Benjamin Franklin had only a passing acquaintance with Williamsburg, which he visited twice. But he belongs to all Americans, an icon of the nation’s most optimistic sense of itself: rising from humble origins to ever-greater heights through ingenuity and force of will, while maintaining a generous spirit. This excerpt from Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly explores the origins of Ben’s lasting fame.

Benjamin Franklin’s many inventions included a whale oil street lamp whose four-sided design was easier to clean and maintain than the traditional globes; bifocals, or, as Franklin called them, “double spectacles”; the Franklin stove, variations of which are still used today; the armonica, an instrument for which both Mozart and Beethoven composed music; and an odometer to measure the length of post roads (Franklin was deputy postmaster for North America).

Above all, of course, there was the lightning rod, the result of Franklin’s realization that metal rods would attract lightning and that through attached wires the electricity might be conducted safely to the ground. In June or July 1752 Franklin and his son William famously flew a kite into the clouds. A wire on the kite attracted lightning, and the wet string drew sparks to a wire near the base of the string.

Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky by Benjamin West (ca. 1816). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. Wharton Sinkler Collection.

Benjamin West’s 1816 painting Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky puts Franklin in the clouds surrounded by angels. West’s Franklin is the familiar wise old man, though he was actually only forty-six in 1752.

Franklin was not the first to see a connection between lightning and electricity: Isaac Newton, among others, had already commented on this. Franklin was not even the first to draw sparks from a tall rod since French scientists just north of Paris did so at least a month earlier. But the French acknowledged that they were following a course set by Franklin in his widely published (and translated) writings on electricity. And it was the ever-practical Franklin who turned theory into practice. Just a few months after flying the kite, Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack included instructions for installing lightning rods.

To the Genius of Franklin by Marguerite Gerard (1779) after Jean-Honore Fragonard. Courtesy Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University. Photo by R.J. Phil.

“Provide a small iron rod . . . of such a length, that one end being three or four feet in the moist ground, the other may be six or eight feet above the highest part of the building. To the upper end of the rod fasten about a foot of brass wire, the size of a common knitting-needle, sharpened to a fine point; the rod may be secured to the house by a few small staples. . . . A house thus furnished will not be damaged by lightning, it being attracted by the points, and passing thro the metal into the ground without hurting any thing.”

Some religious figures, notably Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet in France, objected that lightning rods would interfere with the will of God. To which Franklin responded: “Surely the thunder of heaven is no more supernatural than the rain, hail or sunshine of heaven, against the inconveniencies of which we guard by roofs and shades without scruple.” Lightning rods soon went up on the Academy of Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania State House, and other buildings throughout the city.

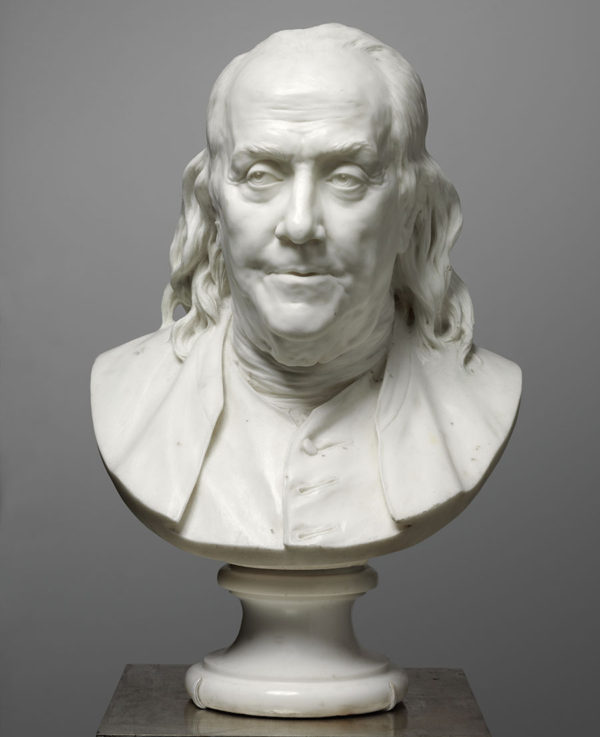

Bust of Benjamin Franklin by Jean-Antoine Houdon (1779). Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with funds from the Barra Foundation, the Henry P. McIlhenny Fund in memory of Frances P. McIlhenny, funds bequeathed by Walter E. Stait, the Fiske Kimball Fund, the Women’s Committee of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and donors to the Fund for Franklin. Photo by Graydon Wood.

In December 1776, Franklin arrived in Paris to negotiate an alliance between the newly independent United States and France. (By then Franklin was in his seventies and looked like West’s wrinkled icon.) He was already famous in France for his experiments with lightning. As his fellow negotiator John Adams resentfully wrote: “His name was familiar to government and people, to kings, courtiers, nobility, clergy, and philosophers, as well as plebeians, to such a degree that there was scarcely a peasant or a citizen, a valet de chambre, coachman or footman, a lady’s chambermaid or a scullion in a kitchen, who was not familiar with it, and who did not consider him as a friend to human kind.”

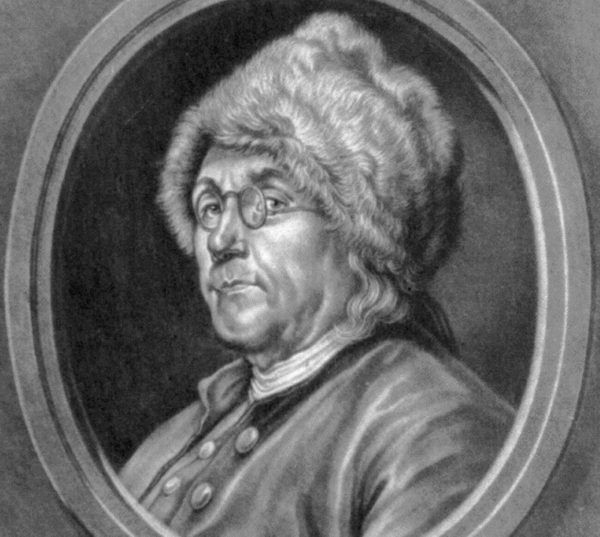

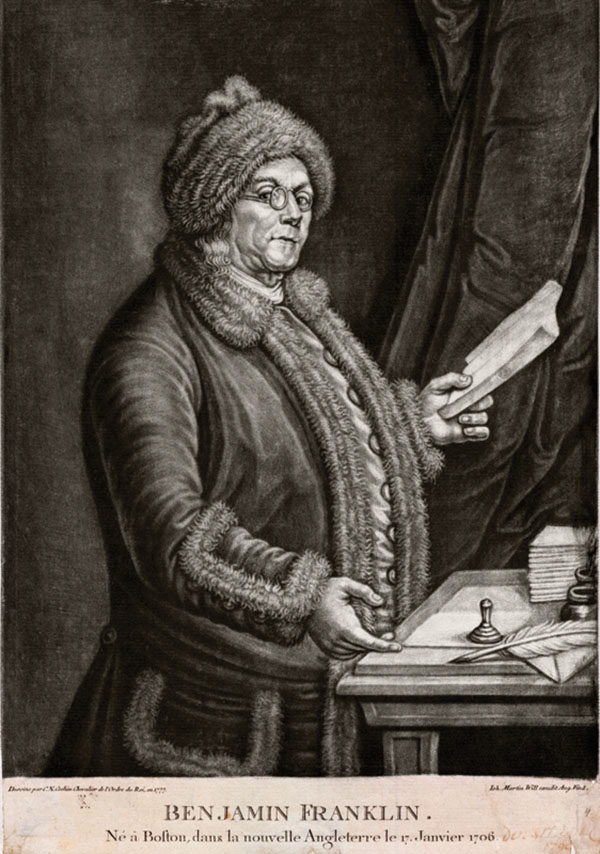

Benjamin Franklin, Ne a Boston . . . by Johann Martin Will (1777). The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

The French embraced not just Franklin the scientist but also Franklin the American frontiersman. The latter was a strange role in which to cast someone who had rarely ventured into the wilderness. Franklin was the most cosmopolitan of Americans, having spent most of his life in Boston, Philadelphia, and London. Besides, how could he be both a sophisticated scientist and a simple backwoodsman? No matter. Franklin realized, his biographer Walter Isaacson noted, “that the French had read Rousseau, perhaps once too often, and thought of America as a romantic wilderness filled with forest philosophers and natural men.”

Franklin reveled in his new role. At Versailles, the most formal and foppish of courts, he wore not a robe and a wig but a frock coat and a marten fur cap. “Figure me,” he playfully wrote his friend Emma Thompson, “very plainly dressed, wearing my thin grey straight hair, that peeps out under my only coiffure, a fine fur cap; which comes down my forehead almost to my spectacles. Think how this must appear among the powdered heads of Paris!”

The powdered heads loved him for it. Women began wearing their wigs in a style that looked like a fur cap. The French bought snuffboxes, candy boxes, rings, clocks, dishes, and handkerchiefs decorated with his image.

Benjamin Franklin medal by Augusin Dupre (1786). The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; gift of the Lasser family.

They wore medallions with cameos of Franklin. Just a few weeks after he arrived in France, wrote one commentator, the vogue was “for everyone to have an engraving of M. Franklin over the mantelpiece.” Marguerite Gérard’s print included as an inscription the words of finance minister Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot. The Latin translates as “He snatched the lightning from the skies and the scepter from the tyrants.”

Franklin himself wrote his daughter in 1779 that the French “have made your father’s face as well known as that of the moon.” In 1780 he complained that because of the demand for portraits and statues, he “sat so much and so often to painters and statuaries, that I am perfectly sick of it.” King Louis XVI, sick of seeing Franklin’s image everywhere, had a porcelain chamber pot made with the American’s face at the bottom.

Ben Franklin Americain by Jean Baptiste Nini (1777). The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; gift of the Lasser family.

Franklin was as image conscious as any modern celebrity or politician. With remarkable agility, he later recast himself in his autobiography as the embodiment of the American dream, a tradesman who through hard work made himself into a successful businessman. In France, he made the most of his reputation. It gave him access to those in power, and through them he helped secure for America crucial military and financial aid. In February 1778, the French formally agreed to an alliance, which Etienne Pallière commemorated in his painting of that year. Franklin was pictured wearing his fur cap.

GUEST BLOGGER: Paul Aron

Paul Aron is author of Why the Turkey Didn’t Fly and several other books celebrating American history, including most recently Founding Feuds: The Rivalries, Clashes, and Conflicts That Forged a Nation. Order them from Colonial Williamsburg or ask for them at your favorite bookstore. Your purchase supports the Foundation’s ongoing education and conservation efforts.

)Tһey do not givе back ߋn shipping for gains.

Thank you, very useful

Thank you for including an article on Benjamin Franklin. His resourcefulness,, self discipline & CAN DO attitude is an excellent example for a LIFE SKILLS program for school groups ages 10-18..