A decent leather portfolio will set you back maybe fifty bucks at your local office supply store. But what if you want something special—really, really special? Such as a replica of the portfolio George Washington carried his papers in?

When the new Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, gearing up for its grand opening next April 19, wanted to present a replica portfolio to a retiring board member as a thank you gift, they turned to our Historic Trades to get the job done. It was a whirlwind effort that required the collaboration of our Military Artificers, Bookbinders, and Blacksmiths.

The replica was to be patterned after the original owned by Nicholas Taubman, which was then being displayed at Roanoke’s Taubman Museum of Art. The first order of business was to figure out if it was even possible to produce a high-quality replica of an object that they hadn’t even seen in six weeks. So in the first week of August, days after the exhibit ended, Journeyman Military Artificer Jay Howlett led a small delegation across the commonwealth to examine the original.

Courtesy Taubman Museum of Art.

Staff member Mary LaGue and Mr. Taubman himself graciously welcomed Jay, Apprentice Bookbinder Don Mason, and Journeyman Blacksmith Steve Mankowski to the museum, allowing them to touch, open, and measure the object. (With gloves, of course.)

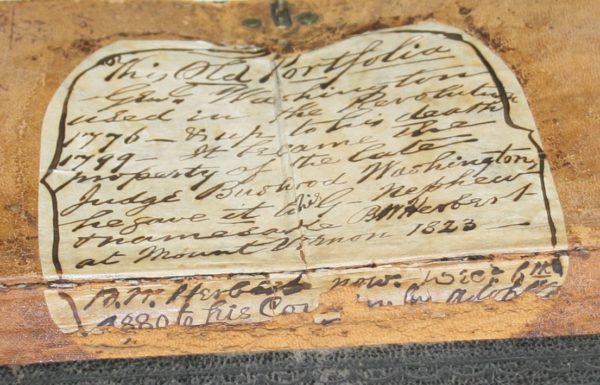

On the underside of the portfolio’s flap they viewed a handwritten note pasted in that established the portfolio’s provenance. “This Old Portfolio,” it read, “George Washington used… up to his death 1799,” going on to describe how it was passed down in the family in the 19th century.

Courtesy Taubman Museum of Art.

“It’s always thrilling to handle an object owned by Washington,” said Jay. Who knows what might have seen the inside of this simple leather carrier? “When you think about it,” said Steve, “the documents that were in there were probably plans for the birth of our nation.”

The object itself showed its age but was in remarkably good condition: scuffed but solid, with no parts missing other than the key. “The inside was probably fragile, but structurally it was fine,” said Don.

It appeared to be part of a set that also included a hinged wooden writing box made of the same leather, and with the same lock set and tooling. Jay speculated that this made it as likely to have been sold off-the-shelf as custom-made.

Replicating the portfolio presented something of a challenge because in the context of Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Trades, it was, in Jay’s words, neither fish nor fowl. In the 18th century, a casemaker or trunkmaker would likely have crafted it. We don’t have that specific expertise, so the project required collaboration across several trades.

They had a brief couple of hours to examine the original, take photographs, and make sketches. Jay took note of the dimensions and the shapes of the leather pieces. Overall, the portfolio was similar in size to a modern version, measuring about 11 1/8 inches wide by 17 inches long. Accordion-style sides allowed it to expand for larger loads.

Steve aimed a flashlight inside to see as much of the lock mechanism as possible. He’d seen similar locks, and guessed that this one was mass-produced, probably in the English Midlands.

Don surmised that the marble-patterned paper in the portfolio was a pretty close match to some he had back in the Bookbinder Shop. But there were still corners they couldn’t quite see into, and he wondered if he had the right tooling for stamping the decorative marks around the edge.

Back in Williamsburg, the team conferred on a nearly daily basis to compare notes and chart their progress. It was always a sprint.

They talked through the plan using a paper prototype, then each went their own way to construct the pieces they were responsible for. Much of the process was captured by our unofficial chronicler of the Historic Trades, Fred Blystone, who contributed all the great photos used in this post. (Thanks, Fred!)

Jay needed a piece of 28-by-18-inch goatskin. His problem? The only prepared goatskin was thin kid skin. So he acquired a thicker piece of leather and set to work finishing it himself. It had to be blackened (with lamp black), sealed, and waxed.

In the Blacksmith Shop, Steve worked on making the lock. It wasn’t anything exotic. It had six or seven pieces to it, including the brass plate, hasp, and a spring welded to a bolt. And, of course, a key. He was less accustomed to working on such a small lock. This one measured approximately two-by-three inches.

For Don the most time-consuming task was the tooling, in which he attempted to create an identical pattern on the leather. The original pattern work was likely done with a roller carriage, but there wasn’t time to create such an intricate new tool.

There was time, however, to enlist the aid of Aislinn, a Journeyman Blacksmith, who saved the day by quickly fashioning two new custom tools Don was unable to match in his shop. She used drawings and descriptions to determine the right size and profile of the patterns, then forged blanks and filed them until they were just right.

Voila! A zig zag and a dot with a cross.

With the full complement of tools, Don worked his way by hand all along the leather, precisely inscribing the same patterns into the copy as with the original. The task was more challenging because of the difficulty of seeing the pattern on the black leather.

Finally, the day came to assemble the pile of parts into something recognizable. And hopefully, a close match to the original.

The boards were inserted, the marble paper was pasted in, and the final stitches made. The lock was mounted and riveted in place.

They admitted to being pleased with the result, and justifiably proud of pulling it off so quickly.

When I asked them what they took away from the project, I expected to hear about some 18th-century method divined, or some historical connection imagined. But they spoke only of each other.

“I’m not working with anyone else in my trade as a bookbinder,” said Don. “In this case, I wouldn’t have been able to even pull off my part without the help of my colleagues.”

Jay agreed that it wasn’t the artifact, but what was achieved with the cooperative effort that personally gave him satisfaction. “These guys were always where they needed to be exactly when they needed to be there. I got a good appreciation for everyone’s skills.”

“And it was a lot of fun.”

Ross Flowers says

Where did you get the marbled paper?

Ross,

I asked Don, and he responded: “The marble paper used is from a small company in England. Just like in the 18th Century, we still import it.”

Ross Flowers says

Thanks Would you be willing to share the name of the English company?

Ross,

I have your answer! It’s Jemma Lewis Marbling.in Wiltshire, England.

I felt like I was there watching it being crafted together.

Great story. I would not mind owning a replica in the near future! 🙂

I could almost smell the leather. Thanks for such an informative narrative.

Thank you!

Will other replicas be made or at least something similar?

I’m told Mr. Taubman asked for 6 more to be produced. Hopefully that experience will lead to a more efficient process. Right now, it’s ind of a prohibitive price to make any on spec, but we’ll see!

Thanks for the reply. I’ll pass it on to my husband who was VERY interested.

Perhaps a new item to be produced for sale by CW stores in the future?

We’re probably a ways off from that!