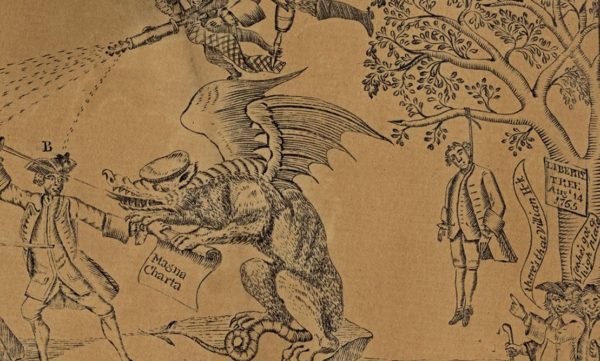

Detail from A View of the Year 1765 by Paul Revere (1765). Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

In this excerpt from Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly. we look into how an everyday part of nature was used as a potent symbol of freedom. Though largely forgotten today, to the American patriots of the 18th century, liberty trees and liberty poles were representations of their cause at least as prominent as liberty bells or lady liberties.

Liberty trees just made sense: In a continent covered by forests, trees offered colonists shelter and warmth and the promise of a new start. Trees might also have reminded Revolutionaries of stories of earlier rebels: Think Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest. And many Connecticut patriots could recite the legend of the Charter Oak, a tree in Hartford where in 1687 colonists had allegedly hidden their charter to prevent the king’s agents from seizing it.

It was in Boston, however, that the liberty tree took root. Specifically, it was at the intersection of Essex and Newbury Streets. Here stood a large elm tree known—until 1765—as the Great Elm or the Great Tree. On August 14 of that year, Bostonians woke to find hanging from one of its branches an effigy of Andrew Oliver, whose job was to distribute the stamps authorized by the much-despised Stamp Act. That evening, a crowd led by shoemaker Ebenezer Mackintosh paraded the dummy though the streets of Boston and set it afire near Oliver’s house. The next day, Oliver sent word through friends of his resignation.

A View of the Year 1765 by Paul Revere (1765). Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

On September 11, news reached Boston that in London William Pitt, a Stamp Act opponent, was to become prime minister. Quickly, a large copper plate was affixed to the tree’s trunk. On the plate were the words “The Tree of Liberty.”

Over the next decade, Boston’s Liberty Tree was the site of numerous patriot demonstrations. In November 1765, crowds hung in effigy a supporter of the Stamp Act. Paul Revere’s engraving pictures him on the tree while a dragon, symbolizing the Stamp Act, threatens the Magna Charta. In May 1766, when news reached Boston that the Stamp Act had been repealed, the Boston-Gazette reported the tree was “decorated in a splendid manner.”

The Bostonian’s Paying the Excise-Man, or Tarring & Feathering, attributed to Philip Dawe (1774). The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

In January 1774, a crowd enraged by Parliament’s Tea Act tarred and feathered a British customs official. Philip Dawe’s print of the scene shows in the background both the Boston Tea Party and the Liberty Tree, which in this case has become a gallows. Johann Martin Will’s print, also published soon after the Boston Tea Party, symbolizes the British closing of Boston’s port by placing Bostonians in a cage hanging from the Liberty Tree.

The Bostonians in Distress by Johann Martin Will (1774). The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

In 1775, the British army occupied Boston, and loyalists seized the opportunity to chop down the tree. By then, though, the tree’s seeds had spread beyond Boston. John Dickinson honored it in his 1768 “Liberty Song” and Thomas Paine in his 1775 poem “Liberty Tree,” which reads in part:

From the east to the west, blow the trumpet to arms,

Thro’ the land let the sound of it flee,

Let the far and the near,—all unite with a cheer,

In defence of our Liberty tree.

During the war, many New England soldiers carved liberty trees on their powder horns. James Pike’s powder horn depicts not only the tree but the Battle of Lexington, with the British soldiers labeled “Regulars, the Aggressors” and the patriots “Provincials Defending.”

James Pike’s powder horn (1776). Chicago History Museum.

Outside of New England, liberty poles often played the part of liberty trees. In New York City, patriots erected a liberty pole near the common to celebrate the repeal of the Stamp Act. British soldiers repeatedly cut it down, often leading to skirmishes. The pole provided New Yorkers with an advantage their fellow patriots in New England lacked: Unlike trees, new poles could quickly replace old ones.

New York’s patriots also learned to protect their pole with iron, as can be seen in Pierre Eugène Du Simitière’s drawing Raising of the Liberty Pole in New York City. Liberty poles were often topped by liberty caps, a symbol of emancipation of slaves dating back to Roman times.

Raising of the Liberty Pole in New York City by Pierre Eugène Du Simitière (ca. 1770). The Library Company of Philadelphia.

In 1787, Thomas Jefferson wrote, metaphorically but surely with an awareness of the tree’s history, that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” At the time, Jefferson was in France, where the liberty tree became one of the main icons of the French Revolution.

Back in America, poles cropped up in Pennsylvania during the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794 when farmers protested a federal tax; after the passage of the 1798 Sedition Act, which authorized fines and prison for those who defamed the government; and as campaign symbols during the 1820s. (Andrew Jackson, whose nickname was Old Hickory, favored poles of hickory; Henry Clay of Ashland, Kentucky, used ash poles.)

As a campaign symbol, liberty poles—and trees—had already lost much of their iconic power. Why did these icons fade away while others like liberty bells or lady liberties endured? At least for the trees, one reason is that those that weren’t cut down eventually died.

Historian Alfred Young has argued that it wasn’t just the British but also American conservatives who, at least metaphorically, chopped down the trees. Liberty trees and poles were often gathering points for radicals. The skirmishes that took place around them were often led by working-class artisans like shoemaker Ebenezer Mackintosh, hardly one of our best-known founding fathers, and the trees and poles were embraced as symbols less by generals than by soldiers like the farmer and militiaman James Pike. That liberty poles became prominent symbols of the French Revolution also scared American conservatives. Whatever the reasons, by the mid-19th century, the trees and poles were largely gone from America’s memory.

Guest Blogger: Paul Aron

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly and several other books celebrating American history, including most recently Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly and several other books celebrating American history, including most recently Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

How interesting. Do we know if there was ever a liberty tree or liberty pole in Williamsburg?

Yes! There was a liberty pole that was more threat than ideal. In November 1774 Norfolk merchant James Parker (a loyalist) wrote, “At Williamsburg there was a Pole erected by Order of Col. Archibald Cary, a strong Patriot, opposite the Raleigh tavern upon which was hung a large mop & a bag of feathers, under it a barrel of tar.” You can read more here: bit.ly/2oY6n7t