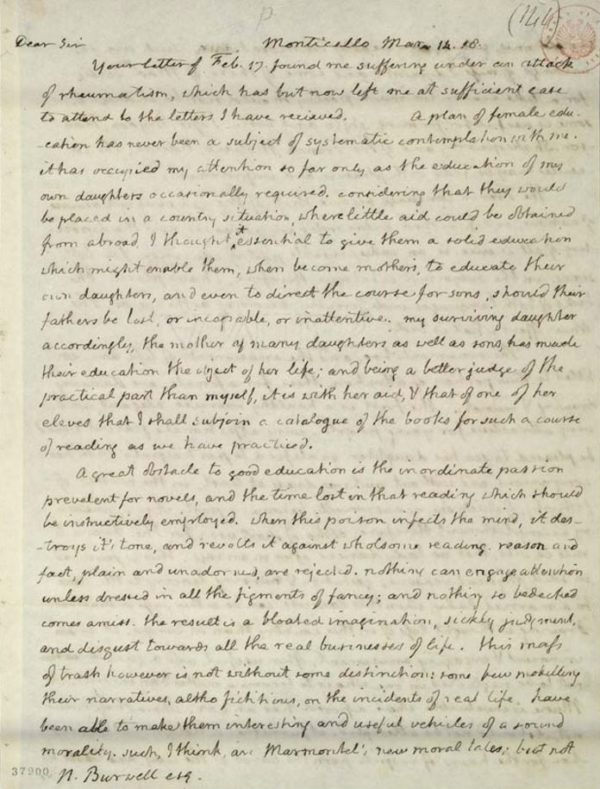

On March 14, 1818, 74-year old Thomas Jefferson put quill to paper to answer a query from Nathaniel Burwell: his thoughts on how to give a young woman “a liberal and accomplished education.”

The two-page letter he sent from Monticello is, quite simply intriguing. For many contemporary readers it may be troubling. Here, his erudition and enthusiasm for classical learning is blended with strong opinions and a view of women that was perhaps already behind the times.

The man whose voluminous writings show how thoroughly he tended to approach every issue or problem admitted that female education had “never been a subject of systematic contemplation with me.”

Of course, he did ensure that his daughter Martha received an enviable education, but it had a specific purpose. Since he envisioned a rural life for his family (“a country situation,” he called it), it would be necessary to “enable them, when become mothers, to educate their own daughters, and even to direct the course for sons, should their fathers be lost, or incapable, or inattentive.”

With Martha’s help he assembled a reading list for a woman’s education, which included a grammar, a dictionary, Pike’s Arithmetic, Pinkerton’s Geography, Buffon’s Natural History (in French), and Thomas Whateley’s treatise on gardening.

And numerous histories: of Greece and Rome, England and France, even a history of the American Revolution by Carlo Botta, an Italian.

While Shakespeare and other dramatic works made the cut, Jefferson was definitely no fan of the beach read, condemning the “inordinate passion prevalent for novels” as a “mass of trash” and “a great obstacle” to a good education:

When this poison infects the mind, it destroys its tone and revolts it against wholesome reading. Reason and fact, plain and unadorned, are rejected. Nothing can engage attention unless dressed in all the figments of fancy, and nothing so bedecked comes amiss. The result is a bloated imagination, sickly judgment, and disgust towards all the real businesses of life.

One can only imagine how he might feel about being a character in countless novels over the years.

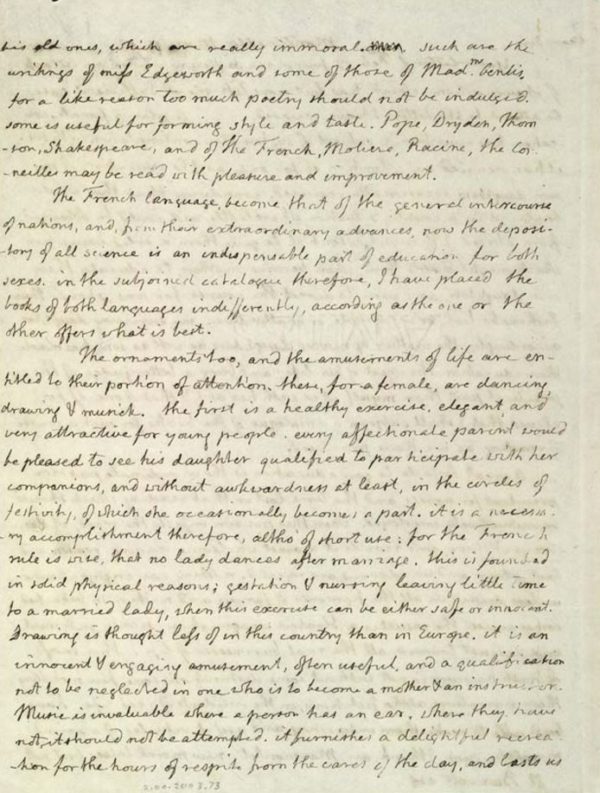

Still, Jefferson acknowledged that the “ornaments” and “amusements” of life, specifically dancing, drawing, and music, had their place. To a point.

Dance, he wrote, “is a healthy exercise, elegant and very attractive for young people. Every affectionate parent would be pleased to see his daughter qualified to participate with her companions, and without awkwardness at least, in the circles of festivity, of which she occasionally becomes a part.”

But…

The skill was “of short use, for the French rule is wise, that no lady dances after marriage.” Why? Well, for “solid physical reasons, gestation and nursing leaving little time to a married lady when this exercise can be either safe or innocent.”

Drawing was “an innocent and engaging amusement,” though of more use in Europe, where the skill was better appreciated.

The violinist Jefferson clearly favored learning an instrument over other pastimes. It provided “delightful recreation for the hours of respite from the cares of the day.”

But…

Only if you had some talent. “Where they have not [an ear for music], it should not be attempted.”

Jefferson’s letter is only one small piece of evidence about his attitudes about education and women’s roles in the early 19th century. If nothing else, it’s a healthy reminder that we are pretty selective in choosing when to quote the founders. They were, after all, flawed like all of us. There are many high ideals we still embrace, but also perspectives that we’d just as soon leave behind.

Interesting and probably not with the times even then. We do know that George Washington was said to be an accomplished dancer and I believe he probably danced with married ladies. Seems like TJ was “old fashioned “to say the least..