If a visit to Colonial Williamsburg is a trip back in time, when exactly is that time? We use shorthand terms so often—18th century, Revolutionary City, colonial America—that it’s easy to collapse a complex era into a kind of moment. But the Historic Area is made up of many moments over many years, and so are the buildings.

Virtual Williamsburg, which has been building a digital version of the city for more than a decade, offers just such a moment. There, it is forever 2 p.m. on Wednesday, May 15, 1776, the day the Fifth Virginia Convention passed the resolution asking the Continental Congress to declare independence. Even the shadows slanting into the street under a bright sun tell you this is a precise moment, not an amalgam of an entire period, in history.

It is an impressive resource available to the public, but it’s just as useful for Colonial Williamsburg’s own researchers who are constantly working to refine our understanding of the city. “It makes you think a lot harder and deeper than you do if you’re just simply writing about it,” says architectural historian Carl Lounsbury. “If you have to produce an image for it, you have to think it through and come up with reasons for why it looks the way it does.”

We’ll get to some of the most interesting differences you will find between the bricks-and-mortar structures of 2016 and the virtual 1776. But first, there are a few things you should know when you visit Virtual Williamsburg.

It’s pretty straightforward to use. The top navigation shows the main options. You can “Explore in 3D,” which allows you to “walk” down Duke of Gloucester Street, or through the Raleigh Tavern or the Dickson Store (interpreted today as Charlton’s Coffeehouse). When you go to this page the first time, you’ll be asked to install Unity, a simple plug-in that makes it possible to wander down DoG Street at your own pace. Be forewarned, however, that it does not play nice with Chrome, so if that’s your usual browser, you’ll have to use an alternative like Firefox or Internet Explorer to enjoy the 3D portions. Most mobile devices will also have trouble with the 3D functionality.

The 2D representations should work on any device, however. Selecting “Revolutionary City” will take you to an overhead map of the eastern section of town, where you can click on any building in red to get more information, including some digital renderings, history, and interior views. The third choice, “Armoury,” shows the block the blacksmith shop is on. See #6 for more about that!

Now get started exploring and see what interests you the most-then let us know!

#1 There were two Capitols

It’s kind of an open secret that we have what some consider the “wrong” Capitol anchoring the east end of town. Wrong, in the sense that Colonial Williamsburg reconstructed the first Capitol building, which was completed in 1705 and burned in 1747. So while it’s definitely a colonial capitol, it’s not the one that stood during the Revolution.

In 1753 a second capitol opened, with a more classical look. The rounded ends of the first capitol (which happen to be the basis for Colonial Williamsburg’s logo) are squared off, and the west-facing entrance shown here is much grander.

#2 There Are Unique Spaces to Explore

Virtual Williamsburg makes it possible to explore the differences in a variety of spaces, in and out of doors. The Capitol is one of those. Today we’re accustomed to seeing a kind of open breezeway that runs between the two wings in the reconstructed first Capitol. But in the second Capitol that space was enclosed, and its centerpiece was the statue of Lord Botetourt, who served as Virginia’s governor from 1768-70.

Today a replica of the statue stands in front of the Wren building, and the original is on the ground floor of Swem Library at the College of William & Mary. Cindy Decker, who does all the renderings for Virtual Williamsburg, expertly used a 1796 sketch by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, to create this scene.

#3 The Old Theater was really cool

Behind the Capitol you can find the Old Theater, a wonderful building that hasn’t existed in a very long time. You can explore it in a great deal of detail. To get there, enter 3D Williamsburg, then walk around the right side of the Capitol. The theater will be straight ahead. When you approach the door, a green button appears. Click on it and you will enter the theater.

You’re actually jumping back a little more in time here. With the war raging, Congress called for an end to frivolities like the entertainment that would have been staged here. The theater was closed, and would have likely been boarded up, in 1776, so the rendering shows how it would have looked in 1772.

Inside it looks close to showtime. Go upstairs and see what the stage looked like from one of the boxes. Look at the sets hanging below from the catwalk.

#4 Building Uses Changed Over Time

Charlton’s Coffeehouse was rebuilt just a few years ago, but did you know that it was actually the site of Dickson’s Store by 1776? In Virtual Williamsburg you can head right into the store and poke around. You’ll notice that instead of the tables where patrons could take their ease, there is a counter, and an assortment of wares for sale.

This is far from unusual. Many of the properties in town were businesses, and some seemed to turn over annually.

#5 It’s a Different Streetscape

Aside from slaloming around the deposits made by our horses, it’s pretty easy to walk through town today. The pavement is even and relatively flat. Virtual Williamsburg uses topographical maps to create an accurate terrain. So when you walk along virtual DoG Street, you immediately sense the rise and fall—okay, the ruts, divots, and bumps—of an 18th-century road. And no trees. It’s a reminder that just getting around without looking like you’d been in an accident was a lot more challenging then.

#6 Change Was a Constant

18th-century Williamsburg was a city in flux. Buildings were built, modified, and sometimes burned. Residents and businesses moved as frequently as they do today. So when you’re looking next to the King’s Arms Tavern, you’ll see a smallish building with only the frame completed. The Barbershop (which we know as the Wigmaker Shop) was in the middle of being built in 1776, and that is how it’s shown.

#7 We Still Have Some Holes to Fill

Wetherburn’s Tavern is called Robert Anderson’s Tavern in Virtual Williamsburg, because that’s who ran it in 1776. Like the Raleigh Tavern down the street, it had a porch. Recent archaeological work has shown that it extended all the way across the front of the building, so here is an example where Virtual Williamsburg led the way with a speculative image of a porch that turned out to be an incomplete rendering.

Visible on either side of Wetherburn’s are two shops known to have existed that have not, yet at least been rebuilt. On the left as you face the tavern is the Rowsay Jewelers’ Shop. On the right is the Virginia Gazette Shop, where Alexander Purdie was the first in town to print the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Perhaps the site will yield new evidence of life in Williamsburg, and down the road, perhaps they will be rebuilt.

#8 Williamsburg Really Was a City

Sometimes ongoing research makes us reevaluate what a building looked like in the 18th century. The current Raleigh Tavern porch project is an obvious example. But once in a while, we’re not really sure why a building was reconstructed in a particular way.

That’s the story with the Brick House Tavern, which stands at the southwest corner of DoG Street and Botetourt and is used as one of our Colonial Houses. A 1931 design for the reconstruction based on documentary evidence, especially insurance plans, had two stories. But for reasons we can only speculate about, it was built with a single story.

So why does this matter? Well, as Carl Lounsbury put is, “It’s a two-story rowhouse with six units. This makes Williamsburg very urban.” In other words, our quaint little village was taking definite steps to becoming a real city. Events stifled that momentum soon enough, but the reconstruction doesn’t fully reflect that reality.

#9 The Revolution Changed the Town

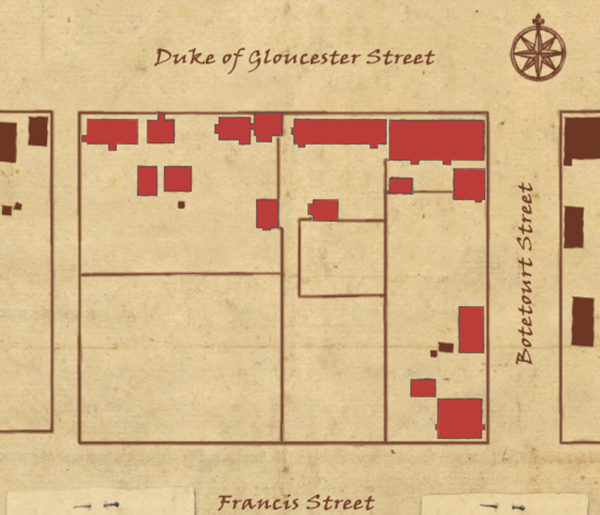

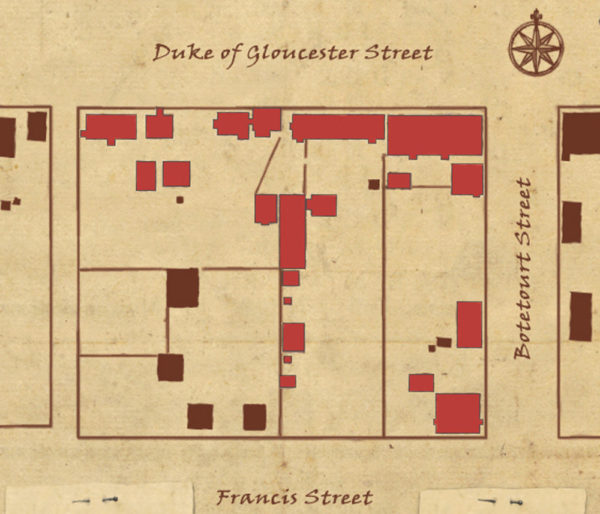

- James Anderson’s blacksmith business in 1776 . . .

- expanded to become the Public Armoury complex by 1779.

The onset of war altered the course of many lives, and it also altered the landscape. Select “Armoury” from the main screen of Virtual Williamsburg to see how one neighborhood changed. In 1776 James Anderson had a nice little blacksmith business behind his house at the former of Francis and Botetourt. In a few short years, the space became a complex of buildings housing work that contributed to the war effort.

On Virtual Williamsburg, you can toggle between interactive maps of this block from 1775 and 1779 and learn more about how wartime mobilization transformed the space.

#10 There Are Hidden Treasures

The walking tour down Duke of Gloucester Street on Virtual Williamsburg currently ends near the intersection of Botetourt Street. Like the city itself, it’s still under construction. But views of the Market House in its period setting were prepared during its recent reconstruction, helping everyone involved in the project visualize it and tweak the details. They haven’t made it onto the main Virtual Williamsburg page yet, but you can see several in this blog post.

We aren’t allowed to hang raw meat from hooks there today, but this view shows what it might have looked like.

Now look more closely. Behind the market is one of the most magnificent houses of 18th-century Williamsburg, Tazewell Hall. The 99-acre estate, known for its beautiful gardens, was the home of Peyton Randolph’s Loyalist brother, John “the Tory.” John and his family closed up the house in 1775 and–let’s say fled—to England, never to return.

A few years later, John Tazewell bought the vacant house, which is how it came to be known as Tazewell Hall. In 1908, the entire house was pivoted 90 degrees to accommodate the extension of England Street When the reconstruction began, it never really fit in. As the home of a loyalist, it wasn’t valued in quite the same way as other sites. So in the 1950s the structure was dismantled and sold to a private owner in Newport News.

Even in the 1700s, Williamsburg was a living, breathing place—always changing and evolving. And it’s worth mentioning that it didn’t stop evolving when the state capital moved to Richmond in 1780. So take a walk in our virtual world, and tell us what your favorite place is.

THANKS TO SCOTT TO A FINE PRESENTATION TO ONE OF THE JEWELS OF VIRGINIA……….NEVER TIRE OF OUR COLONIAL CAPITOL…..AND THANKS TO THE ROCKEFELLERS FOR SAVING THIS LITTLE BIT OF HISTORY………….I HAVE VISITED OFTEN, AND NEVER TIRE OF ITS DEPTH OF HISTORY, AND INCREDIBLE SIGHTS…………..VISIT A PLACE THAT LUCKILY FOR US, STILL EXISTS……………………

So interesting. I love this. Thanks for sharing. 🙂 I loved going to Williamsburg as a child and I can’t wait to go on the virtual tour.

I had learned about Tasewell Hall a few years ago. Had always wondered the reasons such a fine home had not been restored. I really do think it is a travesty/tragedy.

Thanks for the honesty on Tazewell Hall! I had heard everything from Rockefeller did not want the home of a Loyalist to it was beyond restoration. But since it was, in fact, moved and restored, the second reason obviously did not hold water!

It amazes me that Williamsburg looked so - well, RAW! Really, there were no trees even in the backs of houses on DoG Street? I’m guessing that the abundance of lovely gardens is also not accurate?

Pam,

On the trees, there’s this article on the website that you might find interesting: https://www.history.org/history/CWLand/resrch5.cfm

I consulted with our wonderful architectural historian Carl Lounsbury about the garden question, and he said:

“Yes, we have too many pocket gardens on side lots that seem highly unlikely. Few would have been exposed to public view along the street and certainly not surrounded by low paled fences. So there are too many ornamental gardens and not enough work yards. That is not to say however, that there were not any ornamental parterres, etc., only that they were fewer in number and generally associated with the gentry, not the working class artisans.”

I don’t believe Chrome allows plug-ins and so would require a WebGL build for it to run. Last I saw Firefox is ending plug-in support at the end of the year and will probably also require a WebGL build at that point. Unity just came out with a new version of their engine, 5.4, with better WebGL support but I gather converting between platforms, in this case WebPlayer to WebGL, never seem to go as smoothly as you’d like but I hope it does for their developers. Then again older versions of Explorer will still need the WebPlayer version so it’s all a balancing act. It took me a while to get it to load under Firefox but I’m guessing their servers are probably busy with a lot of people wanting to try it out.

Once I have some more free time I really look forward to checking this out in more detail. Thanks to the developers for all the hard work they put into this.

Question: If, as an example, Wetherburn’s Tavern was Robert Anderson’s Tavern in 1776, why is this not the name that is displayed? Are there any other reasons why more things are not changed to what they were in 1776? Just curious, as I thought that is what CW was representing.

I can’t speak to this with a great deal of expertise, but CW has portrayed many different years. I’m not sure there’s ever been an effort to interpret that narrowly because there would so much we couldn’t talk about. The Revolutionary City, for example, spanned 1774-81. The Armoury complex is 1779. Charlton’s Coffeehouse was in business in 1765, I believe, when the Stamp Act was passed. Some original buildings were not built until later. So it’s a balancing act among various interests: preserving the 18th century buildings, reflecting their most significant uses, and interpreting the Revolution.

Just discovered this blog and I am really enjoying reading all the previous blog entries. and learning so many new and fascinating things about CW.

I have a chromebook and no laptop, so I cannot enjoy the 3 D Colonial Williamsburg.

Please show us more of the 3 D Williamsburg as blog posts, so we can enjoy it, too.

I hope we’ll have a solution to this before too long, but in the meantime you can look at the 2D portions of Virtual Williamsburg if you select “Revolutionary City” or “Armoury” on the navigation.

This is a great project, especially since it’s one of the first and biggest misconceptions that visitors have when they start touring, no doubt — that what they see today is how Wmsbg. actually looked, at some point. Technology allows us to pull so many bits and pieces of research together, giving us a more accurate glimpse, at least.

I hope that there are dollars in the budget for some fake raw meat to hang in the market house . . . even if they won’t be authentically covered with flies 🙂

How about some fake flies? 😃

No to the question. I went back and got Virtual Williamsburg t partially work so I think I need to keep working on it. With all the Mac users today, I would hope there would be some tweaks to enable us to use this resource smoothly. Although - it could be operator error!

Any idea to actually use this on Chrome or Windows Edge Browser?

I’m sorry I can’t offer an immediate answer, but you can look at the 2D elements by selecting “Revolutionary City” or “Armoury” on the navigation. Hope that helps.

Virtual Williamsburg does not work with Mac’s Safari as far as I can figure out - any suggestions?

Deborah, I was able to get this to work just fine with Safari! Have you installed the plugin?