Love is a powerful emotion. It can build us up, and tear us apart. Love is universally experienced in many forms, and many ways. I genuinely believe this emotion influences how we perceive history. Time and time again, love (or a lack thereof) has affected the choices people make. In this way, we are connected through time and space to those we will never know.

I keep this in mind every time I come to work, as it applies so specifically to what I do. My career at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation allows me to interpret the life of one woman who lived here. Her name was Hannah Powell. Portraying Hannah every day requires that I jump into her skin and try to understand her life, and the choices she made. This requires time and effort on my part; I have spent the past 12 months researching everything I can find about her.

Not only do I portray Hannah at an age when she is just about to be married and become a new wife, but I myself was engaged and married this last year. The day that Chris, my now husband, proposed to me was one of the happiest of my life. We both met while working for Colonial Williamsburg, and the courtship took off from there. We chose to get married on November 14, 2015 exactly one day and 239 years apart from Hannah Powell and William Drew’s wedding in 1776.

Photograph of Chris and me in front of the Governor’s Palace, where we first met

As Chris and I began preparing for our wedding, I thought more intently about Hannah’s. What would she have experienced? How did her love for William Drew impact how she saw her wedding? Unfortunately, I have no first-hand accounts of this event, other than a brief post in The Virginia Gazette. I don’t know what she wore. I have a limited idea of who was invited. But portraying this woman requires that I do know when talking to guests. So I started to pull from my own life. Based on my love for Chris, and what I know generally about 18th-century weddings, what factors were comparable? And which were not?

A photo of us posing with Hank, renowned canine visitor of Colonial Williamsburg

First, I can say that announcing a marriage was important, just as much in the 18th century as it is today. Nowadays, we use social medial, text messages, creative photographs, and phone calls to tell everyone of our joy. And, if you are traditional like Chris and me (I won’t deny we’re not), for your wedding you will send out formal invitations to request the presence of your nearest and dearest friend on your big day.

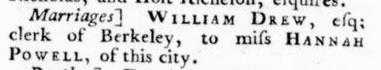

In Williamsburg circa 1776, you typically saw wedding announcements in one of three The Virginia Gazettes that were available. You would also read the banns in your family parish if you weren’t getting a marriage license at the county court. Reading the banns was fairly common in Virginia. Essentially, it assured both parties were capable of being married. No previous marriages, everyone over the age 21 or parental permission, no parties too closely related by blood, etc. The marriage banns had to be prominently posted or read three consecutive Sundays in your parish from the lectern. If both parties involved came from different parishes, they had to be posted or read in both places. Obviously, you can see how public wedding announcements could be. From what we know, it seems likely that Hannah and William had their wedding banns read in addition to their marriage announcement.

Marriage announcement in Alexander Purdie’s ‘Virginia Gazette,’ November 15,1776

Just like Hannah and William, Chris and I were also married in the Church of England (known as the Episcopal Church today). As an interpreter, this provided a very interesting parallel for me. I started reviewing the 1771 Book of Common Prayer with the modern version to see how exactly the ceremonies were different. While the wording is different, the form and intent are extraordinarily similar. The 18th-century version has the Ministry of the Word and the Blessing of the Marriage at slightly different locations. It also includes Psalms and a list of matrimonial duties to be read in the ceremony. Additionally, the man does not receive a ring. However, the address at the beginning of the ceremony and the words said that actually sanctify The Marriage are analogous.

The beginning of our ceremony in my family church

I also looked at where a ceremony would be held. In 18th-century Virginia, most occurred within the home of the bride. Weddings in a church could occur, but simply were not as common. In 1720, Reverend Hugh Jones, a Professor of Mathematics at the College of William & Mary, wrote with some frustration that:

“In houses there is occasion…to baptize children…In houses they most commonly marry, without regard to the time of day or season of the year.” ¹

Another example of a marriage at home occurred at Blandfield, the plantation of Robert Beverly. The marriage between his daughter, Maria, and Richard Randolph, Jr. of Curles was a well-celebrated one. As noted by Robert Hunter Jr., a merchant from London:

[Thursday, December 1, 1785] “…We arrived at Mr. Beverly’s at one o’clock, and were fortunate in finding the ceremony was not begun, as we understood it was to have been at twelve. About two the company became very much crowded. We were then shown into the drawing room and there had the pleasure of seeing Miss Beverly and Mr. Randolph joined together in holy matrimony.” ²

Given the tradition of the time, it seems that Hannah Powell and William Drew could have been married in the Powell House, just behind the Capitol Building. Chris and I had discussed being married in my family home. However, upon discovering how many people might attend, we thought it ill advised. Instead, we chose to be married in my family church by my family priest (who has known me since I was just a toddler). Although our weddings possibly diverge on the type of location, I can imagine the connection to family and church was as strong for Hannah as it was for me.

The Powell House, childhood home of Hannah Powell

In particular, one unique parallel between our weddings was the time of year. In Virginia, weddings often happen in December and January during the twelve days of Christmas. George and Martha Washington were married on January 6, 1759. Thomas and Martha Jefferson were married on January 1, 1772. However, Hannah and William chose to marry directly before Advent. The reason is a religious one. Advent starts on the fourth Sunday before Christmas and lasts through Christmas Eve, or December 24. It is a time for piety and reflection in the Church of England; to this day you are traditionally not supposed to get married during this season. Hannah and William therefore were married November 15, 1776. Chris and I picked Saturday, November 14, 2015 for a similar reason.

An image of marriage from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection (Detail from “The Stages of Man,” Artist unknown, ca. 1815)

While I speak about love and marriage, this is not to exclude or discredit the fact that they were not always synonymous in the 18th century. Although love is an emotion celebrated more regularly in the latter half of the 18th century, it was not the only qualifier for marriage at this time. In 1796, John Lloyd wrote about this in a letter to his nephew and ward:

“I would not have you marry a person for whom you had not sincere regard, because she had money – neither would I have you marry one unless she possessed some means of contributing to your mutual wants, unless, you were in a more independent situation than you now are…be assured of the worth of the old adage that when Poverty comes in at the door, Love flies out the window” ³

Certainly this is something for me to factor into understanding Hannah’s wedding versus my own. Love and suitability are intertwined when it comes to 18th-century marriage. This element informs how love is expressed, felt, and factored into marriage, and I cannot ignore it.

While I cannot say exactly what Hannah felt for her husband, I have clues through the primary sources to say the couple did have a happy marriage. From the extant documents, they appear to have had a courtship that was extended over six years across long distances. They endured hardship together during the Revolutionary War: William was clerk for the VA senate as they were being chased all throughout Virginia by the British in 1781. William Drew also writes about her in his will with extraordinary tenderness. It seems, by all accounts, one could make a strong case that they did care for each other.

There are dozens of other similarities and differences I could address between our weddings; it would probably take me an entire book to write about them. But every time I talk about marriage, every moment I spend speaking or writing about Hannah’s wedding, I am inevitably thinking about my own. It is difficult for me not to. I love my husband. I loved our ceremony. This love inspires me to interpret Hannah and her wedding the way I do.

My job is complicated. How do I respectfully interpret the life of someone whom I have never met? It’s very strange to have to live the life of someone else at work, while simultaneously living my own. However, what I am trying to do is create a very personal experience for those who meet me when I’m portraying Hannah. I’m trying to tell her story. When primary sources are not available, I pull from the shared human experiences of life in a way that is historically respectful. I am lucky that elements of my wedding were so similar to Hannah’s.

I think this comparison between our weddings is significant. It’s important that history be relatable-history is shaped by people, not by dates, not by books. It’s shaped by people. Yes, by telling Hannah’s story, I am in some ways telling my own. We both cared about the men in our lives enough to want to be with them for eternity. But I think that’s a story people can relate to. It relates, in its own way, the idea that love is timeless.

¹ Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790. Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture; University of North Carolina Press, 1999. pp 69

² Being the Travel Diary and Observations of Robert Hunter, Jr., a Merchant of London. Ed. Louis B. Wright and Marion Tinling. San Marino: Huntington Library, 1943. pp 206-209

³John Lloyd to Richard Champion, 28 June 1796, John Lloyd Letterbook, South Carolina Library, University of South Carolina.

GUEST BLOGGER: NICOLE BROWN

Nicole Brown has worked for the Foundation since 2014. However, her love for history started when she was very little. Nicole works as an Actor Interpreter for the Foundation. Prior to that, she worked in the Sites Department (where she first met her husband). Her passions, aside from History, are Shakespeare, dogs, and the small assemblage of antique books that her husband has meticulously collected for her. Nicole is blessed not only in her Williamsburg Family, but also in having two adoring parents who are her biggest fans.

Ritch Rowles says

What a great blog! Enjoyed reading and learning about the comparisons of your life story to that of Hannah. Thank you for sharing!

Nicole Brown says

It is my pleasure to share my love of history with you. I am delighted that this blog could inspire some interest in this particular topic.

Thank you Nicole - I am a bit of a history buff and do quite a lot of genealogy. When I hear stories like the one you shared, I get excited and automatically want to know more. We will be in Williamsburg this Spring and hope to meet you should you be around. Again, your story was lovely and I wish you and your husband all the best!

Nicole Brown says

Dear Ms. Kurhsjrtz,

I appreciate your love for history and genealogy. It certainly is a combination of passion and historical analysis that enables us to make connections and learn more about those who came before us. I am delighted that I could facilitate interest in this particular topic! I look forward to hopefully meeting you on the street as Hannah Powell.

This is a beautiful story. I find Hannah was buried in Culpepper at Saint Stephens Episcopal at the age of 76. Is anything known about William’s death or if they had children?

Nicole Brown says

Dear Ms. Kurhajetz,

What a wonderful questions! Indeed, we do know about William’s death and their children. Hannah and William only had one child, a son named Benjamin (I would assume named after his Grandfather). William passes away very young (approximately age 37) in 1785. It appears that he knew his death was coming; he wrote his will in September, resigned his post as clerk for Berkeley Co in October, and did the same for the Virginia Senate in November. He passed away on December 20, 1785. Hannah never remarried after that. Unfortunately, it also appears from the research that she outlived her son, who probably passed away before 1802.