75 years ago today, Chowning’s Tavern opened for business. Like the original, the reconstructed tavern catered to a “less-august clientele” than the 18th-century Raleigh or King’s Arms Taverns. That made it really strange when the very first customers happened to be movie stars.

Joan Fontaine and Brian Aherne were touring the eastern seaboard by private plane when they landed in Williamsburg for four nights. Aherne made more than 30 movies and had some renown, but the 23-year old Fontaine, who had recently finished filming the Hitchcock thriller Suspicion (for which she took home the Oscar for Best Actress) soon eclipsed him. Sadly, we don’t appear to have photographic evidence, but the Hollywood couple reportedly had dinner at Chowning’s each night they were in town.

Chowning’s rose where the old Colonial Hotel had stood since 1895. After the Colonial was torn down, archaeologists scoured the site for evidence of 18th-century uses.

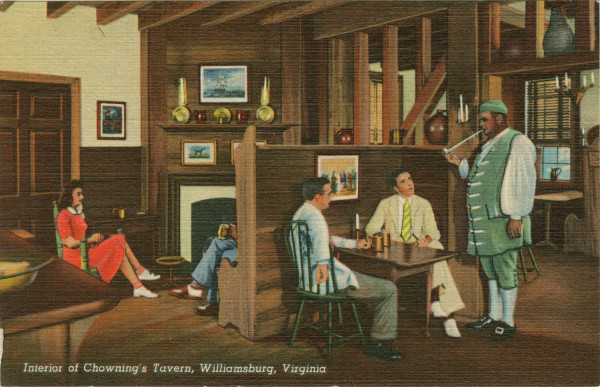

The reconstructed tavern was built on the original foundations of two buildings that were joined together. The design reflected the fact that the two sides had different histories. From 1745 to 1765 the occupants included a tailor, blacksmith, butcher, merchant, wheelwright, and “spinster.” The west building, favored by merchants, was slightly fancier. The east building, where the blacksmith was among those plying their trades, had a rougher look, with booths and darker wood.

Inside, the space was decorated with antiques and reproductions based on 18th-century tavern inventories. Among the authentic items were leather furnishings, pewter, glass, and crockery. The portcullis bar mimicked the fortress-like one in the Raleigh.

Backgammon and checkerboards were painted on two tables. 18th-century prints (“representing both the sublime and the ridiculous”) adorned the walls. At the time it was noted that period prints were easier to acquire because of the war raging in Europe. Of course, in just a few short months, the United States would be fully engaged World War II as well.

Servicemen, who were welcomed in droves to Colonial Williamsburg during the war, were many of the tavern’s early customers.

Courtesy Curt Teich & Co., Chicago, Ill.

John Green, the general manager of hotels and restaurants for Colonial Williamsburg, may very well have been spinning a yarn, but he claimed his research of old prints suggested tavernkeepers were typically “gargantuan individuals.” Failing to find a suitable giant in town, he claimed that he dispatched an assistant to the far reaches of the state to find a likely candidate for the role. Thus was Mr. Julien Dickens, six-foot-two and 290 pounds, brought into the fold, from his home in Capron near the North Carolina border.

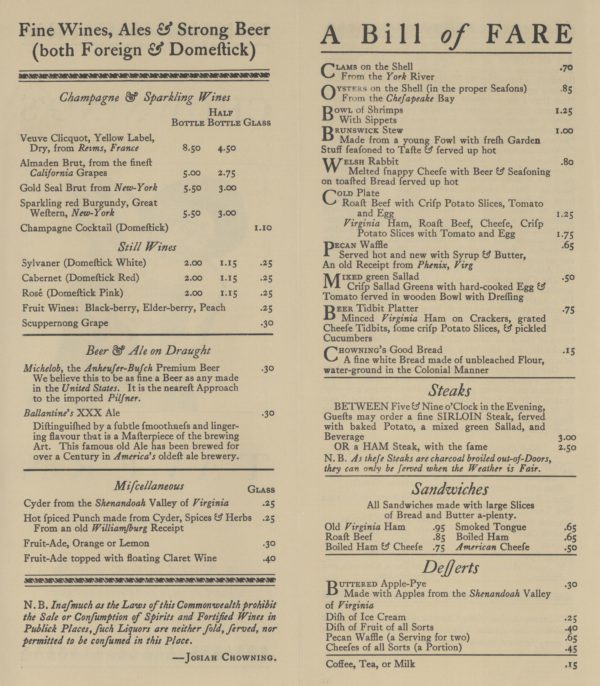

A Chowning’s Tavern menu from 1955

The menu offered food to go with a drink: buckwheat cakes and country sausage, Smithfield ham, and steamed clams. A sandwich would set you back anywhere from 20 to 35 cents. (Prices were a little bit higher by the time the menu above from 1955 was in use.) So we’re talking upscale. In addition to draft and bottled beer served in 19-ounce pewter tankards, guests could enjoy orangeade, lemonade, and ginger beer until the 11 p.m. closing time, midnight on Saturday.

The tavern also provided long clay “churchwarden” pipes for customers to smoke at no charge. The tobacco was even provided.

Every effort was made to disguise modern systems. A cooling system, for example, was rigged from the basement to chill the beer on tap, delivering it to customers via three old kegs. Shortly after opening, Green commented, “At least ten people a day ask the bartender how beer can get so cold in a wooden keg.” The illusion was confirmed.

OK, cold beer is important, you say, and we would all like to have a good 20-cent sandwich, but who, you ask, was Josiah Chowning?

And I’m here to report we don’t know a whole lot about him. Here’s what we do know, fragmentary evidence that Colonial Williamsburg historians have pieced together over decades.

By 1752, Chowning owned an estate a few miles from town at Powhatan Plantation in James City County. We know this because he placed an ad in the Virginia Gazette looking for a stray horse. The farm had a barn, various outbuildings, and an orchard with apples and peaches. At his death, it spanned 235 acres.

His wife was Mildred; we can’t say whether or not they had children. They likely owned more than a handful of slaves. We know one, Nero, by name.

Early in 1765 Chowning paid seven shillings to advertise the tavern in the Gazette. In 1766, the newspaper advertised the establishment as a place “where all who please to favour me with their custom may depend upon the best of entertainment for themselves, servants, and horses, and good pasturage.”

It operated for less than three years. In April 1768, William Elliott was running the tavern. But within months it was a wigmaker, Walter Lenox, who operated his business and rented out rooms there.

Mr. Chowning died by April 1772, age unknown, survived by Mildred.

So what about the never-ending controversy: How do you pronounce “Chowning”?

It’s puzzled us for years because there is no definitive evidence. A memo from 1949 laid out every possible option. Chowning was often spelled Chewning, so was it the same name? And what kind of “ew” or “ow” was it? Did you say it like cow, show, few, sew? The memo seemed to come down on the side of “show,” which would give it a long-o sound.

Chow, as in hoe. Yikes.

In 1981, the question was revisited. Although we didn’t know how the name was pronounced in the 18th century, it was pronounced CHEW-ning generally today, at least in Virginia. And since spelling was not standardized in colonial days, it was reasoned, it was perfectly possible that the variant spellings reflected the difference between original, actual, spellings, and a phonetic spelling.

So the decision was made to go with “chew.” That, of course, settles nothing. (Ask anyone seeing “Botetourt” for the first time.)

The garden in back of Chowning’s, which is pleasantly situated for a drink or a meal in sight of the Courthouse, was part of the original plan, although it wasn’t present at the opening. The foundation’s internal newsletter, The Restoration News, reported the proposal for “arbors and booths of greenery” for the back, noting that such spaces were regulated because they could become something of a public nuisance.

“Modern arbor-haunters,” they advised, “will please confine themselves to silent song and genteel jests.” Today, Chowning’s has returned to its roots as an 18th-century alehouse, but not even the staff observes such restraint. We offer no such restrictions, and heartily encourage all to join us for laughs as hearty as the meals, and singing as strong as the adult beverages!

I remember the “official” change in pronunciation from “Chownings” (like dog chow) to “Chewnings” decades ago. But now I’ve noticed in your videos that interpreters and others seem to have gone back to “Chownings.” Is this per another official pronouncement (pun intended.)?

I’m not sure how universal it is, but there has been a recent move toward “chow” that I believe is meant to put guests at ease.

I know there were never any musicians dressed in 19th and 20th century costumes playing Irish pub music outside of Chowning’s in the 18th century.

Among the early servers at the taverns were William and Mary undergraduate male students.. The students were given preference for the cherished waiter jobs and I believe they formed an alumni group at W&M know as the “Order of the White Jackets”. Shortly after I graduated I had the honor to meet one of them, a doctor from New Jersey. In addition to tips they probably learned a lot about humility.

Ed McManus

The original advertisement read, “In 1766, the newspaper advertised the establishment as a place “where all who please to favour me with their custom may depend upon the best of entertainment for themselves, servants, and horses,..”

I would love to know how the horses were entertained. ROFL (or the colonial version of “ROFL.”)

And remember, a good Tidewater Virginian pronounces where (s)he is from as “Tied wodah Virginiar”. 😉