“We’re looking for ghost marks,” explains architectural historian Carl Lounsbury. Spots, discolorations, bumps, ridges, holes, puckers, and other scars—we’re on the lookout for a whole host of imperfections. Not to cover them up, but to record them. As participants in the new Building Detectives program, we have a unique opportunity to observe and actually contribute to a new study of one of Williamsburg’s most historic homes.

It’s the Robert Carter House, a stone’s throw from the Governor’s Palace on the west side of Palace Green. For well over a decade it’s been used for office space and intermittent programming. Now, with the help of guests (that’s us), it may be taking the first steps toward renewed prominence.

Our primary tool is a flashlight. It’s amazing what details are revealed with a beam of light and some close attention to detail. Divided into small groups, we make our way through several rooms on different floors, examining how the house was constructed and modified, and what that means for our understanding of the lifestyle of its famous residents.

But there’s real work to be done. Over the course of the summer, participants in the program will be able to help with the task of recording every single piece of evidence the house contains, what our architectural historians call the systematic documentation of the physical fabric.

The “fabric” includes every element of the structure: beams, railings, walls, even the paint. It includes what is in plain sight as well as what lies underneath. The purpose is to understand how the house was put together as well as how it changed over time. Secrets will be revealed.

So you might get the opportunity to measure different spaces, mark holes in the floor with small color-coded stickers, or put the flashlight to good use in the search for elusive pieces of evidence. They love to put the kids to work in particular. (The program is recommended for ages 8 and up.)

The home is named for a man generally considered its most prominent resident in the critical years of the late 1700s, Robert Carter III. Carter is best known for making one of the largest manumissions of slaves in that period, at a moment after the Revolution when moral opposition to slavery was cresting and it really did seem possible the institution was in irretrievable decline. In 1791 Carter began freeing his human property. Within his lifetime 452 people gained their freedom.

So the structure was already notable, but recent discoveries have made the case for its significance even more compelling. First, dendrochronology revealed that the house, known from documentary evidence to have been built no later than the 1740s, was actually much older.

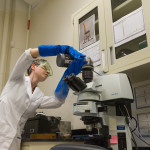

In dendrochronology, small samples are taken from wood—in this case, from several places in the framing, such as the one above. The ring pattern in the wood is compared against previous building and tree samples. Trees grow more in wet years than in dry ones, for example, and over time this creates an identifiable growth pattern, making it possible to determine the exact year, in many cases, when the timber for a structure was harvested.

In this case, it turned out that the trees that were used to frame the Carter House were cut down in the winter of 1726-27. That meant that it was built by Robert III’s grandfather, Robert “King” Carter, one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the history of Virginia.

At that time Carter was president of the Governor’s Council and the de facto governor of Virginia while the office was vacant. He wouldn’t have made the impolitic move of occupying the Governor’s Palace, so he did the next best thing: he built it as a residence practically next to it.

This means that this is the only building that Carter actually lived in that survives to this day.

The home had other illustrious residents. Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie lived there for a time when the Governor’s Palace was undergoing renovations in the 1750s. Robert Carter Nicholas, Virginia’s treasurer and a member of the House of Burgesses, purchased it in 1753. He sold it to his cousin Robert Carter III in 1761, and it remained in his hands until 1801. Colonial Williamsburg purchased it to be part of the restoration in 1928.

A second discovery is still shrouded in mystery. The attic, where appears to have been framed as a room, probably at the same time as the roofline was altered in 1758. The original M-shaped roof, a fascinating architectural artifact in its own right, is still plainly visible under the raised roof. The space may very well have been occupied by an enslaved resident in the Nicholas household. Right now it’s only a hypothesis, but the hope is that further study will yield additional evidence and more definitive answers.

This illustrates the fact that like our archaeologists and our academic historians, our team of architectural historians is actively unearthing new information about the history of Williamsburg. They are not merely caretakers, but researchers whose work continues to advance our understanding of the physical space of Williamsburg, sometimes one row of nail holes at a time.

Building Detectives runs at 9:30 a.m. and 10:45 a.m. every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday through Sept. 23 (no program on July 4 or Labor Day). The program is free with paid admission, but a separate ticket is required.

Since the program promises to let guests be part of a genuine process of discovery, there’s no telling what you might see or do on any given day.

Leave a Reply