As the father of a one-year-old daughter, I try to be “up” on all things Disney, though I’m far from an expert. But I’m also a curator of costumes and textiles, and sometimes the costuming catches my attention. When my wife asked me about the time period of the attire in Disney’s new “Beauty and the Beast” movie, I decided to dive in. Follow me as we take a tour through some of the fashions that may have inspired costume designer Jacqueline Durran for the garments worn in the movie.

Like the opening scene of the animated version, Emma Watson as Belle enters the village of Villeneuve attired in a blue bodice and petticoat, striped pocket, and checked apron. The bodice resembles an Elizabethan kirtle, a garment made with stiffened layers of buckrum that laced commonly on the sides, provided support for the bust, and often had skirt panels attached at the waist.

Orazio Gentileschi, The Lute Player, c. 1612/1620, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, National Gallery of Art

The image above from the 17th century appears to show a kirtle. Unfortunately, we do not have any in our collections. Surviving examples from this early time period are extremely rare.

Watson wears a colorful striped pocket tied around her waist in which she places bread that she buys from the village baker. From the 17th through 19th centuries, women typically wore pockets separately, tied around the waist, hidden under their petticoats or skirt. A slit in the petticoat allowed access to the pocket from the exterior.

Several fantastic patchwork pockets, including the example above, from Albany, New York dated 1810, are on display in the newly opened exhibition Printed Fashions: Textiles for Clothing and Home in the Gilliland Gallery in the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

As a daughter of a working class tinker and inventor, Belle wears a common checked apron. Women had many options for aprons, from fine and fancy to coarse and plain. Belle’s checked apron would be very serviceable and easily hide stains, making it a very practical garment for her to own and wear. The one pictured above is a blue and white check linen piece from 1776.

Belle’s iconic yellow gown certainly captures the heart of young aspiring princesses. The gown has a lightly structured bodice with a modest neckline with multiple layers of fine net and silk organza to create fullness and is sleeveless.

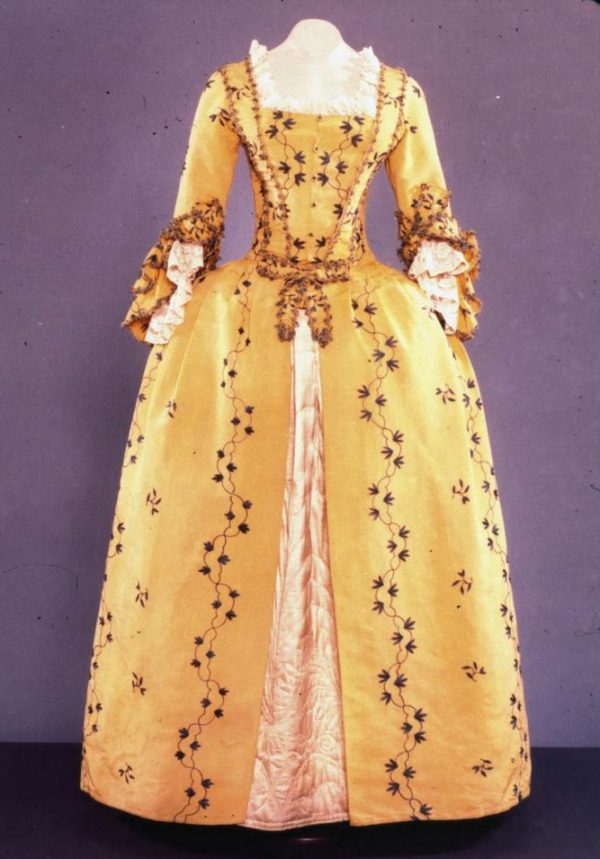

Colonial Williamsburg has in its collection an English gown dating to the 1770s made from bright yellow silk and embroidered with blue vines and flowers.

While 18th-century gowns generally had three-quarter length sleeves, costume designer Jacqueline Durran may have gained inspiration from gowns that date to the mid-19th century with their full bell-shaped skirts that are cut low off the shoulders and do not have sleeves. The example above, an 1840s silk taffeta gown brocaded with silk, is in Colonial Williamsburg’s collections.

One of the most interesting garments in the production is the suit worn by the Beast in the sweeping dance scene with Belle. Beast wears a blue “court” style coat fully embroidered in white. Coats in this style date typically to the last quarter of the 18th century and were usually embroidered as flat panels. Tailors would cut out the pieces and assemble the suit to fit their customer.

Several of these fancy dress suits, such as the purple embroidered example above, survive in the collection at Colonial Williamsburg.

The infamous Gaston played by Welsh actor Luke Evans wears a striking red coat trimmed in gold with matching waistcoat and brown breeches. While the coat takes the cut of a 1730s or 1740s, the narrow cuffs and collar resemble coats from the later 1770s.

A very plain example of a red coat dating to the 1770s and worn by Amos King of Massachusetts survives in the collection at Colonial Williamsburg.

The story of Beauty and Beast was first published in the mid-18th century, but anthropologists and folklorists trace the origins of the fairy tale back nearly four thousand years. It is truly a “tale as old as time,” with time being undefined. Costume designer Jacqueline Durran borrowed different fashions from varying time periods to cloth the characters to evoke a sense of the past. This live action version of Disney’s classic Beauty and the Beast will be loved by current audiences, but future directors, playwrights, and actors will continue to interpret the timeless classic.

Don’t miss the fabulous new exhibit on styles from the 1600s through the 1800s at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. “Printed Fashions: Textiles for Clothing and Home” features more than 75 gowns, quilts, men’s waistcoats, curtains and more.

Guest Blogger: Neal Hurst

Neal Hurst is associate curator of costumes and textiles at Colonial Williamsburg. He earned his B.A. in history from the College of William and Mary and his M.A. from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture.

Neal Hurst is associate curator of costumes and textiles at Colonial Williamsburg. He earned his B.A. in history from the College of William and Mary and his M.A. from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture.

Silvia Helena says

This post is the best one about fashion history. Congratulations! ?

Silvia Helena says

Thais post os The best onde Abit fashion history. Congratulations!!!!!

This is a fun and educational look into the intersections of history, preservation, and pop culture. I hope Neil will guest blog more about period costuming portrayed in film, TV, and stage. CW has a wealth of specialists who can make these connections in other aspects of colonial culture, too.

If you’re talking about the roughness of a fabric, it’s spelled coarse instead of course.

Thank you for sharing!! Very interesting on the film version costume interpretation versus period really!!

What an interesting article! Having just seen the movie, it really makes the costuming come to life.