“They don’t make ‘em like they used to” is how the saying goes. In the case of some 19th-century German-made toys, that might be a good thing.

This October, our Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum will open a new exhibit called “German Toys in America”, featuring a whimsical variety of 19th-century German-made toys including soldiers, farm animals, dolls, and even squeak toys. As part of her research in preparation for the exhibit, Jan Gilliam, Colonial Williamsburg’s Associate Curator of Toys, asked if I might analyze some of the toys to determine whether these playthings held any dangerous secrets behind their cheerful appearances. She was particularly interested in identifying any toxic paint pigments. Hazardous materials in paints are a concern today, but Jan’s research found that as far back as the mid-19th century, parents were warned that certain paint colors in their children’s toys could be poisonous, and to take care.

Vermilion pigment. Forbes Collection. Photo Credit: Keith Lawrence, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Emerald green pigment. Forbes Collection. Photo credit: Keith Lawrence, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Some of these toxic pigments include lead white (2PbCO3 · Pb(OH)2), which was the most widely-used white pigment in paint since early times. In fact, lead white was used in the United States until as recently as 1974! Red lead, or “minium” (Pb3O4), is a bright orange-red pigment that also contains lead. Two green pigments, Emerald Green (Cu(C2H3O2)2 · 3Cu(AsO2)2), and Scheele’s Green (Cu(AsO2)2), both contain arsenic. Vermilion (HgS) is a bright red pigment that contains mercury. Definitely not “kid-friendly” by today’s standards!

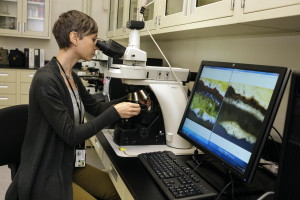

To identify these and other pigments in the painted toys, I decided to carry out the analysis with our handheld XRF (X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometer). This instrument uses a beam of low-power X-rays to determine the elemental composition of an object, particularly on its surface. Knowing the elements present helps me determine which pigments might also be present in the target paints. This type of analysis is non-destructive, meaning it does not require a sample and does not damage or change the object. Since the toys were all so very small, this technique was the most appropriate to use.

The XRF is connected to a laptop with software that allows me to interpret the data immediately. The analysis itself is a relatively rapid process, each run being about 30 seconds long. I was able to complete all of the analyses in one morning. Getting the results to the curator as soon as possible gives them more time to prepare for the exhibit.

This little cow (1960.1200.10,1) looked very startled during the procedure but he had nothing to fear.

The results suggest his red-brown body paint contains mostly iron and calcium, probably an iron-oxide red with a chalk additive. The white stripes along his back contain mostly zinc and barium, most likely a zinc white mixed with barium sulfate pigment. These paint pigments are relatively safe.

This soldier (1962.1200.15), however, contained some dangerous materials.

While the green paint on the base did not contain arsenic, the red stripe on his uniform contained both lead and mercury, probably a mixture of minium and vermilion pigments. The yellow paint contained lead and chromium, most likely from a pigment called chrome yellow (PbCrO4). His white trousers, however, contained mostly calcium and were therefore a safe, chalk-based white.

This soldier (1971-854,1) is one of a set of five. He also contained some hazardous pigments including lead and mercury.

I analyzed five different areas on the soldier (1971-854,1) and overlaid them in the software for comparison. Lead was detected in four areas: the white trousers, the blue jacket, the red stripes, and the green base. The only area that did not contain lead was the painted metal rifle, which contained titanium. This suggests the presence of titanium white (TiO2), a white pigment that dates to the early 20th century. Therefore, this rifle is most likely a later addition or repair.

The XRF needs to be constantly re-positioned to make the closest contact with the surface being analyzed. This tripod helps me maneuver the instrument more accurately than if I held it by hand. Due to the rounded surface of the top of this figure’s hat, it took some finessing to get the best position.

This figure of Noah (1971-810,5), was finally all set for analysis and he looked like he was about to get beamed up to outer space!

While Noah’s black hat contained no hazardous materials, he might want to re-think his scarlet garment. It contained high amounts of mercury, lead, and sulfur; probably from the presence of vermilion and red or white lead pigment.

Roughly half of the toys I analyzed contained pigments we would consider hazardous by today’s standards. I never found any arsenic-based pigments, but by far the most commonly used pigment was white lead. Many of these same pigments are found throughout our collection, in paintings and decorative objects. The danger here is, of course, that children of the 19th century were not so different from children of today. These toys would have been excessively handled and probably chewed, which would have led to ingestion of any toxic materials. Luckily, children’s toy manufacturers today have much more rigorous safety standards!

I loved having these whimsical toys in my laboratory for the day. In fact, this was one of my favorite projects ever. It still amazes me how much can be learned from historic materials using non-destructive techniques like XRF. Each object has a story to tell and analysis is just one way to shed light on our past and learn how those before us lived, worked, and played.

Please visit the exhibit this October to learn so much more about 19th-century German Toys in America!

GUEST BLOGGER: KIRSTEN MOFFITT

Kirsten received her M.S. from the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, where she specialized in the conservation and analysis of painted surfaces. As Colonial Williamsburg’s Materials Analyst and Associate Conservator, Kirsten analyzes all types of collection materials including metals, ceramics, textiles, furniture and house paints in the Foundation’s newly established Materials Analysis Laboratory. She loves that her job is a combination of art history, chemistry, and forensics. Kirsten truly loves watching paint dry, and her analytical work was a big contribution to Benjamin Moore’s Williamsburg Collection line.

Kirsten received her M.S. from the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation, where she specialized in the conservation and analysis of painted surfaces. As Colonial Williamsburg’s Materials Analyst and Associate Conservator, Kirsten analyzes all types of collection materials including metals, ceramics, textiles, furniture and house paints in the Foundation’s newly established Materials Analysis Laboratory. She loves that her job is a combination of art history, chemistry, and forensics. Kirsten truly loves watching paint dry, and her analytical work was a big contribution to Benjamin Moore’s Williamsburg Collection line.

Kirsten loves reading, traveling, and walking her black lab, Ebbie, around the Historic Area.

I would be interested in an offshoot study about children’s, mystery illnesses, deaths, and handicaps that may have actually related to their toys.

Interesting article. Childhood in UK was very different in the past. Children that could have toys bought for them or made for them, did not play with toys every day like mid 20th Century children did. You read of children getting their toys out of the toy cubboard/box only on Sunday, after church/ Sunday School and only if they had been particularly good. Then the toys were played with carefully and then packed away again for another week. Germany provided most of the wooden, porcelain (dolls) and tin & clockwork toys until the First World War (1914-18 in UK). Then it became politically incorrect to buy toys of the then ‘enemy’ so many British toy companies set up making the toys that could not be imported, or by the 1930’s escaping Jewish families from Germany, set up in UK under different none-German sounding names.

Probably the poorer children were less at risk than the children of wealthier parents, who could afford these toys. The poorer parents probably gave their children more home-made items, which might’ve had less paint (paint being just another expense).

That is a really good point.

Very interesting. We use xrf in the lab I work in, but it is for elemental analyses of catalysts. Not nearly as interesting as this application.

It is something to ponder how paints and make-up and medicines, and other materials often had hazardous components. It would add value to the exhibit if what you discovered can be included in the displays of the toys in some way.

In the very early 1970’s I worked on a large boat on the Chesapeake Bay while in my late teens. I was often called upon to chip rust on the inside of the hull of void spaces and paint everything with “Red Lead”. There would only be a small hatch to get in and out and no ventilation or masks. I can only imagine my exposure levels.

Again, a good article. Getting information on what exactly things are made of increases our ability to get to still deeper storys of our past.