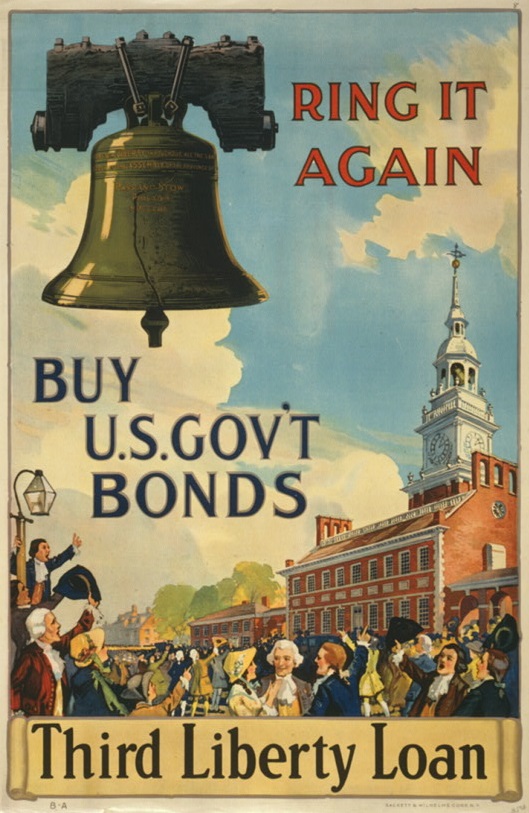

You can know what a community values by its bells. In Williamsburg we have bells at the Capitol, at Bruton Parish Church, and at the Market House. This year the First Baptist Church renewed the Let Freedom Ring Challenge, inviting people from all walks of life to take a turn at the cord and ring their historic bell, to inspire us to keep working towards freedom and equality for all. With that in mind, we present this excerpt from “Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly,” relating the surprising story of the Liberty Bell’s origin and evolution as a symbol for our aspirations as a people.

There is no evidence that the Liberty Bell rang on July 4, 1776. Indeed, there’s no evidence the Declaration was read to the public until July 8. Even then, though contemporary reports of the reading mention the ringing of bells, none specified the bell in the Pennsylvania State House. By the late nineteenth century, however, hardly anyone doubted that the Liberty Bell rang for the Declaration of Independence.

As a symbol of American liberty, the State House bell was in one sense a strange choice, since it was originally cast at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in London. (The bells in the Market House and Bruton Parish Church were also made by Whitechapel.) The Pennsylvania Assembly ordered the bell in 1751, well before the Revolution. The inscription on the bell came from Leviticus and was probably meant to honor Pennsylvania’s charter: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

Whitechapel Bell Foundry. Photo by Stephen Craven.

The bell rang for many important events, among them King George III’s 1760 ascension to the throne, the 1764 repeal of the Sugar Act, the 1775 Battle of Lexington and Concord, and—just maybe—the July 8, 1776, reading of the Declaration. It rang so often that in 1772 neighbors sent the Assembly a petition complaining that “they are much incommoded and distressed by the too frequent ringing of the great bell in the steeple of the state-house, the inconvenience of which has been often felt severely when some of the petitioners families have been afflicted with sickness, at which times, from its uncommon size and unusual sound, it is extremely dangerous, and may prove fatal.”

In 1777, as the British army approached Philadelphia, citizens spirited away the bell, hiding it in the basement of a church in Allentown. The bell returned to Philadelphia the next year and later tolled for, among other events, the ratification of the Constitution and the deaths of George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson.

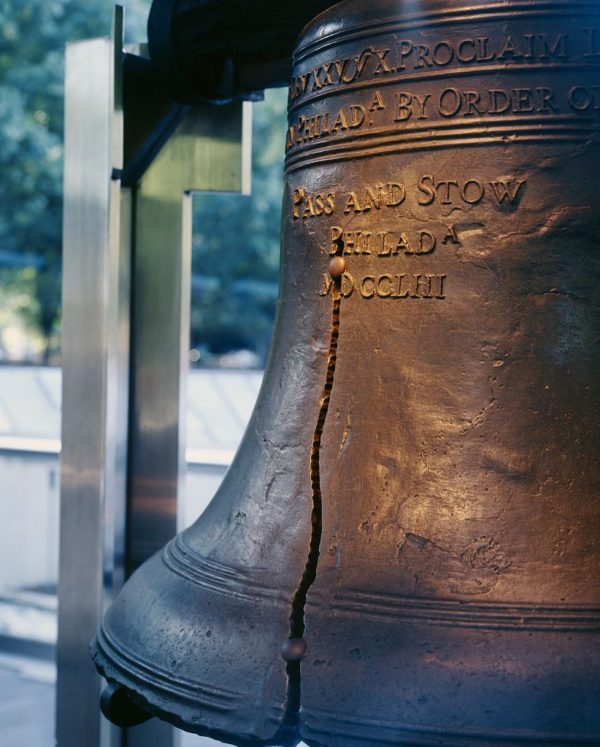

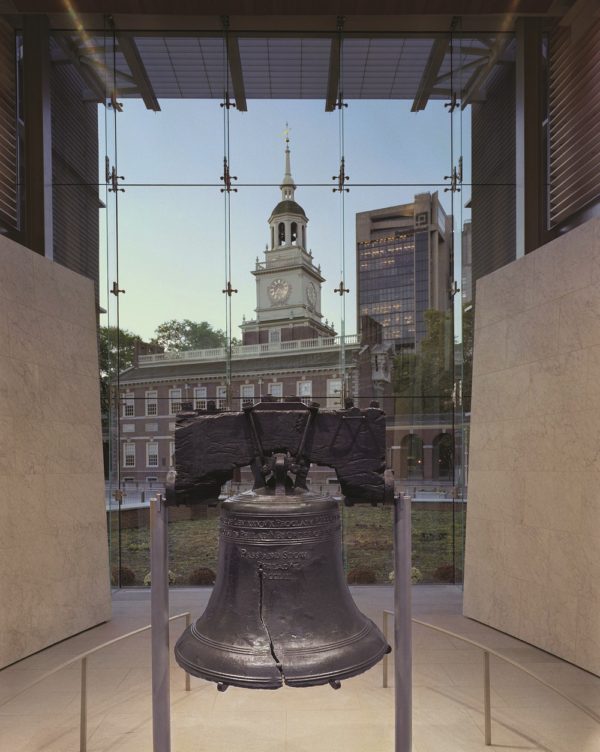

The cracked Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

During one of the events for which the bell tolled—exactly which has been the subject of much controversy—the bell cracked. Some reports date the crack to 1824 when it rang for the marquis de Lafayette’s visit to Philadelphia. Others blame an 1828 celebration of a British Parliament decision easing discrimination against Catholics. The most common date given for the crack, though with no evidence from contemporary sources, is 1835, when it rang for the death of Chief Justice John Marshall.

According to Emmanuel Rauch, who recalled the events of 1835 in 1911 when he was 86 years old, he and several other boys cracked the bell. The boys, including the then-ten-year-old Rauch, had the honor of ringing in Washington’s birthday. Rauch told the New York Times: “We were working away, and the bell had struck, so far as I can recall, about ten or a dozen times, when we noticed a change in the tone. We kept on ringing… but, after a while, the steeplekeeper noticed the difference, too. Surmising that something might be wrong, he told us to stop pulling the rope.” The steeple keeper then told the boys to go home, which they did.

The Liberty Bell was displayed at the World’s Fair in St. Louis in 1904.

Most likely, the bell’s problems dated back to well before Rauch and his friends were born. In 1753, after the bell was first hung in the State House, Isaac Norris, who had signed the Assembly’s letter ordering the bell, noted: “I had the mortification to hear that it was cracked by the stroke of the clapper without any other viollence as it was hung up to try the sound.” Two Philadelphia foundry workers twice melted down and recast the bell, but Norris was still displeased with the results.

The two recastings probably weakened the bell, making it susceptible to cracks. In any case, in 1846 the crack expanded to an extent that it ruined the bell’s sound and led its keepers to fear it would fracture further. Recorded the Philadelphia Public Ledger of February 26: “The old Independence Bell. . . . rang its last clear note on Monday last, in honor of the birth day of Washington, and now hangs in the great city steeple irreparably cracked and forever dumb.”

London’s Whitechapel Bell Foundry, which recently announced it is closing its doors after over 400 years in business, has long defended its craftsmanship. Whitechapel’s website noted that, if a bell is struck and not allowed to ring freely, because either the clapper or some part of the frame or fittings are in contact with the bell, then a crack can easily develop. The website also recounted that during the American bicentennial some mock protesters marched outside the foundry with signs proclaiming “We Got a Lemon” and “What about the Warranty?” The company responded that it would be happy to replace the bell—as long as it was returned in its original packaging.

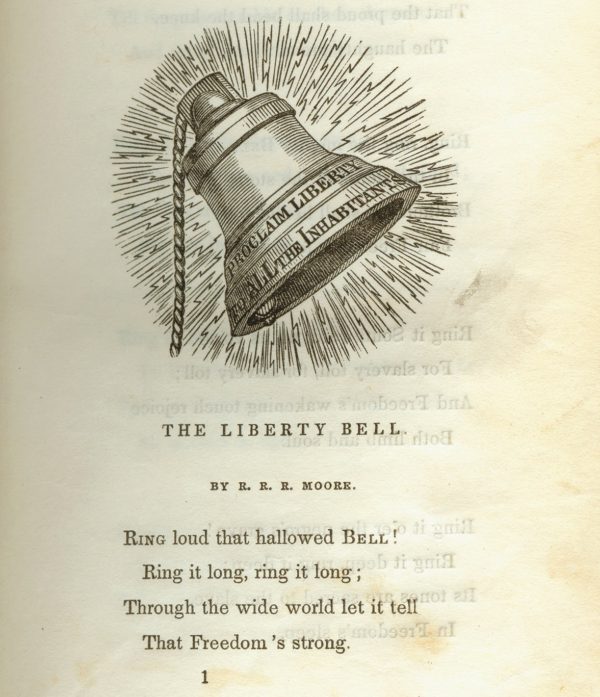

First page of “The Liberty Bell,” from The Liberty Bell, published by the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Fair, Boston, 1844. Courtesy Independence National Historical Park.

Back in the 19th century, the crack was not entirely inappropriate for a symbol of liberty in a land that still allowed slavery, and abolitionists adopted it as their own symbol. The first documented use of the name “Liberty Bell” came in the 1835 edition of the American Anti-Slavery Society’s Anti-Slavery Record. (Before then, it was usually called the “State House bell.”) In Boston, William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, published a poem titled “The Liberty Bell” in 1839. Another group of Boston abolitionists titled their publication The Liberty Bell and often featured poems about and illustrations of the bell.

Liberty Bell for suffrage. Harris and Ewing Collection, Library of Congress.

Later, women’s suffragists used the Liberty Bell, sending around the country a full-size replica. They did not ring their bell until 1920 when women won the right to vote.

This being America, the Liberty Bell also has been used to promote products and services. It has appeared in ads for, among others, banks, foods, stores, and railroads. “The Liberty Bell sounded freedom from a foe,” proclaimed a 1915 ad for flour in a Salt Lake City newspaper. “The women of this region have been freed from the worries of poor bread by White Fawn Flour.” In 1996, in full-page ads in newspapers throughout the country, Taco Bell announced it had purchased the bell and renamed it the “Taco Liberty Bell.” This went a bit far for outraged Americans, and the company quickly issued a press release explaining that the ads were an April Fools’ Day joke.

The Liberty Bell in the Liberty Bell Center. Courtesy Independence National Historical Park.

More seriously contentious were the plans, begun in the 1990s, for a new home for the bell in a pavilion to be built a block from Independence Hall. Should the bell be treated primarily as a symbol of the liberty achieved in 1776? Or should more emphasis be placed on the bell’s role as an inspiration for those, in particular African Americans, whose liberty was denied? Even the site raised issues. Here had stood a mansion in which George Washington had lived when Philadelphia was the nation’s capital—and with Washington had come enslaved African Americans from Mount Vernon. The new Liberty Bell Center, opened in 2003, showcases the bell’s role in the abolitionist, women’s suffrage, and civil rights movements. Concluded historian Gary Nash: “Now it is truly everyone’s bell.”

GUEST BLOGGER: Paul Aron

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly and several other books celebrating American history, including most recently Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

I was curious if you ever considered changing the

layout of your site? Its very well written; I love what youve got

to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better.

Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or 2 pictures.

Maybe you could space it out better?

Harriet Tubman is an American heroine, but her life story is shrouded in myth and exaggeration. Thanks to the work of Maxwell faculty members and students, the genuine contributions of Tubman’s life are coming to light.