolved “that the flag of the . . . United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white: that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

The Continental Colors must have influenced the stripes. We do not know why Congress chose stars, though they were common in Masonic and other imagery and Washington may have used them as his army’s flag as early as 1776.

National 13-star flag (“Jonathan Fowle” or “Castle William” flag, ca. 1781). Courtesy Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Art Commission.

The task of translating Congress’s rather vague instructions into a specific design most likely fell to Francis Hopkinson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and still a congressman from New Jersey. Hopkinson was also a poet, essayist, inventor, musician, and artist. Three years later, Hopkinson wrote a letter to the Continental Board of Admiralty noting the government had adopted a number of his designs, including several “devices for the Continental currency” and “the flag of the United States of America.” Hopkinson suggested that “a quarter cask of the public wine” would “be a proper and reasonable reward for these labours of fancy.” Hopkinson also sent a bill for “sundry devices drawings mottos etc.” The first item on it was “the great naval flag of the United States.”

Hopkinson charged nine pounds for his design of the flag. He was never paid. The Board of Treasury rejected his bill on the grounds that he “was not the only person consulted on those exhibitions of fancy” and that he was already receiving a salary from Congress. But note: The board did not at any point deny Hopkinson’s claim to have designed the flag.

Flag of General Philip John Schuyler of New York (prob. 1784 or later). Independence National Historical Park.

In any case, the particular design was not then considered a matter of great import. Early flags were made by hand and exhibited many variations. Sometimes the stars were arranged in a circle, sometimes in rows or a straight line. Sometimes the stars had four points, sometimes five or six or eight. Sometimes the flags included other emblems, such as an eagle, and sometimes words. Sometimes dots replaced stars. And military units throughout the new United States continued to fly their own regimental flags more often than the Stars and Stripes.

A family sings the Star Spangled Banner at home in this print published at the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. Library of Congress.

It was not until the Civil War that the flag became the primary symbol of American patriotism. The “Star-Spangled Banner” was played at rallies throughout the North, and “The Battle Cry of Freedom” (which begins with “Yes, we’ll rally round the flag, boys”) was also popular. It wasn’t until the end of the nineteenth century that students began to recite the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools.

The flag continued to change, adding stars for each new state. In 1958, the year before Alaska and Hawaii became states, a seventeen-year-old high school student in Lancaster, Ohio, designed the fifty-star flag as part of a history assignment. Robert Heft received a B-minus because his teacher (like most professional flag makers) assumed Alaska but not Hawaii would become a state. Heft ultimately got more out of the flag than Hopkinson: When Congress accepted his design, the teacher upped the grade to an A.

The 36-star flag was only in use from 1864-1867. Library of Congress.

Of course, neither Heft nor Hopkinson ever approached the fame of a Philadelphia seamstress named Elizabeth Griscom Ross. The story of Betsy Ross came to the fore in 1870 when her grandson William Canby read a paper on the history of the flag to the Historical Society of Philadelphia. According to Canby, in a letter to George Henry Preble, he was eleven years old when his grandmother told him and other family members how she came to create the first flag:

Washington was a frequent visitor at my grandmother’s house before receiving his command of the army. She embroidered his shirt ruffles, and did many other things for him. He knew her skill with the needle. Col. Ross [Betsy Ross’s late husband’s uncle George Ross] with… Robt. Morris, and Gen. Washington called upon Mrs. Ross, and told her they were a committee of Congress, and wanted her to make the flag from the drawing, a rough one, which upon her suggestions was redrawn by General Washington in pencil in her back-parlor. This was prior to the Declaration of Independence; and I fix the date to be during Washington’s visit to Congress from New York in June, 1776, when he came, to confer upon the affairs of the army, the flag being no doubt one of these affairs.

There is no doubt that Betsy Ross made flags. It is even conceivable that she knew Washington, if we are to believe the testimony of Canby and other family members. Ross biographer Marla R. Miller argued in her 2010 book that this experienced upholsterer was much more likely than the lawyer Hopkinson or the planter Washington to recognize, as her family attested, how much easier it would be to produce a lot of stars with five points rather than the six Washington supposedly envisioned.

“The Birth of Old Glory” (1917) depicts the myth of Betsy Ross. Library of Congress.

Still, there is no evidence that prior to its resolution of June 1777 Congress discussed, let alone turned to anyone to sew, a new national flag. It requires a great deal of speculation to jump from the evidence that Ross produced American flags to the conclusion that, as Canby claimed, her suggestions led Washington to redraw the design “in her back-parlor.”

Why, then, do we remember Betsy Ross? Perhaps America needed a founding mother to go with the founding fathers. It is a comfortably domestic story: George and Betsy get together to conceive a flag—and a nation. Wrote historian Marc Leepson:

The Betsy Ross story served as a sort of counterbalance to the message promulgated by organizations such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony’s all-female National Woman Suffrage Association [founded in 1869, the year before Canby presented his grandmother’s story]… The picture presented of Betsy Ross—doing a traditional woman’s job of sewing at home… contained the opposite message presented by the women who were outspokenly bold as they worked for the vote.

But, even if the Betsy Ross story initially spread in part as backlash to the suffrage movement, it is also possible to see Ross as a feminist heroine. Leepson admits as much, describing her as “a strong-willed woman, twice widowed, running her own successful business out of her home while caring for her children.” And, even if Ross did not remove one of the points in the flag’s stars, as Miller speculated, and even if she had no role at all in the flag’s design, Ross deserves credit for having sewn many a flag. It’s difficult to argue with Miller’s broader point that the Revolution’s success “hinged not just on eloquent political rhetoric or character displayed in combat, but also on Betsy Ross and thousands of people just like her—women and men who went to work every day and took pride in a job well done.”

Guest Blogger: Paul Aron

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly, which this post is excerpted from, as well as several other books celebrating American history, including Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly, which this post is excerpted from, as well as several other books celebrating American history, including Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

bed and breakfast in jerusalem says

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in truth used to be a entertainment account it.

Glance complex to far brought agreeable from you!

However, how can we keep up a correspondence?

During the Revolutionary War captured American Sailors were imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle. Today the castle displays a prison door that contains some graffiti-what the claim may be one of the earliest representations of the American flag outside of North America.

Arlette says

Skype has launched its website-dependent consumer beta on the

world, following launching it generally in the United states and You.K.

before this calendar month. Skype for Online also now works with Linux and Chromebook for immediate messaging connection (no

voice and video yet, these call for a plug-in installation).

The increase of the beta provides help for an extended listing of dialects to help

bolster that worldwide functionality

My typo - War of 1812

You neglected to follow through to the war of 1912.

Francis Scott Key penned what was to become our national anthem

AND Mary Young Pickersgill made the “Star Spangled Banner” with her niece and indentured servant.

In Baltimore we are really proud of this flag - The Maryland Historical Society has an exact reproduction of this quilt made by many stitchers in our area. (I was one of them)