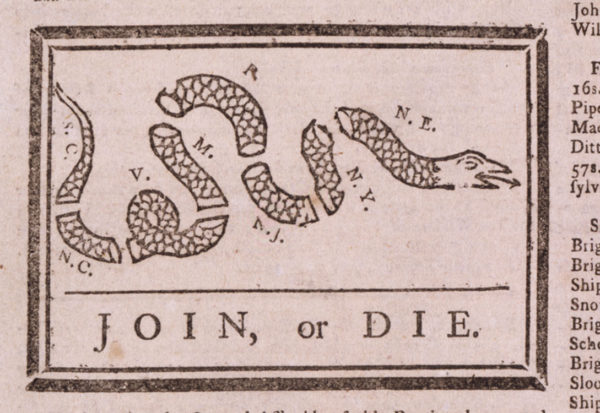

Join, or Die by Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania Gazette (1754). Library of Congress.

In 1754, with the French and Indians attacking British settlements in the Ohio Valley, Benjamin Franklin proposed “a plan for the union of all the colonies.” To illustrate the need for unity, Franklin published (and some think drew) one of America’s earliest political cartoons and perhaps the earliest symbol of a united America (albeit under British rule).

The picture, which appeared in the May 9 Pennsylvania Gazette, was a severed snake representing the disunited colonies. The caption read: “Join, or Die.” Franklin may have taken the idea from a seventeenth-century French image of a snake cut in two.

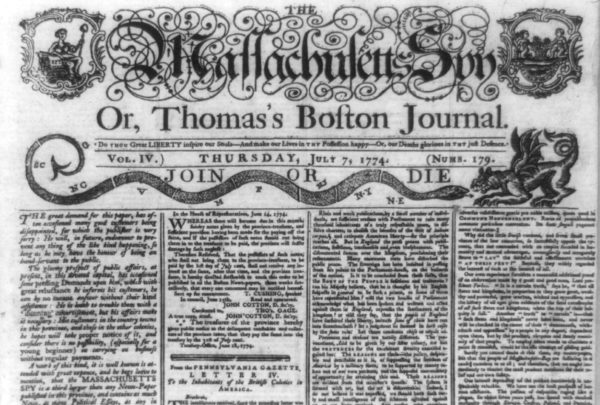

Join or Die by Paul Revere, Massachusetts Spy (1774). Library of Congress.

The plan for unity came to naught. The colonies feared each other as much as any external threat, whether French or Indian. Two decades later, though, the colonies were more united and the threat was now clearly the British. Snakes representing the united colonies appeared on the mastheads of the New-York Journal, the Massachusetts Spy, and the Pennsylvania Journal, in the case of the New-York Journal replacing the royal insignia, the king’s arms. Lest anyone mistake the meaning of the New-York Journal’s change, on January 19, 1775, a rival newspaper, Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, presented this explanation:

‘Tis true, that the arms of a good British king,

Have been forc’d to give way to a snake—with a sting;

Which some would interpret, as tho’ it imply’d,

That the king by a wound of that serpent had died.

The Massachusetts Spy depicted a segmented snake, engraved by Paul Revere, battling a dragon. Publisher Isaiah Thomas spelled it out: “The dragon represented Great Britain, and the snake the colonies.”

American officer’s “Rattlesnake & Stars” button (ca. 1778). The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

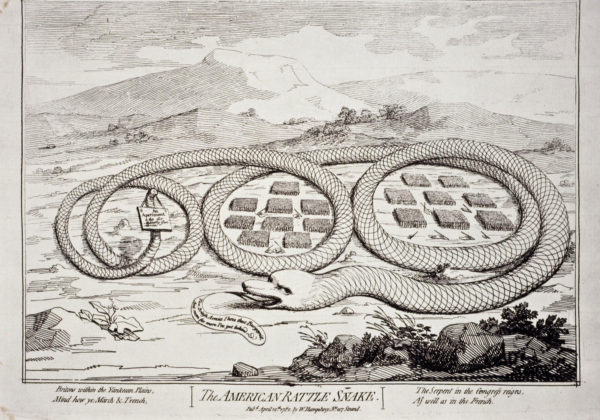

As the colonies became more united, the snakes became less segmented. After the first Continental Congress convened, the New-York Journal replaced its disjointed snake with a united one and inscribed on its body: “United now alive and free.” An officer’s button purportedly found near a 1778 battlefield in Monmouth, New Jersey, displayed a rattlesnake encircling thirteen stars. In British illustrations, too, snakes became popular symbols of America. A 1782 etching attributed to James Gillray shows the American snake coiled into three sections, two encircling British forces that had surrendered and a third advertising “An apartment to lett for military gentlemen.”

The American Rattle Snake, attributed to James Gillray (1782). The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Rattlesnakes became especially popular, appearing on various state flags as well as navy and army flags and often coiled and ready to strike. Below the snake were often the words “Don’t tread on me.” The phrase has sometimes been attributed to Franklin, probably because of his role in promulgating the “Join, or Die” snake, but most historians credit them to Christopher Gadsden, a leading South Carolina patriot and a member of the Continental Congress.

At the very least, Gadsden must have liked the image, since in February 1776 he presented a flag with it to the South Carolina provincial Congress. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, what came to be known as the Gadsden flag was adopted by libertarians and then Tea Party activists.

In one sense, the snake was a strange choice for Americans. “To those familiar with the Judeo-Christian tradition,” wrote historian Lester Olson, “the image of the snake ought to have had connotations of wickedness, yet here was a predominantly Christian culture that seemed to welcome the image as a representation of themselves.”

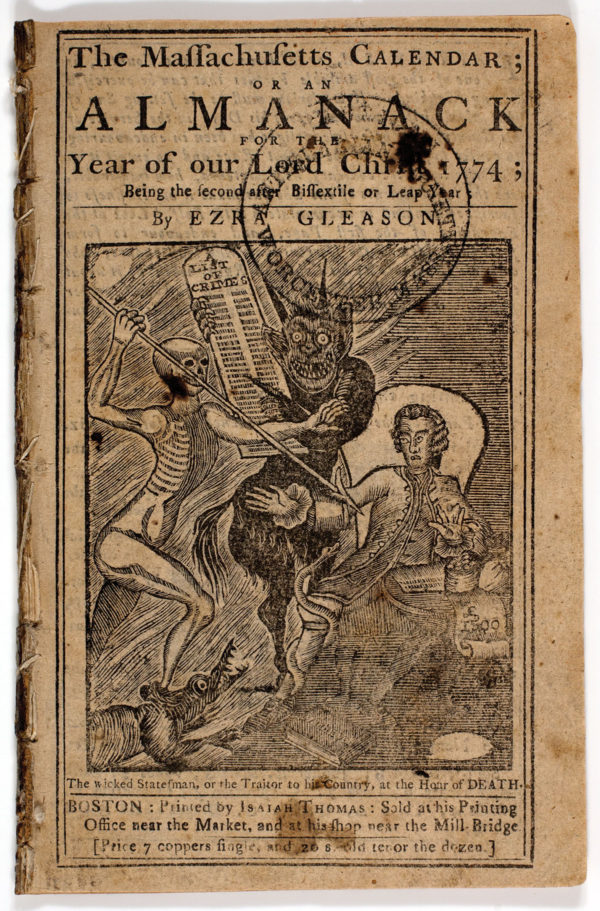

The Wicked Statesman, or the Traitor to His Country at the Hour of Death, cover of Massachusetts Calendar; or an Almanack for the Year of Our Lord Christ 1774 by Ezra Gleason, Boston, 1774. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

Even as Americans embraced the snake image, snakes continued to connote wickedness. In 1774, the snake not only appeared on the Massachusetts Spy’s masthead but also on the cover of an almanac, also published by Thomas. On the almanac the snake is wrapped around Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s leg and is a symbol of evil. The Spy went so far as to explicitly deny that the snake on its masthead had

anything to do with the one in the Garden of Eden, explaining in its September 15, 1774, issue that “the snake ye with wonder behold, / Is not the deceiver so famous of old.”

Why, then, use the snake at all? Partly it may have been because its long and winding shape seemed similar to that of the colonies—and later the states—along the coast of North America. In 1775, a Pennsylvania Journal writer noted that the rattlesnake, like America, “never begins an attack, nor, when once engaged, ever surrenders.” Best of all, said the Journal writer, “the Rattle-Snake is found in no other quarter of the world besides America.”

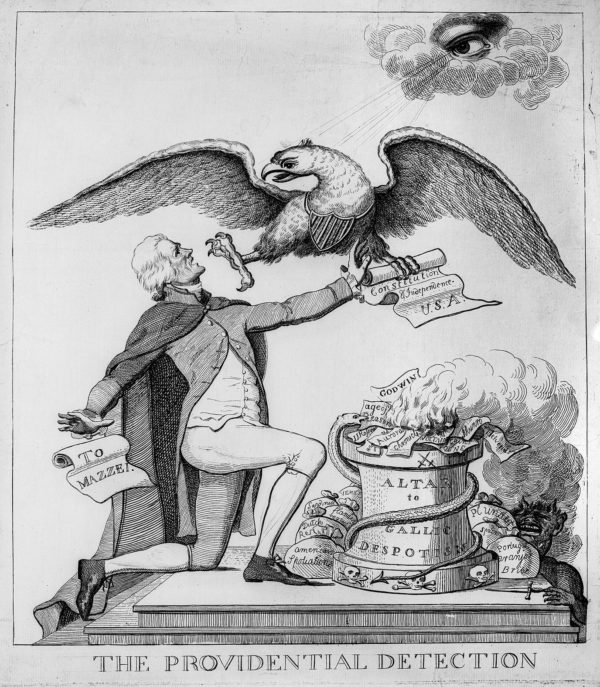

The Providential Detection (ca. 1800). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

Eventually, though, snakes simply wouldn’t do. After the Revolution, they were used less and less frequently as a symbol of America, and, when they were used, it was often alongside the increasingly ascendant eagle. Indeed, the snake was sometimes again a symbol of treachery. Around 1800, for example, an anti-Jefferson print portrayed the eagle protecting the Constitution while Jefferson tried to burn it on the “Altar of Gallic Despotism.” A snake was firmly wrapped around the altar.

Guest Blogger: Paul Aron

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly, which this post is excerpted from, as well as several other books celebrating American history, including Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly, which this post is excerpted from, as well as several other books celebrating American history, including Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

My understanding is that part of the snake symbolism originated from a folk belief that if a snake was cut into pieces, it could still live as long as the pieces were put back alive before sunrise. Especially in the context of Franklin’s snake, that would be a powerful symbol of the urgency and necessity of uniting before it becomes too late, and unity is impossible.

Wonderful lesson today! The “Don’t Tread on Me” and “Join, or Die” illustrations are still incredibly powerful symbols.