In the shade under a canvas tarp stands a barrel and a considerable pile of manure—what’s not to love? I’m in the backyard of the Powell House checking out our newest old experiment, an 18th-century egg incubator.

The project came together in just a few months, prompted by a basic question: What else can we learn about how poultry was raised 200-odd years ago?

After perusing various histories and practical guides, Layne Anderson, one of our wonderful Livestock Husbanders, was intrigued by The Art of Hatching and Bringing up Domestick Fowls by the French scientist René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur. Its first English edition was published in London in 1750.

Réaumur was looking for “a method of hatching chickens without the help of hens,” that is, artificially incubating eggs to maximize the production of chickens that could be raised for food. The system he outlined theoretically made it possible to incubate hundreds of eggs at a time. Such experiments were not only characteristic of scientific inquiry during the Enlightenment, they addressed issues of feeding growing urban populations more efficiently.

Now, Colonial Williamsburg is putting Réaumur’s method to the test.

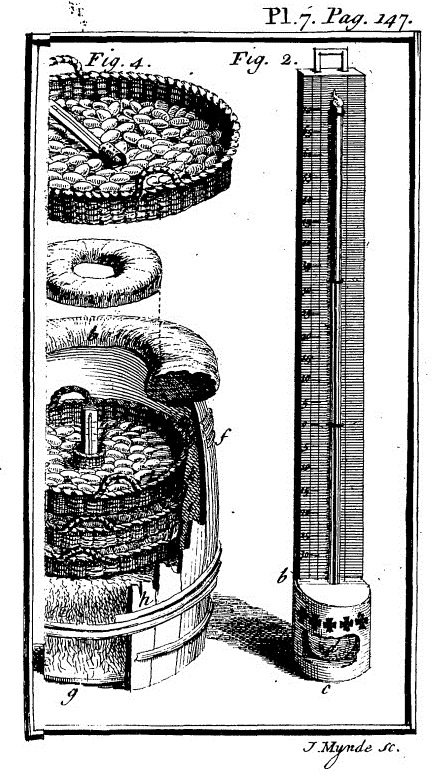

The magic happens in a “hatching barrel,” a used bourbon barrel with about a 36-gallon capacity that was salvaged by Journeyman Cooper Jon Hallman. Réaumur advocated the use of such “wooden casks” because they would be cheap and easily available to most people.

An average hen will lay one egg every day or so. After she decides she has enough (which is about as much deciding as a hen does), she will start to sit on her clutch (the group of eggs she laid). Only then does the 21-day incubation period begin.

We’ll be starting with about a dozen freshly-laid eggs from our hens. After piling an insulating layer of straw at the bottom of the barrel, the eggs will be placed in one of the custom-made baskets made to hang on the inside.

The two baskets were woven by our Basketmakers based on examples in The Art of Hatching. They usually work with split white oak, but branched out into willow for this project because that’s what is shown in Réaumur’s illustration. The larger basket is about 14 inches in diameter with four handles, and the smaller one is about 13 inches with two handles.

Journeyman Basketmaker Kristy Engel explained that several weeks were spent figuring out their approach to the task: experimenting with soaking time for the willow (to make it more pliable), figuring out the right-size material, and learning unfamiliar weaving techniques. But they were up to the challenge, as you can see in the slideshow below, which shows some of the process.

- 1. The largest-sized willow was bent into hoops to form the bases for the two baskets.

- 2. The hoop was bound together with a thinner willow skein.

- 3. This is a type of weaving called “fitching” to create the open work in the base.

- 4. The two completed bases.

- 5. The side stakes have been put in place.

- 6. Weaving up the sides.

- 7. The larger finished basket contains a mini-basket to hold the thermometer.

Réaumur’s whole scheme was an attempt to adapt known methods of artificial incubation to England’s social and geographic circumstances. He was particularly enthralled with a method used in Egypt, where large ovens, known as “mamals,” were used to hatch thousands of chicks at a time. Every autumn people from the small village of Berme, located “within twenty leagues of Cairo,” would scatter across Egypt to tend local incubating ovens. Details of their technique were said to be a closely guarded secret that was passed down through the generations.

But the secret, Réaumur believed, was not in the construction of the ovens, which were, after all, in plain sight. Rather, it was the mystery of how to maintain the temperature well enough to “fool” the eggs into hatching—and not just end up as a very large order of fried eggs.

That’s where the manure comes in.

“Dung,” wrote Réaumur, “to which we compare all the things we look upon as most abject and most despicable, deserves to be ranked among the greatest presents nature can possibly make us.” Ah, Mssr. Réaumur—man of science, hopeless romantic.

But it does come in handy for keeping eggs warm, and we just so happen to have a ready supply around here. Initially Layne planned to use manure picked up from the street, but it decomposed too fast, so the supply is coming primarily from the stables and the ox pasture.

Our Historic Gardeners use manure to heat their hot beds during the winter, so Layne tapped Journeyman Jen Mrva for expertise on maintaining a proper dung pile. Jen explained the need to use fresh dung, how to gauge the right moisture level, and the importance of turning the pile frequently to even out the heat.

The manure will be about a foot-and-a-half deep in a two-foot radius all the way around the barrel. A hen’s natural body temperature runs about 104 degrees, so we’re aiming to keep the eggs at a steady 101. The temperature must be closely monitored. The lid on the barrel can be used to regulate the heat.

Apprentice Tinsmith Joel Anderson took on the task of making the thermometer as pictured in Réaumur’s treatise, which was a project in its own right. After Coach & Livestock purchased basic glass thermometers, Joel worked with Journeyman Cabinet Maker Brian Pavlak to shape, cut, and mark a piece of scrap maple for the frame. Joel said the hardest part was trying to figure out how to mark it properly with numerals.

“I ended up stamping the wood with printer’s type and then blackened the indentations with charcoal dust,” said Joel. “Then I varnished the wood with copal from the Wheelwright’s paint resources, and installed the parts.” Staples and tacks from the Blacksmith Shop were used to fasten the tin shield, punched with a Maltese cross pattern, to the wood frame.

There are also plans to use a “fat thermometer” soon. Seriously old-school method. Just mix two parts butter with one part tallow, put it in a jar, then watch how runny it gets. Over time you learn the viscosity of the mixture at particular temperatures. Layne says they’ll want it to be slightly runnier than it would be if you put it under your armpit. Okaaay.

High and low temperatures aren’t the only risk to the hatchability of the eggs. We’re taking Réaumur’s advice to “hinder the noxious vapour” from the manure with “thick coarse brown paper pasted all over the inside of the cask.” Left unchecked, the emissions from the manure would suffocate the soon-to-be-chicks, who need their oxygen. The lining also helps to regulate the humidity; too much could cause the eggs to rot.

The eggs will be turned and shifted around by hand four or five times a day to keep their progress even. (The hen normally rotates eggs around while they are incubating—and here I thought she was just sitting there for three weeks.) If you don’t turn them, the membranes that form around the developing embryo can get stuck, and the chicks won’t be able to hatch out. Each egg will be marked with an “x” on one side and an “o” on the other to keep track of the turning.

A brooding hen will be taking up residence in the small stable next to the incubator, and a dummy version of the incubator (with wooden eggs) nearby, providing additional educational opportunities for guests.

The Powell House will be open daily through Sept. 1 from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Interpreters from Coach & Livestock will be on site to check on the progress of the incubator daily, however, there is no set schedule. But the Powell House staff will be able to guide you during regular hours.

Will we soon hear peeping behind the Powell House? It’s too early to know if the experiment will be successful, and perhaps it bears repeating that you shouldn’t count your chickens before they’re hatched.

Cindy says

Sooo, Bill Sullivan, did you follow up to see if the eggs hatched? We’re waiting to find out! Wondered if they had any way of incubating before the days of electricity.

Glad you asked! We posted an update just a few days ago: http://makinghistorynow.com/2016/09/lesson-learned-dont-count-your-chickens-before-theyve-hatched/

This is an exciting experiment. I read Réaumur’s book back in 2008 and was quite curious about all his ideas. I did try one of his ideas.

Réaumur claimed that the best way to preserve eggs is with a spirit of wine varnish (aka shellac.) He states that eggs treated this way will remain so fresh that two years later, after removing the varnish with alcohol, the eggs could still be hatched into healthy chicks.

I carefully shellac’d 18 eggs and set them away at normal room temperatures. After 1 year we placed 6 in an incubator after removing all the varnish with alcohol. No chicks hatched out. Six of the remaining eggs were candled and then opened to see what the egg itself looked like. Although they were not rotten, the yolk was decomposed inside and some of teh shells had some black staining in spots. The other six were kept until the second year when they looked pretty much the same inside as they had the first year. A total fail.

I will be anxiously awaiting the results of your experiment with the hatching barrel!

* the eggs used were clean Dominique eggs fresh from my chicken house.

Absolutely fascinating article! Can’t wait to see the results!

We have raised chickens on our little farm for three decades. Lots of free ranging and natural hatching happens.

Our experience is that somehow one hen goes broody and most if not all the others start laying in one nest, even though they had not been doing so previously. So a good number of eggs are accumulated in one nest over just a couple or three days. We have one hen that is particularly good at the task of turning and taking care of things, and patient with the chicks once they hatch. Quite protective. For instance she had them out the other evening and one of our cats was insanely curious and getting closer and closer. At a certain point Buckbeak (the mother hen), took off after her and chased her off.

We have never hatched with an incubator, and it will be interesting to read how this experiment works out.

I believe that chickens breeds of earlier times did not lay eggs as relentlessly as the modern breeds do. I can’t imagine it is natural or necessary for a hen to lay a couple hundred eggs in one year.

When one walks into an air-conditioned grocery store (music always playing in the background) today to buy a clean carton of eggs and a chicken, and then compares the ease of this with what you’ve described (not to mention the smell), or even onto a farm where hens roam free-range, and compares such with this - wow. We aren’t half the folks our ancestors were.

And in the height of a Tidewater VA summer too! Good luck!