Every apprentice shoemaker works his or her way through the same innocuous cardboard box. Printed on one side are the words “Protect from Freezing.” Inside, it’s filled with pieces of old shoes that date to the late 18th century.

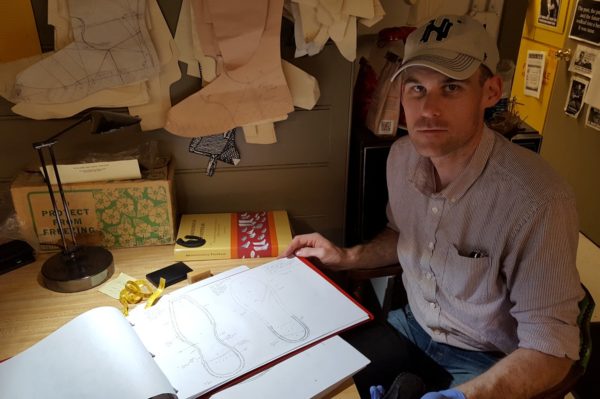

Al Saguto, the Master of the Shop, has been using the box as a teaching device for years. This month it’s apprentice Rob Welch’s turn to draw the ancient footwear and earn a step forward on the path to journeyman shoemaker.

The box contains about 20 shoe parts, some more complete than others. Rob’s task is to draw each piece in meticulous detail, determining as he goes which pieces might have come from the same shoe.

Rob pulls out a large binder that holds 11-by-17-inch paper, large enough to accommodate the outline of one or more shoes.

Pertinent source information is written at the top of each page. Below his name and the date, Rob copies what is known: “Old Philadelphia Collection; I-95 at Market and Vine; 1760-1800 (older pieces)… June 1978.” It’s hard to square with a present-day map, but this trove was allegedly unearthed where a highway ramp was being constructed in the 1970s.

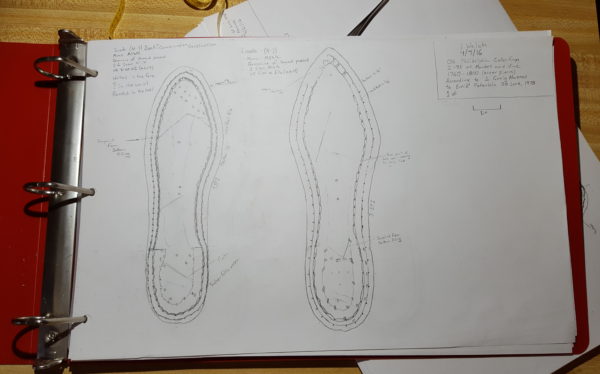

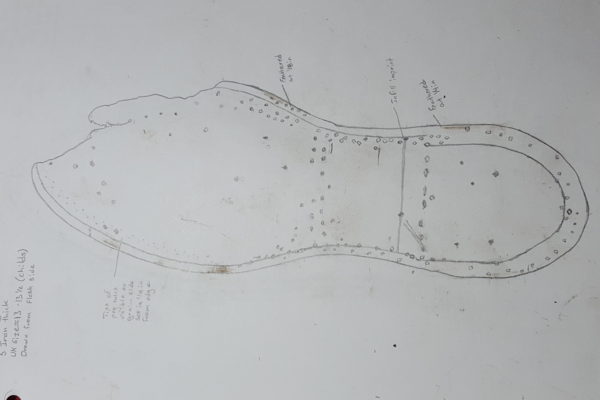

He lays a largely intact sole of a shoe on the paper and carefully traces its outline. “I draw from the side that has the most information on it, but as if the piece is transparent, so you’re noting all information on all sides.”

He proceeds to mark each individual characteristic in a vernacular that holds only the faintest meaning for me: channel, thread, feather, holdfast, stitch-holes, peg holes. Each distinct piece of information is measured and gets its own mark.

Many of the pieces, even the soles, are incomplete. Rob draws them exactly as they are. If they need to extrapolate to know what a completed shoe might have looked like, that can come later. For now, this is about precision, not imagination.

The process of close examination is a true education. Rob is learning the technical process 18th-century shoemakers followed, of course, but also where they used higher or lower quality leather, where they took shortcuts, and where they did great work (or not).

This, to be sure, is how our shoemakers can be certain that what they are making in the small shop next to the weavers on Duke of Gloucester St. is faithfully replicating the practices of old.

The shoemakers are also learning something about foot pathology. After examining thousands of shoes over the course of decades, they’ve accumulated raw data on issues addressed by shoemakers and wear patterns, not to mention just how big people’s feet really were 200 years ago. Here Al points out that you have to account for the ravages of time. Unless it happened to be dropped in a body of water, where the anaerobic environment preserved them, the leather has likely shrunk. “Underwater is where all the cool shoes are,” says Al.

“You can always get the most accurate information from a shoe when it’s soaking wet. As soon as it air dries, it starts to shrink, curl, and get brittle. When you can’t lay it flat and trace it anymore, you start to lose a lot of diagnostic detail.” His own experience suggests that dried-out pieces shrink about 7%.

Olaf Goubitz, a Dutch expert in the history of footwear, coined the term “calceology” in the 1980s to describe the practice. It evolved over time from an effort to determine the most efficient way to record information about shoes. Drawing them turned out to be much more useful than marking boxes on a checklist, writing a description, or building a database.

Rob says it’s also better than a photograph-or, to be more precise, many photographs-because a drawing can capture the details from every angle. “By drawing it you can get all of the nitty-gritty more effectively than the photograph can,” he says.

Calceology is a type of historical archaeology, seeking to understand not only the structure and assembly of shoes, but also new information about 18th-century society and culture. When contextualized with evidence found in written and artistic works, the shoes can affirm or refute our notions of what people wore, and yield new insights into the way people actually lived.

Al says Colonial Williamsburg is one of the only places in the world where people are regularly practicing this method of research today. It requires a certain type of mission and substantial institutional support. He ticks off a small number of other places where this kind of study is done today: one in the U.K., one in Switzerland, another in France. “Besides, who else has the specialized knowledge to do this?” he asks.

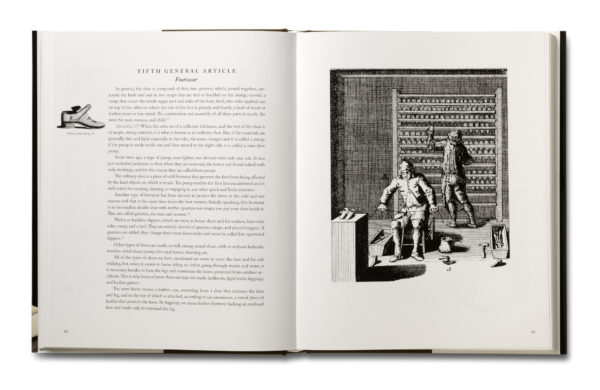

But the idea of illustrating the construction of shoes wasn’t a 20th-century invention, says Al. A 1667 publication from Amsterdam-Balduinus de Calceo Antique et Negronius de Caliga Veterum, if you really have to know—featured footwear that ranged from ancient Roman sandals to 17th-century shoes. At least one shoemaker in New York owned a 1760 edition.

In the 1770s, Hobey, one of the most affluent shoemakers in London, had a museum of antique shoes. At least a dozen texts from the 18th century were dedicated to the art of making a shoe, including one—M. de Garsault’s Art of the Shoemaker—which Al published an annotated translation of a few years ago. (It’s a magnificent book, by the way-that’s a sample page above.)

Colonial Williamsburg has in its collections somewhere between 500 and 800 shoes made, owned, or worn in Williamsburg. The uncertainty of the exact number comes from the fact that there are many pieces that may or may not be parts of the same shoe. A secondary collection lacking a Williamsburg connection has approximately another thousand shoes that date from 1670-1800.

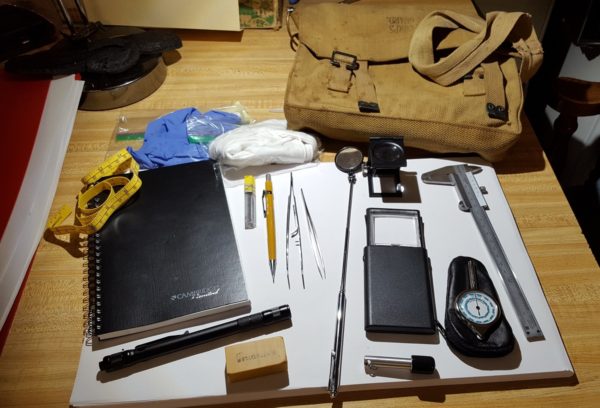

It turns out that our shoemakers have their own specialized toolkits for studying shoes. “Sometimes we get competitive about the gear in our kit,” says Rob as he pulls his tools out from a very cool messenger-style bag.

He lays out the contents on the table. There are two kinds of gloves, cotton and nitrile. There’s a notebook, a mechanical pencil with refills, and an art eraser. Rob prefers stout, soft leads that make a nice dark imprint. (Pens are not typically permitted on visits to archives and museum collections.)

Measuring tools include a caliper, a measuring tape marked in both inches and English shoe sizes, and a map-reading tool to measure actual length when there isn’t a straight line, such as around the outside of a shoe.

A fine-pointed tweezer and angled forceps make it easy to pick up objects for close examination. There’s also a magnifier and a magnet to detect nails. A small retractable mirror can be used with the flashlight to examine the insides of intact shoes.

Let’s return to the box where we started. Why exactly does Al direct his apprentice shoemakers to draw the same pile of shoes?

Apprentices have the opportunity to practice their methodology and hone their skills in handling artifacts under forgiving conditions. They can get a feel for the material and how to handle it. By gaining familiarity with the process, they can be confident in their ability to represent Colonial Williamsburg and their profession when they visit another archive or collection.

Rob will fit the tasks like drawing shoes around the core responsibilities in the shop, such as having conversations about the craft with visitors. They make the shoes they wear while working in the shop. Rob completed his first pair of shoes in February and is working on a second pair now. He has also made slippers for himself and two of the blacksmiths. And, of course, he assisted on others.

Rob’s apprenticeship, during which he has to pass five levels, should take about six years to complete. Then he will join Brett and Val as journeymen in the shop. The process bears some similarities to the historic rite of passage. But as Al says, “We’re teaching folks a lot more than they would have learned in the 18th century.”

Several years ago we stayed at a B&B in Hot Spring, Arkansas. The hostess showed us a little door halfway up the stairway. Inside were piles and piles of old shoes. It seemed that the original owners (a hundred years ago) had just tossed their old shoes into this small storeroom. It was so interesting to think of all of those shoes and their former owners and the lives they had led all those years ago.

If these shoes could talk, what stories they would tell!

Thanks so much for answering the question. My class often wondered if George Washington ever had to tie his shoes.

Thomas Jefferson was the first US president to wear shoe laces!

I wonder if Adams was the last to wear buckles…

Were laces on shoes at all common among 18th Century colonists in North America? It’s been a nagging question of my class for months. Thanks.

Hi Harvey

Shoe laces on men’s shoes went out of fashion in the 1660s (and in the early 18th century for women’s shoes) with the introduction of shoe buckles. By the 1790s the buckle fad had passed and laces returned to prominence. During the 18th century laces or ties were used by those who could not afford buckles (the very lowest members of society) or occasionally on more worn out shoes where the buckles straps had deteriorated. In either case, the shoes would originally have been made to close with buckles.

Thanks you for your question,

The Shoemakers