On this day in history, in 1770, the Boston Massacre, a major milestone on the road to revolution, took place. The first published report in Williamsburg came three weeks later, with rumors in William Rind’s Virginia Gazette of a “fray” resulting in British soldiers being driven out of town by angry inhabitants. By the next issue, new details painted a more somber picture, and the incident was already being referred to as a “massacre.”

In this excerpt from Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly, we pick through some of the mythologizing that quickly occurred as opponents of British policies sought to use the event to their advantage. Read on, and you’ll also find out how our Silversmiths and engravers commemorate the event.

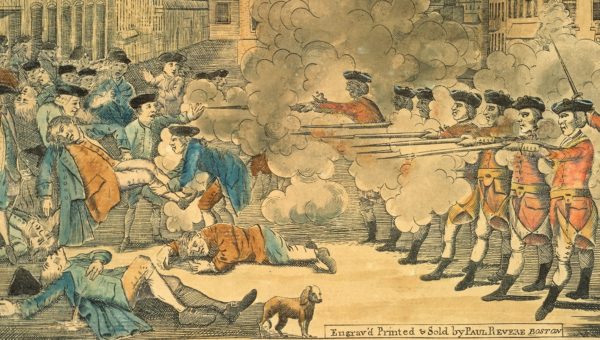

The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King Street . . . by Paul Revere (1770). The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Paul Revere’s famous engraving, perhaps the most famous illustration of the Revolutionary period, leaves little doubt about who was to blame for what Revere called “the bloody massacre perpetrated in King Street.” The illustration shows British soldiers in a line, firing point-blank at a crowd of unarmed townspeople, apparently at the order of their captain, Thomas Preston.

In reality, the origins of the Boston Massacre are much murkier—and so are the origins of Revere’s illustration, which the famed silversmith may very well have copied from another artist’s work.

First, the Massacre. Soldiers did indeed shoot Bostonians on that evening of March 5, 1770, killing three on the spot and mortally wounding two others. To patriots like Revere and Samuel Adams, the violence was the direct and inevitable result of British oppression, in particular that of the British soldiers who were in Boston to enforce unpopular trade regulations. The victims were the first heroes of the Revolution to come. Until 1784, many Americans celebrated their independence on March 5 rather than July 4.

Apprentice silversmith Parker Brown holds the hand-copied engraving of Paul Revere’s famous rendering of the Boston Massacre. The engraving was made by Lynn Zelesnikar in the shop several years ago, and from it are made what may be the most accurate copies of Revere’s original ever made.

- To reproduce Revere’s original, the first step is individually printing a black-and-white version.

- Lynn hand paints each print, then they are finished with a black, period-looking frame. Interested? Contact the Golden Ball to order one for your favorite history lover. The cost is $375.

Not surprisingly, the British had a different view of the events. Some London newspapers suggested the Bostonians were after the king’s coffers in the customhouse. Others accused patriot leaders of planning the incident, perhaps even with the hope of turning its victims into martyrs.

To loyalists, this was not the Boston Massacre but “an unhappy disturbance.” A mid-nineteenth-century illustration by Alonzo Chappel presents the deaths as the result of a chaotic mob scene rather than anything planned by either the soldiers or the patriots. In Chappel’s illustration, the soldiers are disorganized, Preston appears to be signaling for them to stop firing, and some of the Bostonians are carrying clubs and clearly threatening.

Boston Massacre, engraving by an unidentified artist after Alonzo Chappel. National Archives.

The evidence presented at the soldiers’ trials seems closer to Chappel’s version than Revere’s. The defense attorney, none other than future president John Adams, argued that the soldiers acted in self-defense. One defense witness was Dr. John Jeffries, a friend of Samuel Adams, who had treated Patrick Carr, one of the victims. Jeffries testified that Carr, as he lay dying, told him he’d heard many voices cry out to kill the soldiers. Carr added “that he did not blame the man whoever he was, that shot him.” The jury acquitted Preston and six of the soldiers of murder and found two other soldiers guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter.

Historians continue to debate the verdicts, but there’s no doubt that in making his engraving Revere was more interested in the propaganda value of a massacre than in accurately portraying the details. The “Butcher’s Hall” sign on a coffeehouse popular with British officers was clearly meant as a barb. The casualty list at the bottom of the illustration is inaccurate, identifying as mortally wounded two who survived. The illustration seems to have entirely omitted Crispus Attucks, one of the victims and an escaped slave who was the son of an African father and Native American mother. If Attucks is in the picture at all, he has been turned into a white man.

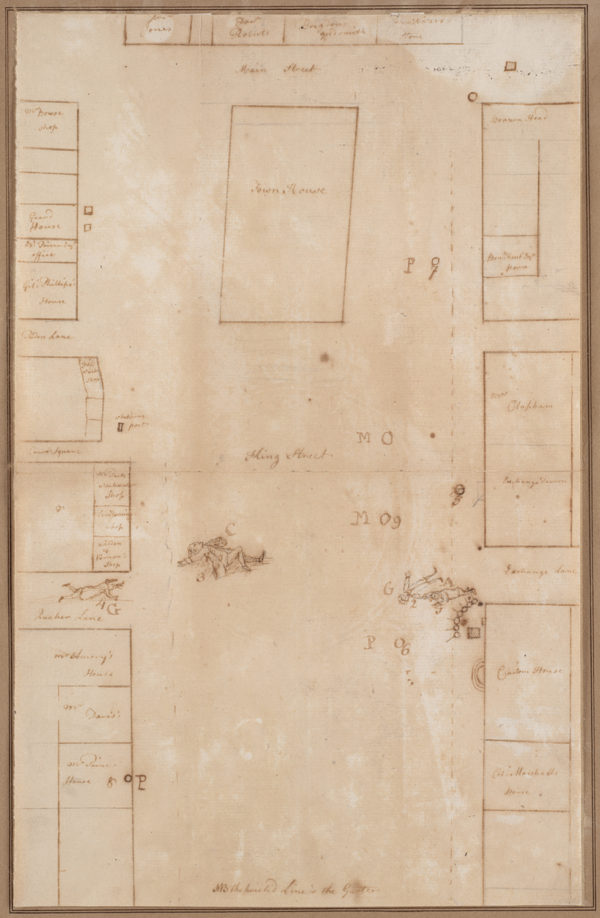

Sketch of Boston Massacre by Paul Revere (1770). Boston Public Library.

Revere himself presented a more accurate view of the event in a pen-and-ink diagram plan of King Street. He may have prepared this for use at the soldiers’ trials, though it does not appear to have been used in court.

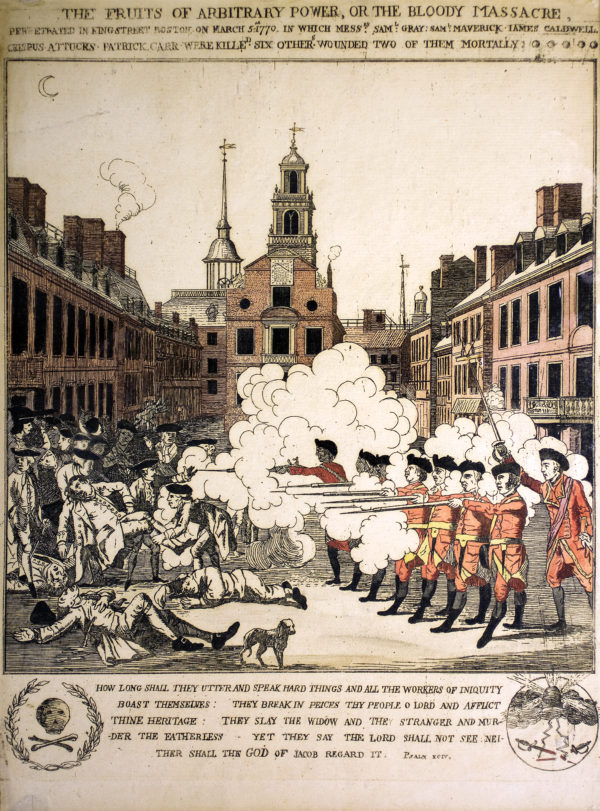

As for the famous engraving’s origins, Revere may have copied it from the Boston painter and engraver Henry Pelham. The image generally attributed to Pelham is certainly very similar to the one generally attributed to Revere. The most noticeable differences are the headings and, in Revere’s, the addition of the entirely fictional “Butcher’s Hall” sign.

Fruits of Arbitrary Power, or the Bloody Massacre by Henry Pelham (1770). Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

On March 29, 1770, Pelham wrote to Revere accusing him of copying the work. “I thought I had entrusted it in the hands of a person who had more regard to the dictates of honour and justice than to take the undue advantage you have done of the confidence and trust I reposed in you. But I find I was mistaken,” Pelham angrily wrote.

It was as bad as if, Pelham added, “you had plundered me on the highway.” A week later, Pelham advertised his print in Boston newspapers, describing it as “an original print . . . taken from the spot.” There’s no record of Revere responding to Pelham. In Revere’s defense, it was common at the time for engravers to take designs wherever they found them without the original artist’s permission. In any case, Revere must have somehow mollified Pelham. Four years later, in 1774, Revere was doing engraving work for Pelham.

Guest Blogger: Paul Aron

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly and several other books celebrating American history, including most recently Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly and several other books celebrating American history, including most recently Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

Leave a Reply