Lynn Zelesnikar plies her trade in the relative anonymity of an upstairs room behind the Silversmith Shop. Leaning over a small stand in the middle of a crowded desk, she is performing surgery on a minuscule piece of silver, carving in someone’s initials. This is the exacting work of hand engraving, an art that has become dramatically underappreciated—and undervalued—in this age of machines.

In a perfect world, everyone would understand the difference between machine and hand engraving. This is not a perfect world, so I ask Lynn to lay it out for me.

Machine engraving, she explains, creates a wake. “It’s like pushing a boat through water.” Colonial Williamsburg does a large volume of machine engraving using multiple pieces of equipment. Some machines are decades old and are used for particular types of work, such as name tags. The newest uses computerized templates and a diamond tip to create a design. That’s Donna in the picture above. She’s been working the pantograph and other engraving machines for 25 years.

But years down the road, especially after repeated cleaning or polishing, the metal can eventually become smoothed out again, making the engraving appear to fade over time. The trench created by the machine simply fills back in.

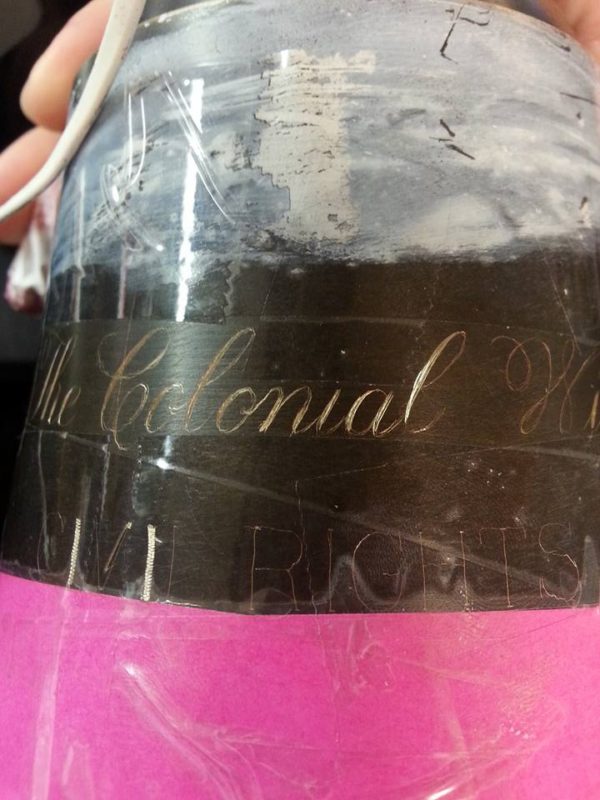

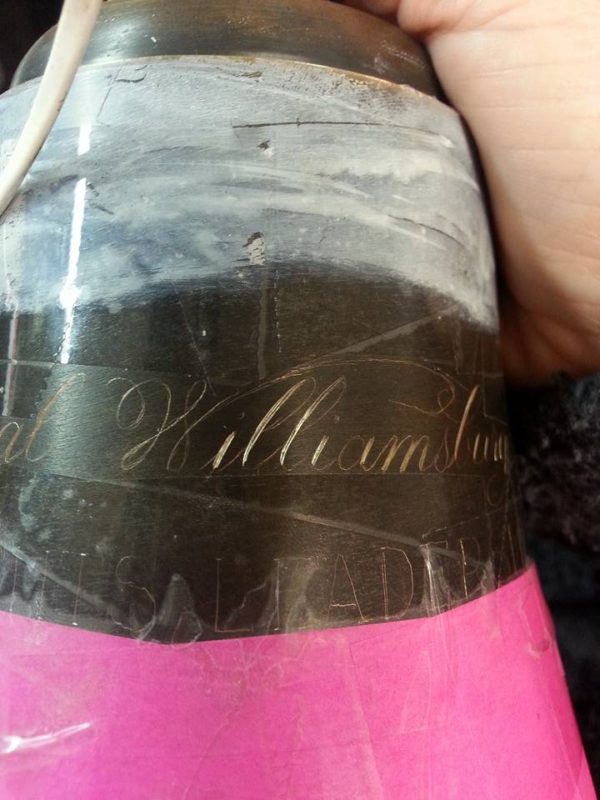

In contrast, when a hand engraver is painstakingly carving a design, he or she completely removes the small pieces of metal as they go. (Meredith, apprentice engraver, is doing that to the pitcher above.) Decades, even centuries, later, the engraving will likely look as good as the day it was made. Lynn attests to the enduring quality of the engraved 18th-century pieces in our collections.

Therein lies the difference between a souvenir and an heirloom. Not that there’s anything wrong with machine engraving. It requires experience, judgment, and an artistic eye.

Unlike her costumed colleagues engaging visitors in shops across the Historic Area, this Master Engraver works with two colleagues in a less hectic environment.

“Even though we’re not in front of the public, we’re still carrying on a tradition that was very much alive in the 18th century,” says Lynn. “And aside from these modern lights and some air conditioning now and again, very little has changed. These are the same tools used when Paul Revere was doing some engraving.”

The tools of her trade are like the stash of a mad collector of miniature screwdrivers. While those seldom used hang neatly in a round rack, perhaps 20 others—the favored ones—are scattered across Lynn’s desk.

The tools are just pieces of sharpened steel fastened to a wooden handle, but each one is unique. Most were custom-made to make a cut with a particular angle, thickness, or effect. The handles are short enough for Lynn to brace them against her palm as she works.

They are personal objects because each one has to feel right in the hand for the work to come out well. She mentions that she had to have new handles put on the tools she inherited from the previous master simply because his hands were larger, making the grip uncertain. Heidi, a Journeyman Toolmaker, made many of the handles.

Most modern hand engravers use air-assisted tools. Pneumatic tools are great for a lot of styles of engravings, things like steel and gun work, for example. “They’re also using intense magnification, like microscopes,” says Lynn. “We don’t use any of that in here. We try to do it as old-school as we can.”

Each engraving begins as a drawing. If it’s an unfamiliar pattern or image, Lynn makes a pen and ink sketch at the correct scale to capture the appropriate level of detail. For example, she drew the Raleigh Tavern for a bell. Currently she’s adapting a rococo pattern from an oblong 18th-century object for a square tea caddy. Since the object being engraved is shaped so differently, the result will not be an exact replica, but it will capture the essence of the original design.

Hand-drawing is often necessary even for a machine engraving. Lynn explains that they get a lot of artwork, such as the carriage above, that has to be translated. “You have to use a line or a series of lines to create an illusion” in order for the computer to be able to produce a template true to the spirit of the image. Unnecessary detail often needs to be removed so that the engraving doesn’t turn out blurry.

If it’s a small piece, the engravers have various ways to secure it in place, including a small stand. Recently they began using heated thermal plastic to hold items on the stand.

Here’s where it gets interesting. Lynn covers section of the object being engraved with a thin film of white watercolor paint, over which she draws the design freehand with a scribing tool (although she frequently uses a rose thorn from one of the bushes outside the office). If she messes up, she just smears the error away. Once she is satisfied with the drawing, she uses a scribe—just a sharp piece of steel—to make a more permanent mark in the metal. This is the first pass of actual engraving.

Then it’s on to whatever custom tools will be most effective in creating the design in all its contour and depth. Lynn puts a little grease or oil on whatever hand tool she’ll be using. As she cuts into the metal, little burrs are raised which have to be brushed away.

Since each design is individually drawn and engraved, each piece stands as a distinct bit of artistry.

Lynn adjusts her touch according to the material with which she is working. Copper tends to be “sticky;” sand-cast materials like brass or pewter feel gritty; white gold, because of its nickel content, is “hard as a brick.”

Lynn looks for inspiration in both our own collections and printed sources from the 18th century. A 1777 book, Bowle’s New and Complete Book of Cyphers, has been a useful source for designs.

The engravers work on objects of all shapes and sizes: from charms, rings, and other jewelry to silverware, cups, and pitchers to boxes and trays. They engrave monograms, family crests, scrollwork, cartouches, and more.

Hand engravers are a distinctly rare breed. When Lynn’s apprentice engraver Meredith completes her training in just a few months, she will be certified by Virginia—and only the fourth one in the state, joining Lynn and two others.

Lynn and her colleagues pride themselves on a quick turnaround. Usually, if you purchase a piece in a Colonial Williamsburg shop before noon, it can be hand or machine engraved by the end of the day. You can review options for designs, monograms, and more in the store, and they take care of the details.

If you’d just like to see how hand engraving works, visit the silversmiths, who can show you the basics. Many pieces are for sale at the Golden Ball or Prentis Store.

And they’re happy to engrave pieces acquired elsewhere. You can inquire by emailing engravingshop@cwf.org and they’ll be able to give you a price estimate. You can view some examples and get additional details on our engraving information pages. As long as it’s something they can draw and cut, they’d love to turn one of your souvenirs into an heirloom.

Congrats to Meredith soon to be one of four hand engravers in the state of Virginia. Mom and Dad are very proud of the work you have done. Good Luck it the future. Quarters

A few years ago my wife purchased a pair of cuff links, engraved with my initials, for our anniversary. A gift I will forever hold dearly.,As always, Colonial Williamsburg - a class act and a true jewel in the crown of America! ( forgive the royal reference)

We just returned home to PA after spending a week in Colonial Williamsburg. On a previous visit, a few years ago, my husband had bought me a silver ring in The a Golden Ball, that was engraved with my initial. The letter was wearing off and it was scratched. The day before we were to leave for home, it dawned on me to ask if it could be reengraved and shined. It could! And it would be done the next day by 12:30. The next morning we checked out of our accommodations and were even able to enjoy A Public Audience with Thomas Jefferson at the Charlton Stage before we picked up my ring. It was now hand engraved and it looks beautiful. I am constantly amazed at the talent in Colonial Williamsburg. It is such a remarkable place. I enjoyed reading this article and now whenever I look at my treasure,I can picture the artists, the special tools, the skill required to make it and it feels even more special. Thank you!

This was so interesting. I never thought you do such intricate designs In the 18th century manner.

Very grateful to the engravers for restoring my initials on a favorite earring last month!!!