When did the American Revolution begin? With the Stamp Act protests in 1765? Shots fired on Lexington Green in 1775? The Declaration of Independence in 1776?

Wherever we decide to mark it, the milestones on the road to independence were interspersed with a thousand smaller steps, each one adding to the momentum that created, in the words of John Adams, a change in “the minds and hearts of the people.”

One such step occurred this week in 1774. From August 1-6, more than a hundred members of the recently dissolved House of Burgesses gathered at the Capitol to establish a plan to cooperate with the other colonies in resistance to what they considered their mistreatment.

It was the first, and probably least-known, of five Virginia Conventions that met over the two years preceding independence. This one would soon be overshadowed by the others. The second meeting, held in Richmond, produced Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death!” speech. The fifth produced a resolution for independence and the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Big stuff.

Still, the first convention was a significant moment in the history of Williamsburg—and the budding nation.

The seeds of the convention were sown in Lord Dunmore’s dissolution of the House of Burgesses in late May after they had the audacity to pass a resolution for a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer to express solidarity with Boston, whose port had just been closed until the troublesome New Englanders paid for all the tea they destroyed during their unlawful “party.”

The Burgesses were filled with righteous indignation. Retreating to the Raleigh Tavern’s Apollo Room after the dissolution, they issued a statement expressing their irritation with the governor and their belief that Virginia’s fate was tied to Boston’s: “An attack made on one of our sister colonies, to compel submission to arbitrary taxes, is an attack made on all British America, and threatens ruin to the rights of all.”

The statement also called for a “congress” with representatives from all the colonies to meet and “deliberate on those general measures which the united interests of America may from time to time require.”

Meanwhile, Peyton Randolph invited about 25 Burgesses to his home, where it was decided to invite their entire body to a meeting beginning Aug. 1.

During June and July counties across Virginia debated how to respond to the growing crisis. Many passed resolutions that were carried to Williamsburg for the August meeting. The boldness of the documents tended to reflect the sentiments of their representatives.

Richard Henry Lee wrote that there was “immense danger to America, when the dirty ministerial stomach is daily ejecting its foul contents upon us.”

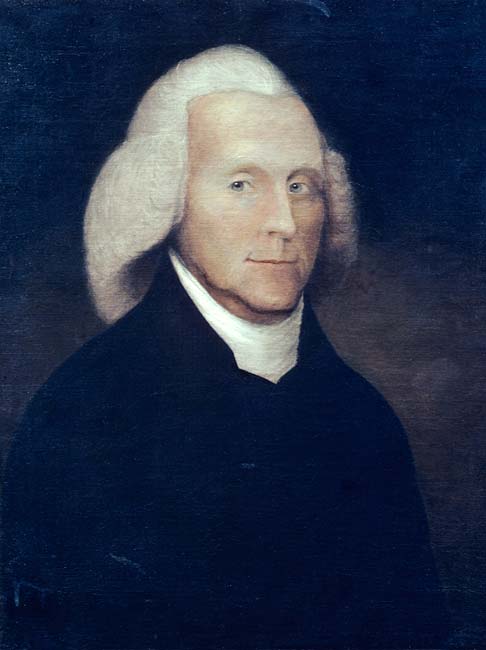

Edmund Pendleton

A statement from Caroline County, likely written by the moderate Edmund Pendleton, said, “Whoever shall go about to dissolve that union by attempting to deprive the Colonists of their just rights on the one hand, or to effect their independence on the other, ought ever to be considered a common enemy to the whole community.”

The Fairfax Resolves, drafted by George Mason, struck a more strident tone. Being subject to measures passed in Parliament, where the people of Virginia had no voice, was setting a course for “the most grievous and intolerable Species of Tyranny and Oppression, that ever was inflicted upon Mankind.”

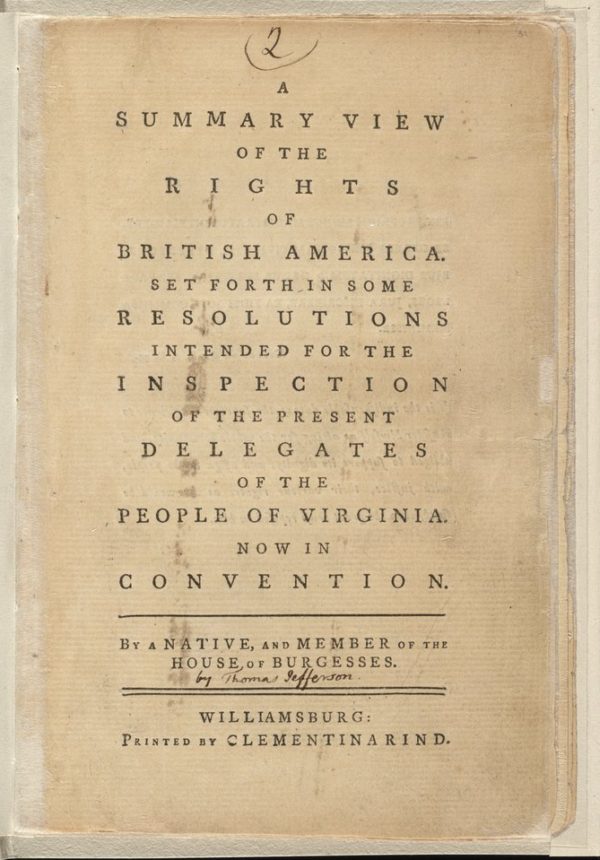

Thomas Jefferson weighed in with A Summary View of the Rights of British America, which he hoped would inform the discussion at the convention. But in late July he fell ill and never made it to Williamsburg. But he sent his long-time enslaved servant, Jupiter, to deliver copies to Peyton Randolph and Patrick Henry.

A Summary View was applauded by a gathering of about 25 delegates at Randolph’s house. And without the author’s knowledge, Clementina Rind, editor of the Virginia Gazette, printed copies for sale from the newspaper’s office in what is known today as the Ludwell-Paradise House.

When it came time to meet, Dunmore was still conveniently occupied fighting Indians on the colony’s western frontier. They met in the Capitol, with Peyton Randolph presiding.

Details of the proceedings are largely unknown. No written record is known to exist, and the newspapers—all three versions of the Virginia Gazette—waited patiently for an official report to emerge at meeting’s end. “It is not in our power,” wrote Clementina Rind, “to oblige the public with a particular relation of what has been done until next week, when we hope to publish all their proceedings, which we doubt not will be highly satisfactory to all the colonies.”

One second-hand (and otherwise unsubstantiated) report had George Washington rising to declare that he was willing to raise a thousand troops and lead them himself to relieve Boston.

In any event, the Convention included just over a hundred men out of 153 that would have been eligible. A pretty good turnout for an extralegal gathering.

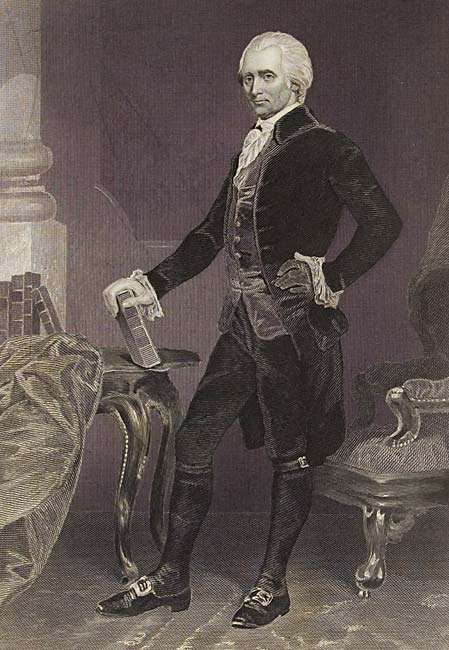

Richard Henry Lee

The Convention accomplished two objectives. First, on Aug. 5, they officially appointed seven men to represent the colony at the First Continental Congress, which would convene in Philadelphia the month following. They were: Peyton Randolph, who became president of the Continental Congress; George Washington; Patrick Henry; Richard Henry Lee; Richard Bland; Benjamin Harrison; and Edmund Pendleton.

In addition, on Aug. 6, the Convention unanimously adopted an association asking the people to voluntarily halt all direct and indirect trade with Great Britain. 108 delegates signed the document, including Thomas Jefferson, who may have appointed a proxy to sign for him during his illness.

The document opened with a declaration of loyalty to the king, targeting Parliament for “ill advised regulations” and “several unconstitutional acts.”

The main measures included a pledge to halt the importation of all British goods, and slaves, after Nov. 1, 1774; a halt to exporting the next season’s crops beginning Aug. 10, 1775; and a threat to punish any merchants who failed to abide by the association agreement.

The new symbol of tyranny-tea-was singled out for special treatment. Since tea was “the detestable instrument which laid the foundation for the present sufferings,” it should not even be consumed at home, much less purchased. In addition, a full boycott of the British East India Company, whose tea had been dumped in the harbor, would be necessary if Boston was forced to pay for it.

The eleventh of twelve points was addressed in a public meeting called by Peyton Randolph the following week at the Courthouse, where the Association was discussed and a generous allotment of “cash and provisions” were collected for the people of Boston.

John Adams read of the events in Williamsburg in a Virginia Gazette he came across in a New York coffee house. “The spirit of the people is prodigious,” he wrote in his diary. Their resolutions are really grand.”

In October 1774, the First Continental Congress passed a set of Declarations and Resolves that echoed the effort of the Virginians. The Continental Association was born, and the cause of Boston had clearly become the cause of all the colonies.

Thanks, Bill, for explaining this oft-overlooked milestone on the road to revolution. Good stuff. I’ve shared it on my public radio show’s Facebook page: http://www.facebook.com/Your.Weekly.Constitutional.