A stylish female figure can be seen in many photographs documenting the architectural team who undertook the restoration of Williamsburg’s historic district. She often stands out as the one lone woman amidst the group of men.

In some photos, she is walking the grounds of Virginia plantation homes such as Mount Airy and Shirley and discussing features of the buildings and landscape. In others, she is overseeing the installation of specific elements, such as the unicorn atop the Governor’s Palace gate. This woman was far more than just a companion or assistant to the men. She played her own vital role in giving birth to Colonial Williamsburg.

While many of the groundbreaking contributions to the historic preservation movement originated with the group of male architects, contractors, and draftsmen working at Colonial Williamsburg, the building interiors that first delighted tourists owe their appearance to the work of this female trailblazer, Susan Higginson Nash (1893-1971). The interiors of Colonial Williamsburg buildings, first opened to the public in the 1930s, influenced American taste and inspired an early line of model period rooms in the “Williamsburg style.”

A good friend of architect William G. Perry, Nash came to be selected for the role of interior decorator by Andrew Hepburn due to her knowledge of and interest in Southern architecture. She did not possess professional experience as a designer but had an artistic background and formal training with artists Dodge McKnight and Charles Hopkinson. Later she became a member of the American Institute of Decorators.

Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin advised his architectural team that he wished to have a woman with a Southern background to participate in the process of selecting appropriate period furnishings, paint colors, and textiles for the restored buildings. Although born and raised in Boston, Nash seemed like a perfect fit when the woman originally selected for the role, Mrs. Schenck, fell ill.

Nash knew the team of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn well, had a cousin Mrs. F. Otway Byrd, who lived at Upper Brandon, and had previously made several visits to Virginia. She also had an understanding of the detective work and connoisseurship required to select appropriate antique furniture and accessories.

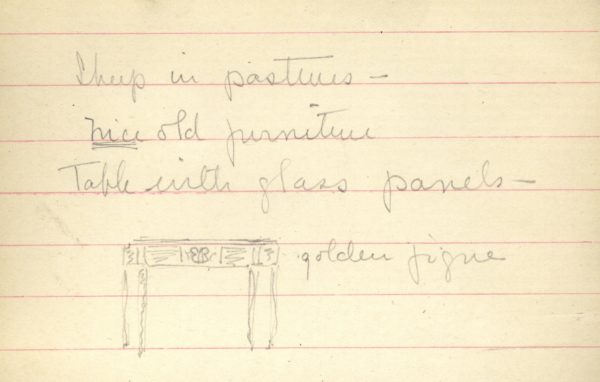

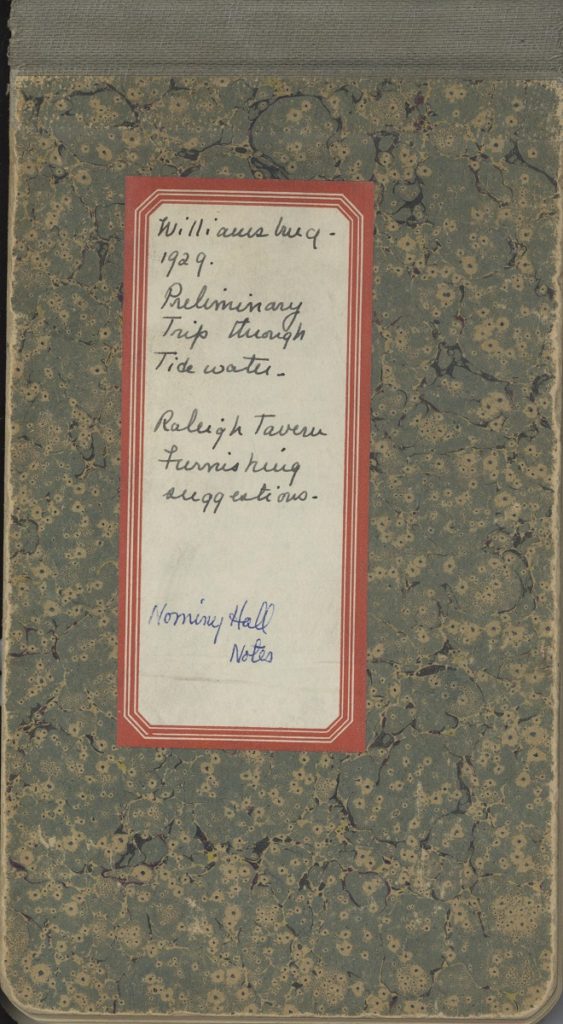

One of Nash’s first assignments involved researching and suggesting appropriate furnishings for the Raleigh Tavern. The Capitol and the Governor’s Palace soon followed as major interior design projects. Nash consulted colonial inventories, invoices, advertisements, newspapers, architectural texts, and correspondence to aid her in making authentic selections for wall treatments and furniture. She also embarked on an extensive buying trip to England in 1936 to locate furniture and decorative accessories suitable for the Governor’s Palace. Architect William G. Perry and Mr. Francis Lenygon of the firm of Lenygon & Morant accompanied her and, together, the team selected over 800 items for the Palace.

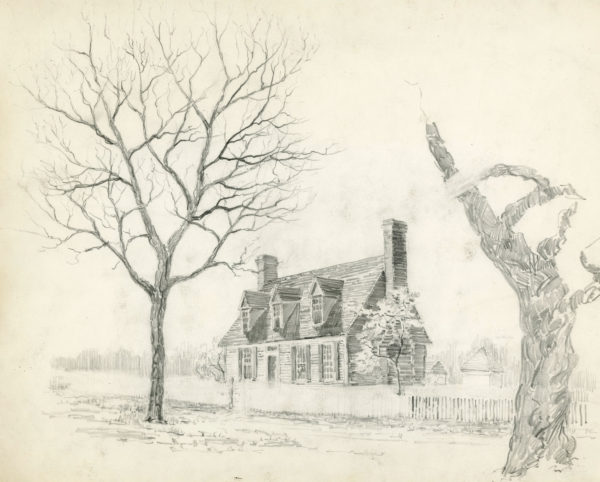

Paint scrapings taken from sites in Virginia known to have original 18th-century paint with no over painting, such as Little England, aided Nash in determining appropriate color schemes for each of the three exhibition buildings. While some conjecture occurred in completing furnishing schemes, Nash attempted to adhere to any existing records and physical evidence as closely as possible.

The resulting aesthetic appeal of these first period room installations introduced the concept of a “Williamsburg Style.” In the November 1937 issue of House and Garden magazine, architects Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn debuted designs for three versions of Williamsburg homes modified for modern living. Nash’s room installations provided inspiration for the magazine’s recommendations on how to furnish modern versions of colonial homes. The popularity of the interior design plans in this House and Garden issue led to model period room displays at numerous American department stores, such as Woodward & Lothrop in Washington, D.C.

Nash was also instrumental in forming a Ladies’ Advisory Committee to assist the architects in their work. Composed of women from Williamsburg, Richmond, and neighboring counties, this committee paved the way for visits by the architectural team to many Virginia homes such as Mount Airy, Gaymont, Ampthill, and Shirley. Quite a few of the committee members lived in historic properties and gave the team a warm welcome and invitation to study original paint colors, architectural details, building materials, and surviving gardens at their residences.

They also acquainted the team with the attitudes of “old Virginia” and served as allies and advisors when opposition to the restoration work arose. Nash noted that, “The owners of the great houses in the neighborhood of Williamsburg have been among the Restoration’s greatest friends. I do not know how to thank them for the generosity, friendliness and interest that they have shown in helping us to solve the problems which they in turn have adopted as their own.”

During research trips to the sites, Susan Nash carefully documented the architectural and landscape features via photography. A selection of Nash’s photographs from these trips to study architectural precedents, as well as of the progress of work at Colonial Williamsburg, are preserved at the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library. A portion can be viewed online at the Highlights of the Susan Higginson Nash Photograph Collection. Nash’s large visual record of fieldwork visits to sites such as Mt. Airy, Gaymont, Shirley and Little England illustrate the detailed detective work that preceded both architecture and interior design decisions at Williamsburg.

A pioneering figure in the analysis of historic paint layers, Susan Nash inaugurated the Williamsburg paint palette. Introduced in 1936 by John Masury Paint Company, the palette consisted of approved interior and exterior paint colors used during the restoration of buildings in Williamsburg. Homeowners wishing to replicate the appearance of a particular period room or building façade could consult the palette and select hues such as Apollo Room Blue, Governor’s Palace Office Yellow, or Davidson Shop buff.

Nash based the palette upon painstaking research conducted from studying historic documents and analyzing actual samples taken from a variety of extant buildings. She discovered that many of the colonial colors were often quite vibrant and used to provide harmonious contrasts between woodwork details and larger wall expanses. Nash believed that “study of… color and texture must precede execution and be so considered that it shall include the scheme of the foreground, and the scheme of sequence from room to room.” Her efforts to harmonize the sequencing of color and furnishings in Williamsburg’s exhibition buildings had a profound influence on interior design trends of her era.

Nash’s last major project for Colonial Williamsburg involved working as a consultant on interior design work for the Williamsburg Inn. McCutcheon, a high-end New York retailer, oversaw the selection of furnishings for the Inn but brought Nash in to provide recommendations on such elements as wallpaper and draperies. John D. Rockefeller Jr. described the end result of the team’s efforts as “satisfying, beautiful, and homelike.”

A meeting of the American Institute of Decorators at the Inn just four days before its opening on April 3, 1937 confirmed Mr. Rockefeller’s assessment. In 1940, Nash received word that her services would no longer be needed due to the formation of a curatorial role to oversee exhibition building interiors. She returned to the Boston area, where she continued to build her interior design career through work on a variety of projects, ranging from the Wellesley College dormitories to the Rare Book Library at Harvard University. Susan Nash died on July 25, 1971 with a well-deserved reputation as a talented advisor for furnishings at historic sites.

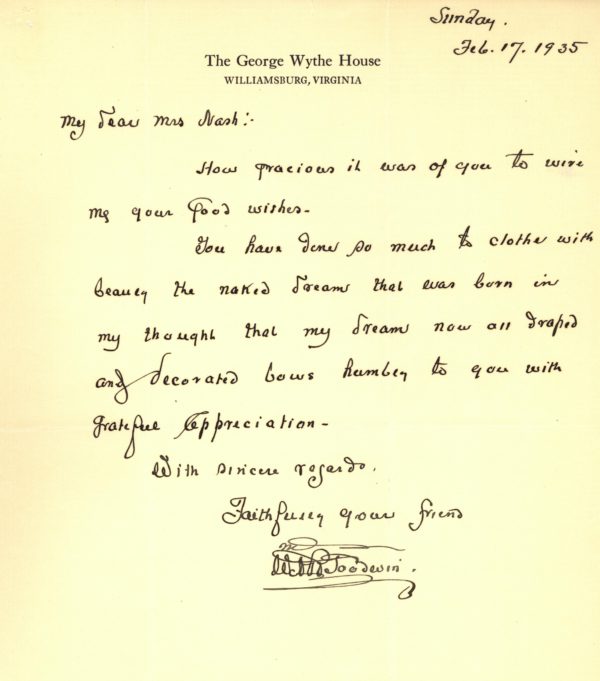

A letter from Dr. Goodwin written in 1935 expressed his deep appreciation for Nash’s abilities: to “clothe in beauty the naked dream that was born in my thought.” This is indeed Nash’s greatest contribution – bringing the intimate settings of 18th-century daily life alive once again for the education and appreciation of the first several decades of visitors to Colonial Williamsburg. Although many exhibition building interiors have since been reinterpreted based upon new research discoveries, Susan Nash’s first period room installations laid the groundwork for further investigation of original paint colors, fabrics, and furnishings.

Guest Blogger: Marianne Martin

Marianne Martin is a Visual Resources Librarian at the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg. She works behind the scenes to care for the historical images housed in the library and assists both Colonial Williamsburg staff and outside researchers with locating visual materials to support their projects. The opportunity to learn more about the people, places, and events featured in the large collection of historical photos leads to fascinating detective work and new discoveries each day. When she first visited Colonial Williamsburg on an eighth grade class trip, little did she know that she would one day have the privilege to work at the museum!

Mary Jablonski says

I echo Kirsten Moffit’s comments. and am glad to see the woman who really initiated architectural paint research given her due. Yes, she made mistakes but then who does not. Thank you for a great post and filling in the details on her work and life.

Excellent post! Ms. Nash was an early pioneer in the field of architectural paint research, and it is nice to finally see her get the credit she deserves! Her meticulous methods paved the way for Colonial Williamsburg’s Materials Analysis Lab, where we use methods of modern science to learn about 18th century color. I think Susan Nash would have been proud. This was a truly fantastic post spotlighting a very important person- thank you!

Tess says

This post is delightful. Dream job!