I put the 3-D glasses on as instructed and gaze into the screen as the image comes to life. A room, rotating slowly. There is the clank of metal as a door unlatches. Voices at the bottom of the stairs, then footsteps.

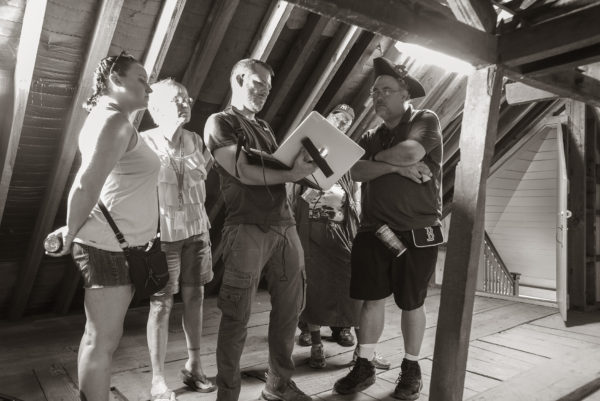

Brian Emery, Associate Professor of Photography at the Fashion Institute of Technology, might seem like an unlikely candidate to be conducting a study of the attic at the Robert Carter house. I tell him as much, and he agrees.

Brian has been a visiting research fellow at Colonial Williamsburg for about six weeks, and his work is a somewhat unorthodox blend of art, photography, and the intertwined histories of the Carters and the foundation that preserves the family house.

We’ve been going back and forth for a while, with me trying to coax for a deeper explanation of what drove an art professor who disavowed any previous interest in Colonial history to spend much of his summer in a sweltering third-floor room taking pictures. (Admittedly, they’re pretty cool pictures.)

Brian can tell I’m not getting it, and that’s why he hands me the 3-D glasses so I can take a look at the multimedia video he’s working on. It’s essentially the rough draft of his research, and if all goes well, it will help Colonial Williamsburg take another step into the future of a more immersive virtual experience for our guests.

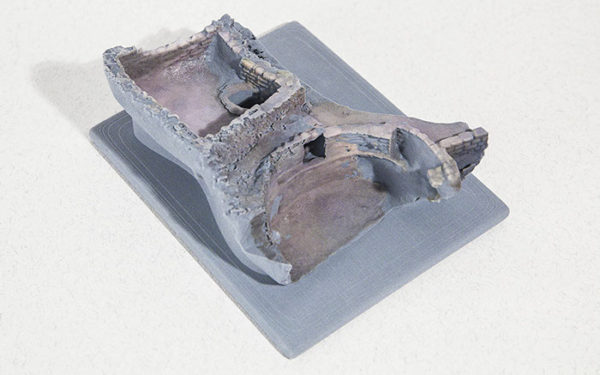

The video, if that’s the right word for it, is entirely set in the Carter attic, where our architectural historians are currently trying to solve a mystery. They’re examining clues—a fragment of plaster wall (above), framing for a door that must have locked from the inside—with the hope that the house will give up the secret of what purpose the space served. That includes the distinct possibility that enslaved members of the household lived there in the mid-1700s, but at this point we don’t know whether the evidence will be definitive one way or the other.

On the computer screen, the 3-D image of the attic spins, the barest of structures, just wooden posts, dark corners, and a slanting roofline. It does offer quite a clear perspective of the original M-shaped roof that was replaced in 1758. As the image rotates, an assortment of people—or at least their avatars—assume different positions in the space.

The accompanying soundtrack consists of spliced recordings of our architectural historians explaining the attic’s history and others just exploring the space. This includes costumed interpreters playing the roles of people who might have been there 250 years ago, people like Robert Carter III, who owned the house for a period, and others portraying enslaved Virginians.

So how—and why—is Brian doing this project?

It started last year when he planned a trip to the Southwest with the express purpose of experimenting with three-dimensional photography. Convinced that advances in technology were in the process of reshaping the very way we perceived space, he wanted to see how he might use the new science to create a different kind of art.

On this busman’s holiday he made scans of thousand-year old pueblos and kivas (ceremonial spaces). Armed only with an off-the-shelf 3-D webcam/motion tracker which attached directly to his laptop, Brian wanted to find out whether looking in a new way could unlock the potential of seeing in a new way.

When he returned, he printed out models of the ancient spaces with a 3-D printer.

Months later, he learned about Colonial Williamsburg’s fellowship offering for someone working with 3-D photography. He proposed creating 3-D prints like the ones from last year’s trip. The absence of a background in academic history proved to be no obstacle, and here he is.

Brian arrived with little in the way of preconceptions. This would actually be his very first time setting foot in Williamsburg.

Aside from the daunting scale of the place, he was most surprised—pleasantly!—to discover just how much of the foundation’s is a research institution. The work to understand, unearth, and interpret Virginia’s past is ongoing, and every year yields new discoveries and deeper understandings.

Early conversations convinced him to join the team intensively studying the Robert Carter House. “I like spaces that are a little ambiguous,” he says.

The methods Brian is playing with carry profound implications for how we might “see” the past. Interestingly, Brian has no illusions of accessing the past on its own terms. He is consciously embracing the present-ness of his project. He is not looking for a moment in time. His multimedia video underscores the point, since it is more of a meditation on a space with a long history and the many people who walked its floors, including the present crew of researchers.

The sparseness of the top floor has proven to be a little bit of a drawback. Beyond the posts, beams, and roof supports, there isn’t much to the space. It “lacked mass.”

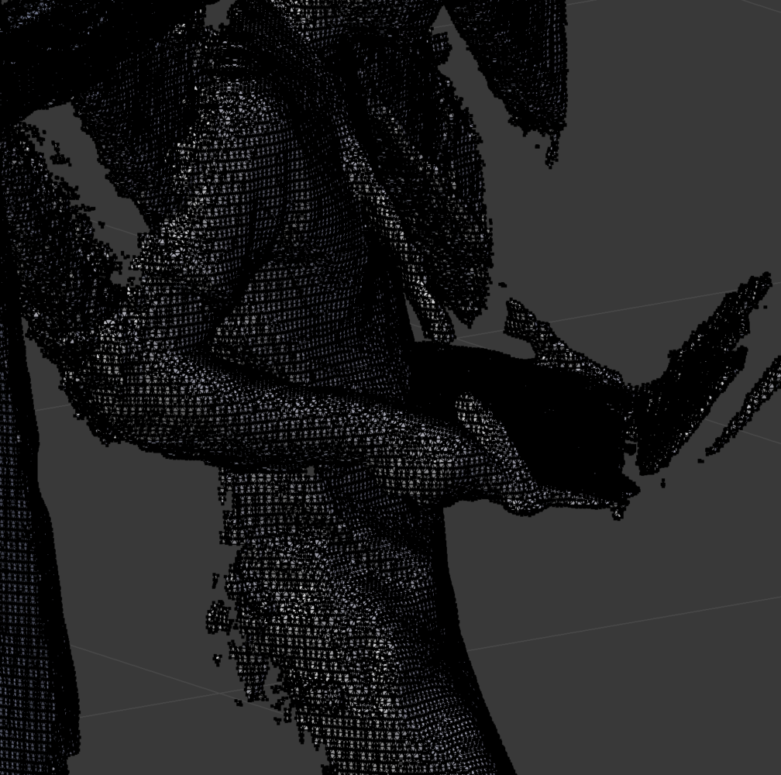

Nonetheless, he has spent as many days as possible making the 3-D scans of the attic. The scanner features a camera similar to what you’d find on your smartphone, which can capture about 30 frames per second.

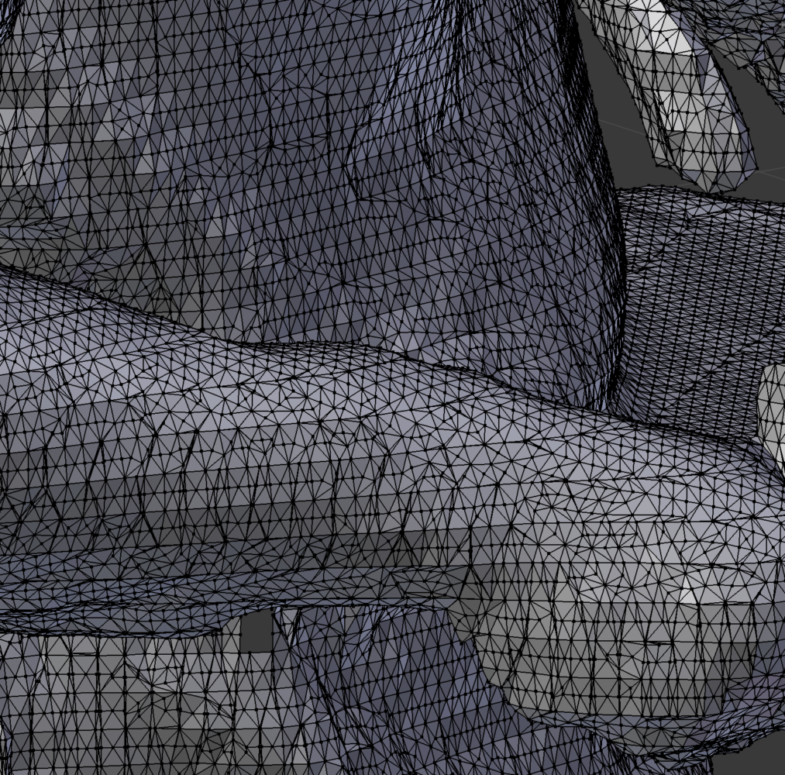

That’s supplemented with an infrared light emitter, which emits beams that are captured by an infrared camera. The software puts all the data together to produce a high-density depth map. It has amazing quality, producing full-color scans with two million vertices.

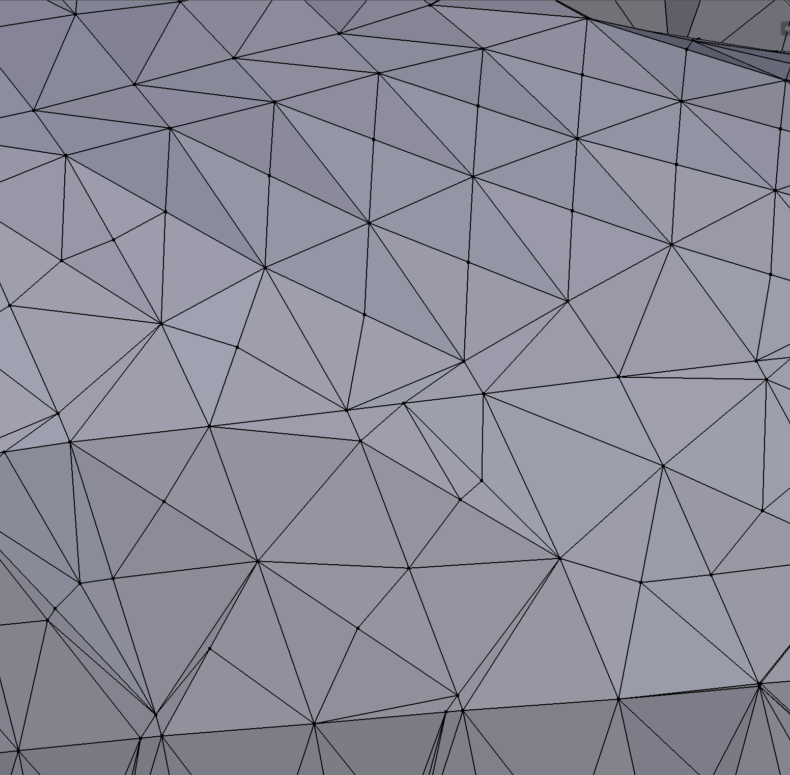

In other words, a lot of detail. You can see just how much in the images above. The left image shows the “picture,” the middle in more detail. The image on the right shows the geometric base of the mesh-like surface. Just a bunch of triangles.

Each scan captured a part of the room from a particular angle. Many had to be redone when he found flaws, such as an unilluminated corner, in the first attempts. It took 150-200 of the images, painstakingly pieced together, just to make the model of the architecture. Part of the reason is that Brian is pushing the technology, which was intended for use in video game systems, to its limits.

My wife and I were fortunate to get a bit longer than usual tour of the Carter House in one of “The Building Detective” programs. Brian was in the attic that day doing some of his work and we talked to him a bit there. Then we saw him at lunch time behind the palace during one of the programs featuring African-American life in the 18th century. It was about the reaction to a group of slaves to the news they were about to be auctioned off, and probably separated.

Before the program began we had a more extended conversation with Brian. I was fascinated by the techniques involved. I think there is very strong possibilities in this. It can take the advantages of photography in restoration to an exponentially greater level.

Brian and Colonial Williamsburg are benefitting one another, and ultimately benefiting future visitors and others who will have access to the out put of these studies.

A very interesting and provocative project-good work!