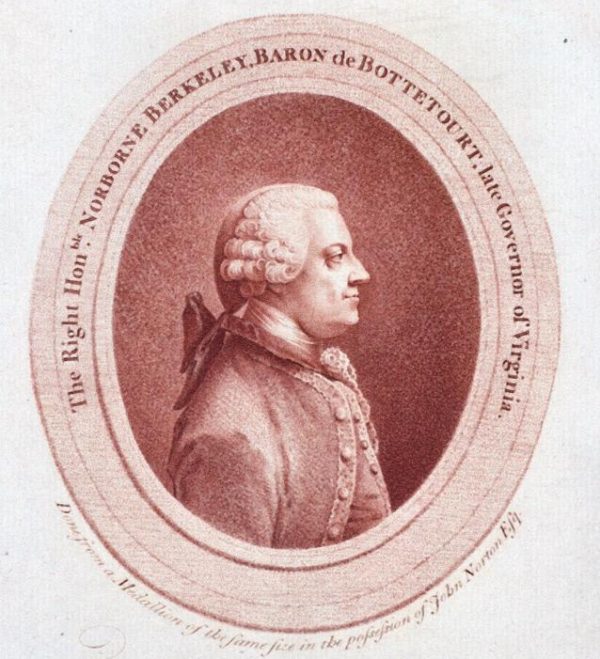

The streets of Williamsburg were still bustling with activity from the session of the General Court when Lord Botetourt emerged from the Palace and mounted an elegant chariot adorned with the Arms of Virginia and led by six cream-white horses. The recently installed governor was dressed to impress in a bright-red coat with gold braid as he headed off to the Capitol for the opening of the new session of the General Assembly. It was May 8, 1769.

The king’s subjects happily cleared the way as the chariot made the short trip down Duke of Gloucester Street to the Capitol. Although Botetourt had been warned about the Virginians’ penchant for making trouble about British policy, relations were good. Certainly better than the situation in Boston, where resistance to the Townshend Duties had been so strong that British troops occupied the city.

Meanwhile, the House of Burgesses was organizing for the session. Peyton Randolph was chosen again to serve as speaker. George Wythe, clerk of the House, swore in the new members, one of whom was his own law student, 26-year old Thomas Jefferson. The mace, a symbol of the legislature’s authority, “was laid upon the table” to indicate they were officially in session.

Lord Botetourt (full name: Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt) received the Burgesses in the upstairs Council Chamber, where the members asserted their “ancient rights and privileges, particularly a freedom of speech and debate, exemption from arrests, and protection for their estates” during the session. This represented a subtle evolution in the language of rights. Where previously the Burgesses asked the governor to respect these rights, now they were claiming them as given.

Botetourt responded with a pledge to “take care to defend them in all their just rights and privileges.” Despite the apparent comity, the Burgesses were still deeply concerned about the ongoing British policies that seemed to be designed to punish the colonies.

It took a week for trouble to bubble to the surface.

On May 16 the Burgesses adopted the Virginia Resolves, a set of four resolutions asserting colonial rights. The first declared that the House of Burgesses, with the consent of the governor and Council, had the “sole right” to tax Virginians. The second, that Virginians had the “undoubted privilege” to petition the king for redress of grievances.

The third resolve came in response to the use of a law dating to the reign of Henry VIII to drag colonists accused of challenging authority back to England to face charges of treason. This, they wrote, violated “the rights of British subjects.” Finally, they decided to pen a direct appeal to King George III asking for reassurance of these rights.

The governor was not amused.

On Wednesday, May 17, the Burgesses convened at their customary hour, 11 a.m., reviewed their petition to the king and made plans to publish the Resolves in the Virginia Gazette and send it to the other colonial legislatures.

At noon Botetourt summoned them to the Council Chamber. His message was direct: “I have heard of your Resolves, and augur ill of their Effect: You have made it my Duty to dissolve you; and you are dissolved accordingly.”

So that was it—the session was abruptly ended.

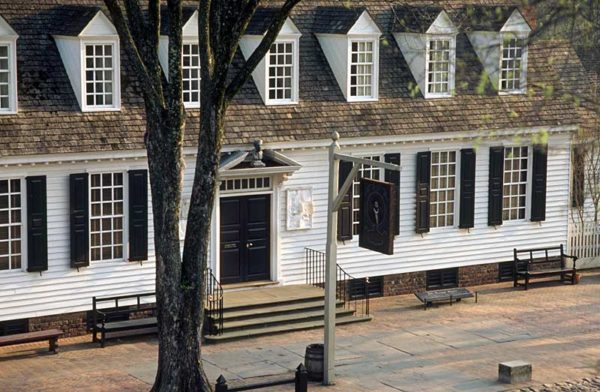

The deposed burgesses filed out of the Capitol, their official business done. But soon most joined the gathering a short distance away at Anthony Hay’s establishment, the Raleigh Tavern.

Crowded into the Apollo Room, the rump legislature was prepared to act quickly. Peyton Randolph the “moderator” and working through the day to formulate an appropriate response to what they viewed as a willful negation of their rights.

George Washington, who had served for a decade in the assembly to this point, introduced a set of nonimportation resolutions that had been circulating. They were the handiwork of his Northern Neck neighbor George Mason, who was building on efforts already underway in cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and Annapolis. The plan was a voluntary agreement to avoid British goods until the government’s policies were changed.

Washington had expressed strong support for such a scheme, believing that a boycott would not only be a suitable response to the despised Townshend Duties, but also would help to relieve the mounting indebtedness of Virginians. “Many families are reduced, almost, if not quite, to penury & want, from the low ebb of their fortunes,” he wrote to Mason in April.

In his diary Washington recorded that he stayed at work at the Raleigh Tavern until 10 p.m. What discussions of rights and duties, of justice and tyranny, must have been taking place into the night?

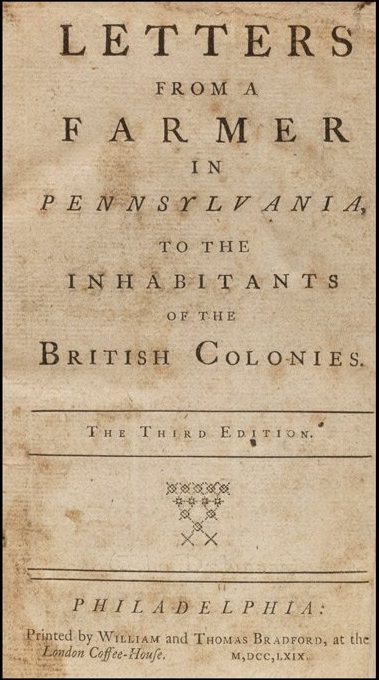

The next morning the group gathered again in the Apollo Room At some point during the day Washington bought coffee, medicine, a pair of gloves, and paid his tavern bill. But he also purchased a copy of John Dickinson’s recent pamphlet, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies, which urged the colonies to unite in resistance to British measures.

They reviewed the resolutions before them. The preamble laid out their grievances, the spate of “restrictions, prohibitions, and ill-advised regulations” emanating from Parliament. It was followed by a list of what they were willing to sacrifice until the Townshend Duties were repealed.

They pledged:

- To “promote and encourage industry and frugality, and discourage all manner of luxury and extravagance”

- To cease importing “any manner of goods, merchandize, or manufactures, which are, or shall hereafter be taxed by Act of Parliament, for the purpose of raising a revenue in America”

- Not to import a long list of enumerated goods from Great Britain, Europe, or India, among which were wine, fish, candles, sugar, watches, upholsters, lace, and leather work

- Not to import slaves after November 1

- To preserve lambs so that their wool might be put to use as homespun fabric, rather than used just for food

The pact was to be binding to each subscriber “upon his word and honour.” Eighty-eight men signed on to the Association.

But the scene was not quite as revolutionary as it might appear.

After signing the Association agreement, the members offered toasts to the king; the queen and royal family; His Excellency Lord Botetourt; and “a speedy and lasting union between Great Britain and her colonies.”

And on the following night, many of the same people, including George Washington, attended the governor’s ball at the Palace in honor of the queen’s birthday.

Meantime, Lord Botetourt wrote to the Earl of Hillsborough, secretary of state for the colonies, warning that the colonial legislatures needed to be checked before the situation spiraled out of control. It was urgent, wrote the governor, that Britain immediately “assert her supremacy in a manner which may be felt, and to lose no more time in declarations which irritate but do not decide.”

Perhaps there was still time to put the genie back in the bottle. Time would tell.

Leave a Reply