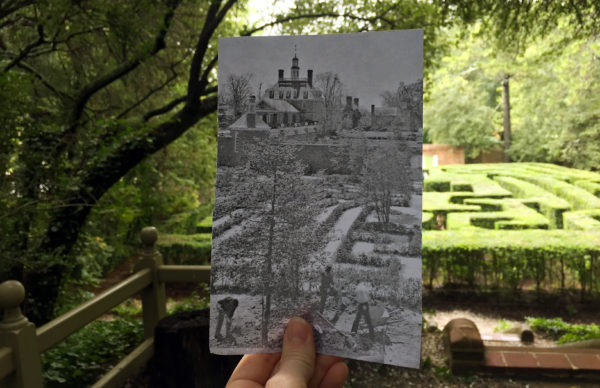

The Governor’s Palace maze, 1935 & 2016

The Governor’s Palace maze. It is a “must-see” when visiting Colonial Williamsburg, and millions have wound their way through its hedges since it opened in the 1930s. If you are a die-hard CW fan, chances are you’ve traipsed through it more than once. But what of its history? How it was created? What it takes to maintain it today? Lace up your sneakers, friends. Let’s walk through it together!

Garden mazes have a surprisingly long history—early examples date to the mid-15th-century—but it wasn’t until the 18th century they really exploded in popularity. When it became fashionable to have one, they started popping up all over Europe. For their owners, the mazes were status symbols that conveyed wealth (design, installation, and maintenance wasn’t cheap, after all) and offered a trendy way to amuse guests. Perhaps not that dissimilar to a Maserati or a house in the Hamptons today.

Although many were lost to time, some of these centuries-old mazes have survived to the present day. Il Labirinto (“the labyrinth”) at Villa Pisani in Italy offers a good example. Legend has it that Napoleon got lost in it around 1807, while Hitler and Mussolini decided they valued their reputations more than the challenge. When presented with the opportunity to try it during their meeting at the villa in 1934, they declined.

Yet, perhaps the most well-known maze is found at Hampton Court in London, and if you’ve explored (or in the case of this author, found yourself hopelessly lost within) it, you’ve seen a source of inspiration for the one behind the Governor’s Palace.

Hampton Court Palace

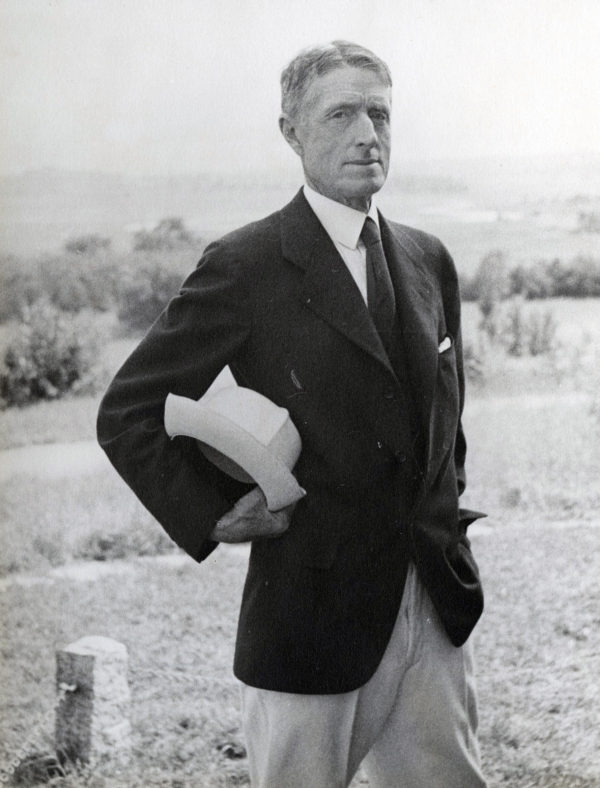

The Colonial Williamsburg maze, like much of the restored and reconstructed gardens, was the brainchild of the Foundation’s first landscape architect, Arthur A. Shurcliff. Overstating Shurcliff’s credentials would be difficult. He earned an engineering degree at M.I.T.; studied history, design, and horticulture at Harvard; and began his career working for the “father of landscape architecture,” Frederick Law Olmsted. It would be equally difficult to overstate his importance in Colonial Williamsburg history. He designed and oversaw the creation and restoration of CW’s gardens and green spaces, and in the process, left an indelible mark on the Historic Area that is still felt today.

Arthur A. Shurcliff, c. 1930 (Colonial Williamsburg Corporate Archives)

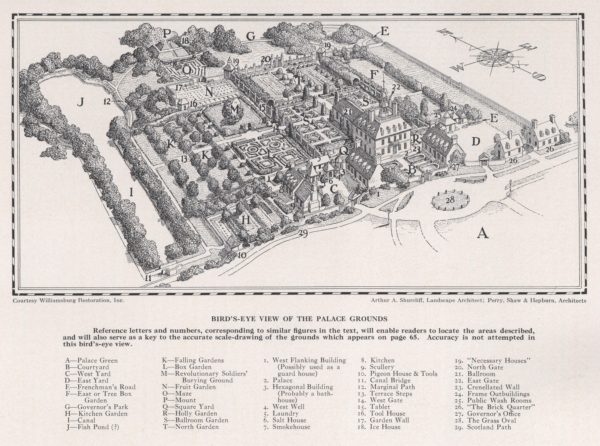

For all of Schurcliff’s designs, he utilized what evidence could be found concerning Williamsburg—diaries, ledgers, maps, letters, drawings, records, archaeology—and made a meticulous study of larger 18th-century designs and styles, both in America and Europe. Indeed, he visited dozens of estates and gardens to understand the time period and its aesthetic. He applied the same detective work to the maze. No evidence could be found of a maze behind the Governor’s Palace in the 18th century, but there was a “mount.” Mounts were essentially ice houses, built into the earth and lined with brick to offer insulation for preserving food and ice during summer months. They were often placed in gardens, and the small hill that they created offered an elevated view. As a result, mazes were often planted below them. This turned the mount into an overlook where owners could watch guests as they worked their way through the maze, which must have been quite a source of entertainment.

As he explained in a piece written for the trade periodical Landscape Architecture in 1937, “a pleasure place designed for entertainment of a more boisterous kind seemed probable” in this space. “Remembering English precedents and the Mounts which in England are often associated with a maze,” he continued, “the idea occurred that a maze would be appropriate here.”

Birds-Eye View of the Palace (Landscape Architecture, 1937)

One aspect of Colonial Williamsburg’s founding that should never cease to amaze is the tremendous amount of research conducted for even the smallest of details. The wooden railing at the top of the mount, for example, can seem simply practical. Yet it is actually a copy of the mount at New College, Oxford, and Schurcliff was able to replicate it because he traveled to England to examine old drawings and measure it himself.

Governor’s Palace maze and railing, n.d.

That said, creating the maze was not without its challenges. As Schurcliff noted in Landscape Architecture, they learned—assumedly the hard way—that trying to plant holly hedges in soil that was not fully drained was futile, and that plants whose roots were exposed to cold weather while in transit would die.

Governor’s Palace Maze, 1935.

That wasn’t the last time the maze encountered difficulties, either. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the tremendous usage—upwards of 1,000 people a day during the high season—began to take its toll. In 1981, the maze was so frail that the Foundation closed it for three years. They pruned the once eight-foot-tall hedge down to 18 inches, replaced dozens of the hollies, and nurtured the plants until the maze was sturdy enough to reopen.

Luckily, the maze rebounded, and this dedication to its preservation is still alive and well. To learn more about how it is maintained today, we went straight to the source: the Palace Landscape Crew. Foreman Michael Johnson explained that his team does basic maintenance once or twice a week, consisting mostly of keeping weeds at bay and looking for anything that needs repair. The far bigger task is trimming the entire maze. That happens about five times a year—usually around major holidays—and takes a crew of six workers, using ladders and gas-powered shears, three hours to complete. Interestingly, those power tools are a relatively recent addition. Wardell Frazier has worked for Colonial Williamsburg since 1979, and remembers doing everything by hand through the late 1980s. “We didn’t trim as often back then, but it took a long time to do by hand,” Mr. Frazier said. “Switching to gas equipment helped a lot, because it moved things along a lot faster.”

The Palace Landscape Crew estimates that a few hundred people now go through the maze each day, but say it isn’t foot traffic that creates the biggest strain. What’s the biggest challenge, then? Cheaters. “The maze would do even better if people didn’t cut through the hedges to make shortcuts for themselves,” Mr. Frazier said. “The rule is,” Mr. Johnson added, “if you can’t see over the hedge, you shouldn’t be going through it.”

Although it isn’t pint-sized users like this young fellow who need a gentle reminder from time to time. “You’d be surprised to know that the biggest offenders aren’t kids, they’re usually adults,” Mr. Frazier admitted. “They get into the maze, get a little stir crazy, and decide to create their own way out. That creates holes, and makes the hedges look less full. If you could stop that, you’d be in good shape. But we keep it looking sharp regardless.”

So you heard it here first, folks:

When did you first explore our maze? Let us know in the comments. Bonus points for any photographs of your adventure!

- Governor’s Palace maze, 1947.

- Governor’s Palace maze, 1946.

- Governor’s Palace maze, 1969.

- Governor’s Palace maze, 1970.

- Governor’s Palace maze, 2014.

Special thanks to Michael Johnson, Wardell Frazier, and Scott Cochran for taking time out of their workday to discuss the maze, and the entire CW maintenance crew for their dedication to preserving the Historic Area.

My husband and I went on our first date-that-wasn’t-a-date (we were just friends at that point…) to Colonial Williamsburg. I had been a number of times before, but he hadn’t. It rained the whole time we were there, which gave me an excuse to get close to him under the umbrella. Despite the rain, we adventured through the maze. We had a blast and laughed the whole time. Two and a half years later, he took me back to the maze. When we made it to the center, he got down on one knee and proposed. It was absolutely perfect.

Needless to say, the maze holds a very special place in our hearts.

My first visit to the maze was some time in the 1970s; although I have visited the foundation before that .

i recall being saddened by the people breaking holes in the hedge just because they were in too much of a hurry to figure a way out. they are supposed to be on vacation after all.

Ted Miles, foundation member since the 1980s

It is good to see that the maze is being maintained.

I saw ‘cheaters’ and the damage they did and was afraid the maze would have to be removed.

My first trip of many was in 1964.

Is the maze wheelchair accessible?

From our third trip to CW in 1979. I cannot find any pictures of the maze earlier than this

Thank you for another history lesson; The Maze! I remember ALL too clearly; by first encounter with the Maze was in April, 1966., my first trip to Colonial Williamsburg. I “made it out” without cheating, but only with the help of adults cheering me on to turn right, left, left, right.

Probably did the maze the first time back in the 70’s. Always a fun thing to do! My sons have always loved going through and probably still have it memorized today, although the last time either went through was probably back in the 90’s! It’s fairly easy, once you get the hang of it, so not to worry about getting lost. I’ve always been upset by the cheaters too! 🙁

We’ve been to Colonial Williamsburg only three times, but the maze? Not. I know I’d get lost. The Maze is beautiful to look at though and I admire those who walk through it without a care about getting lost.

I cannot wait to visit Coloinal Williamsburg and take a try at this maze! Looks fun and kudos to the staff for keeping it so immaculate!