Susanna Stuart Fitzhugh Knox by John Hesselius, c.1770, Sothebys Auction lot 718 (She’s Virginian!)

It was around this time last week that an image in one of our blogs sparked a debate over the representation of a woman’s body. As an apprentice Milliner & Mantua-maker, the Making History team immediately reached out to me for historical perspective. I hope this explanation helps clarify why the image was indeed period correct in its representation. I’d also like to use this opportunity to initiate a discussion of the female body and how it was viewed in the 18th century versus today.

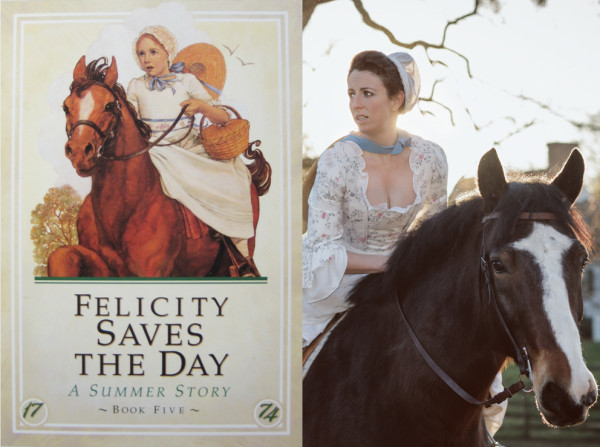

The image in question is the one below-an American Girl feature of employees reproducing the original covers of the Felicity book series.

“The one on the horse is showing a little much when you consider this is for little girls we should be teaching to cover, not show off…” - Brandy G.

Let’s start with a quote from one of Colonial Williamsburg’s favorite tutors, Philip Vickers Fithian, who provides us with a great deal of amusement and information on fashionable Williamsburg culture during the mid-1770s.

“She was pinched up rather too near in a long pair of new fashioned Stays, which, I think, are a Nusance both to us & themselves – For the late importation of Stays which are said to be now most fashionable in London, are produced upwards so high that we can have scarce any view at all of the Ladies Snowy Bosoms; & on the contrary, they are extended downwards so low that whenever Ladies who wear them, either young or old, have occasion to walk, the motion necessary for Walking, must, I think, cause a disagreeable Friction of some part of the body against the lower Edge of the Stays which is hard & unyielding – I imputed the Flush which was visible in her Face to her being swathed up Body & Soul & limbs together.” Phillip Vickers Fithian Private Journal and Letters July 1774, Williamsburg, VA.

The presentation and societal view of the “Ladies Snowy Bosom” in American culture has shifted alongside fashionable clothing throughout our history. Viewed as one of the most beautiful parts of the woman’s body, the presentation and visibility of the bosom and upper body of the female has not been without a great deal of controversy. Especially, if we view 18th-century culture through the lens of 21st-century mores.

Susannah Rose Lawson (Mrs. Gavin Lawson), 1770, John Hesselius, CWF, Acc No 1954-262, A&B

It is without a doubt that America is a very “body conservative” and private culture in comparison to our Western counter parts in Continental Europe. After declaring our Independence in the 18th century, we have quickly evolved into a unique and diverse society that is dissimilar from the countries where our ancestors originated.

In Scandinavian countries, like Sweden, for example, it is a common social practice to go to a sauna. Saunas are traditionally done in the nude, with a towel to sit on. My first time in Sweden and at a sauna, I was shocked by how comfortable all of my Swedish (and Finnish & Norwegian) friends were sitting in the nude with each other. I, being the American, was the odd one who was deeply uncomfortable with being privy to such intimate details.

This discomfort with exposing one’s body, is an interesting quirk of American culture, and it is my theory that the reason we are so uncomfortable is that we have a tendency to over-sexualize the body. In other countries, it’s just a body, and may or may not carry sexualized overtones. It simply depends on the situation.

Mary and Elizabeth Royall, c. 1758, John Singleton Copley, Public Collection

But back to the 18th century. At this point in time, western society seems to be a bit more comfortable with exposing that part of the female anatomy than we would be today (at least for modern average dress during the day, formal/cocktail dress and celebrity fashion aside). It is extraordinarily common for the bosom to be on display in 18th-century female dress. That part of the body was considered to be very beautiful, and celebrating and showing it off was normal.

Young children to adult women could reveal shockingly (for 21st-century views) low necklines in the 18th century depending on what was deemed fashionable. To have a wide and low neckline flatters almost every female body and helps encourage the hourglass-like silhouette that is traditionally deemed the most attractive female shape. By having a low and open neckline it helps give the illusion of a broader and fuller bust, which then, helps create the illusion of a more narrow waist. The final addition of a false rump or hoops, which enlarge the backside and hips of the woman, complete the look.

Elizabeth Boush (Later, Mrs. Champion Travis), 1769, John Durand, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Acc. No. 1982-271, A&B

Now, what is “appropriate” to wear in or around this low neckline depends. Traditionally, a woman would wear either a neck kerchief or “tucker”. A tucker is just a ruffle that goes around the neckline of the woman’s gown or jacket. It could be made out of a simple cotton, silk, or elaborate lace. It helps finish the look of the gown and would traditionally match the elbow ruffles, cap, and even apron that the woman would wear. This is what is called a “suit” in 18th-century millinery terms (not to be confused with a man’s suit which is a different thing).

Especially in formal or very fashionable situations, it was expected that a woman wear a tucker vs. a kerchief, since, at times the kerchief might be deemed too informal for that particular social situation. So the rules of when to wear a kerchief vs. a tucker would change whenever fashion changed—which was very quickly. A kerchief is a large piece of fabric cut in a square or triangular shape that is tucked into the neckline of the outfit or even worn over top, depending on the fashion and woman’s preference. They too could be made out of a variety of materials including linen, cotton, and silk. They could be white or different colors, printed or woven with designs, trimmed in lace, or quite plain. It was up to the individual woman. It is important to note, that they are regarded as a highly functional garment commonly worn by working women to help maintain cleanliness and a fashionable appearance.

Me modeling a newly finished silk gauze cap and wearing a cotton kerchief.

In the Millinery shop today, we prefer to wear our kerchiefs. First, they are common in fashionable and work-a-day dress. Second, we find when we do not, it is without fail that we will receive a comment or question that can potentially make a lot of people in the room (coworkers included), very uncomfortable.

This is, again, a reflection of modern American cultural mores, and not a representation of 18th-century views. We always try to use that moment to start an open and dynamic discussion of the female body, fashion, culture, and body image (something that I am very passionate about as a female of the millennial generation). While we often try to turn the question into a teachable moment, sometimes, it just makes everyone blush with embarrassment. So, we prefer to try and save everyone from that and wear our kerchiefs. However, we always clarify that it is our personal decisions to wear the kerchiefs and not because the low necklines were considered immoral in the 18th century because again, they were not.

N.B. Below are more images of American or British women and children. They have various necklines to help show some of the diversity that was around throughout the 18th century.

Slide Show Image Citations: Eunice Dennie Burr by John Singleton Copley, 1758-60, St. Louis Art Museum via WikiCommons; The Romps by William Redmore Biggs, 1790s, Leeds Museum and Galleries; Sophia Drake, c. 1784, by Ralph Earl, Private Collection via the-athenaeum.org; Her Royal Highness Princess Louisa Anne, c. 1750, British Museum, 1902,1011.2656; Mr. and Mrs. Isaac Winslow (Jemina Debuke) by John Singleton Copley, 1773, Public Collection (via artrenewal.org); Mrs. George Watson by John Singleton Copley, 1765, Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1991.189; Margaret “Peggy” Custis Wilson (Mrs. John Custis Wilson) by Charles Wilson Peale, 1791, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Acc. 2014-46,A&B; Elizabeth Allen Deas (Mrs. John Deas), 1759, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2012-91; Elizabeth Riddick Carr (Mrs. Samuel Carr) by John Durand, 1774, CWF, Acc. No. 1978-82, A&B; Louisa Airey Gilmor & Her Daughters, Jane and Elizabeth, by Charles Wilson Peale, 1788, CWF, 1967 - 364 A&B; Mary Orange Rothery (Mrs. Matthew Rothery) by John Durand, 1773,Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1991-150, A

Would this be the period that the phrase ‘best bib and tucker’ came from? If so - then what constituted the bib?

The bib would be the men’s best shirt and neckcloth. They didn’t wear narrow, modern ties, but rather wider thingamajigs that look like jabots, although I’m not sure that’s what they called them. Maybe that was called a bib, because it covered the chest?

Two things about necklines: some reenactors refer to a neck handkerchief as a “modesty piece” or “modesty cloth.” I’ve never seen this as an 18th century term. Have you? There is a modesty strip that is somewhat like a tucker — a horizontal ruffle of lace or fabric & lace that goes along the top of a stomacher.

The second thing, have you noticed that paintings don’t have a cleavage line, a crease were the breasts touch? Even Mrs. Charles Willing, with her formidable bosom, does not have a line. I think this was a fashionable ideal of the century, and perhaps the lace strip was meant to conceal it. Any thoughts on that?

Thank you!

From what I recall from a visit yo te Williamaburg millinary shop years ago:

The breasts arent on top of the stays (like a victorian corset) but inside them. the preference/what the stays did was to flatten them a bit, and hold them spread apart, creating/displaying a wide bosom being the look that was preferred. . Some of the dresses even seem to emphasize the width of the space between, unlike today when the ‘preferred’ look is to push all the fullness front and center and create a deep, narraow cleavage.

Abby, I recently purchased a caraco jacket and petticoat during my last visit. I was wondering if an ankle/just above the back of shoe was a good length for the petticoat. I’d like to do the jacket a touch longer in case I’d like to wear it a’ la Polonaise. Also I’d would like to know how deep the finished hems should be for both? Maybe hem lines would be a good next blog topic.

Your article was extremely informative, so that when I do wear my undress and all the trimmings during a future visit, I hope I will represent the period as true as possible.

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you! I can’t tell you how much time I spend thinking about my character’s neckline. (I write 18th C American romance.) Would they show it? Would they cover it up? One of my biggest issues has always been that a kerchief sounded way too informal for my more hoity toity characters. Now that I understand the difference between a tucker and a kerchief, I feel much better.

You’re welcome! I’m so happy to hear that you enjoyed the blog and it answered some questions! 🙂

Thank you so much for this article Abby! We were visiting Williamsburg at the beginning of December, and I recall very vividly that you did get into this discussion with someone who was in the shop the same time we were. I couldn’t help but be pleasantly surprised and happy that not only were you willing to discuss so much, but also to explain and educate folks as well as to an article of clothing that may seem small, but was incredibly important. I know this is part of what makes Williamsburg such a unique place to visit, but it has truly inspired me in my 18th c. costuming, and honestly, makes me wish I could win the lottery and move to Williamsburg and be an interpreter full-time. Thank you again for sharing your art!

Thank you so much, Mariah! That is a wonderful compliment, and I am really touched that you even remember me let alone specifics about my interpretation. I am so glad you enjoyed the piece & I look forward to seeing you again in Williamsburg! 🙂

Thank you, Abby for a very interesting post! I remember reading somewhere that the upper arms and elbows of a colonial woman were always covered because that was the part of a woman’s body, that if exposed would be considered scandalous. Is this true??

Hi Heidi,

Thank you for the feedback! I’m glad you enjoyed the post. To answer your question, as briefly as possible, we think that the origin of that idea of the “sexy elbow” comes from a memoir of a French woman who was at the court of Louis XVI (who was a very conservative Catholic and had published books on raising good Jesuit children during the 18th century) during the early 1800s. In the memoir she is reflecting back on this subject of elbows and sleeve length in regards to women’s dress. When you compare 18th century 3/4 sleeves to the short sleeves of the early 1800s - it could make sense that *maybe* that that is how the woman interpreted the short sleeve vs. “long” sleeve (sexy vs. not). This book was heavily republished in the late 19th century, and so we also don’t know how much “editing” happened of this woman’s memoir. (Note: I want to give credit to Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell who wrote “Fashion Victims” - she was the one who found the original reference and I just went further down that rabbit hole.)

As for period primary sources written in the 18th-century about the 18th-century- I’ve never come across any sort of documentation regarding the elbow as a erogenous body part. I asked Janea, the Mistress of the shop, and a few years ago a memo was sent out to our historians and curators inquiring if they had come across any mention of this subject as well, and no one had found any documentation giving legitimacy to the “sexy elbow”. I hope this helps answer your question! 🙂

Thanks, Abby for your excellent answer! I guess we’ll never completely know if elbows were considered sexy or not, but I find the changes in women’s fashions so fascinating. You all are so knowledgable and I appreciate the time you took to “uncover” the elbow mystery for me! ?

If my memory serves there are contemporary images of women at household tasks with their sleeves pushed well above the elbow. Mixing/kneading bread dough and laundry come immediately to mind. The “fashion” was to have the sleeves cover the elbows, but “necessity” said that the sleeves would get in the way of the task, or get soiled/wet/floured. For the duration of the task, “necessity” won over “fashion”. I think there was a greater conceptual distance between what was acceptable/done in one’s own home, or on one’s own property, and what was acceptable “abroad” - in a more public place. “Violations” ( I use the term facetiously here) would have been thought “unusual” not “Shocking!”.

Thank you so much for such a interesting topic for the blog. In one visit to Williamsburg, I recall being surprised at learning from an interpreter the attention paid to a man’s calf during that time period and how important is was for a man to have a well formed calf. That would make a very interesting blog as well.

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed the post!

Thanks for a thoroughly enjoyable article which was very well written and instructional. I look forward to more posts such as this one.

Thank you so much Bella! I am sure there will be more in the future! 🙂

Nice piece, Abby…you ladies keep uu so well informed…and inspired by the great work you do!

Thanks Pam! 🙂

I honestly don’t understand why anyone would be rude enough to make comments on your cleavage in a period outfit. Has no one a sense of history anymore? Hell, even some Victorian fashions had a lot of cleavage to them. The 1870s showed a lot of neckline and chest and were almost a throwback to the 1700s in the fashion trends. but really…

I’d love your input as to whether higher collars (ruched, etc.) were more prevalent in the South, and/or as time went on. Just wrote at chapter (in “Locating American Art”) referring to women’s costume around 1807-9 concerning two sisters-in-law (one living in Natchez, MS the other in Boston) that contrasted their décolletage. Thanks! -Kimberlee

See: Judith Sargent Murray, Gilbert Stuart, ca. 1807 https://www.pinterest.com/pin/560979697306234732/

versus: Mary McIntosh Sargent, Gilbert Stuart & James Frothingham, ca. 1807 http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-r3iSK4hFrnk/Ub9g5s40TdI/AAAAAAAAAKM/hs7lzUt1RJM/s1600/IMG_0899.JPG

Sorry about the quality of the photos!

Hi Kimberlee!

Can you forward this question to millineryshop@cwf.org? Thanks!

Abby:

Beautifully written and clearly explained. Keep tip the great work!

Thank you! 🙂

First time to this blog and loved this post! 🙂 Thank you so much for posting! Learning something new every day!

Welcome to the blog & I’m glad you enjoyed the post! 🙂

Thanks so much for this wonderful post, Abby. I especially love the images, and your point about how difficult it is to look at the 18th century without the filter of our 21st century cultural norms. It’s very difficult in any time period to know what’s appropriate for which situations. Today, showing one’s cleavage seems to be perfectly fine, even in school and work situations. I find this a little disconcerting because I didn’t grow up with that being the norm. So trying to figure out what was proper in which situations in 1775 or thereabouts is even trickier! (Wearing hats indoors is a similar quandary, I find, both then and now.) The other difference I see is that today exposing one’s “cleavage” seems to be what it’s all about. Back then, it seemed to be more about the curves of a woman’s breasts as pushed up by her stays.

Being a word nerd and having done some limited research into 18th century terminology a few years ago (in period dictionaries and newpapers), I found that “handkerchief” was by far the most common word for the cloth that women wore around their necks. I hope this is helpful!

Keep up the terrific posts, and thanks.

Hi Ruth!

Thanks for the feedback and your contribution to this discussion! I’ve really enjoyed reading other people’s responses to how the view of the body has changed and their experiences around the world. I totally agree in the hat department - another fun little rabbit hole of research!

As for my use of the word kerchief vs. handkerchief - it mostly comes from the fact that I’ve come across so many variations on what they are called, like handkerchief, half handkerchief, neck handkerchief, kerchief etc, that I just shorten it to kerchief in my interpretation for the sake of ease of communication, and that was most definitely reflected in my writing of this post. I probably should have used handkerchief as it is more common, but kerchief is what I used. 🙂

Do you have a period reference that includes the term “kerchief” without “hand” preceding it?

In period text I’ve only seen “kerchief” used when “hand” as a separate word precedes it. Now I search I do find one “kerchief” listed in 1752 listed in the Proceedings of the old Bailey http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17520514-18&div=t17520514-18&terms=kerchief#highlight however, if you look at the original text you’ll see a very unclear something before the “kerchief” that is just the right amount of space for “hand” that very much resembles “hand”.

Hi Paul,

Here is one example of kerchief being used without the use of hand before: “The kerchief from her neck of snow would fall with freedom bold, and leave her bosom bare.” From The Blossoms of Helicon by W. Woty 1763, London.

So, with that, I would like to put to rest the discussion of terms, as I don’t feel this is the place to have this conversation. Also, if you wish to share this citation, which is fine, I ask that you credit the Margaret Hunter Millinery Shop for providing you with this source. Have a great day! 🙂

I can never get myself to use the word handkerchief in this context because, to me, this is something you blow your nose in. Don’t doubt that handkerchief is the right word, but…

I suppose it’s like any word that seems odd at first, Mary Jean. The more you use it in context, the more normal it seems. Perhaps you could say “neck handkerchief ” if that makes you more comfortable, because that was also common terminology of the period. 🙂

Very interesting, thank you!

You’re welcome! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

Abby, this was a wonderful post. Very informative in helping us understand the 18th century perspective on dress. It was fun to look at the artwork throughout this post and see ones with the tucker & kerchief and ones without. I always enjoy your posts. Thanks!

Thank you so much! I’m glad you enjoyed the post! 🙂

This is an excellent post, but I think you have missed one element that is contained in Philip Fithian’s quote above: his description of “snowy bosoms.” The 18th century ideal is of paleness, and as a result, and girls who were outside would have definitely worn a kerchief tucked into their neckline. All the images you show are of formal portraits of upper-class women, wearing formal dresses that would have been worn without a kerchief. If you look at prints of everyday life, most of the women have some sort of covering in order to prevent tan lines on their chests! That is what I object to most about the Felicity picture — if she were outside during the day in a Virginia summer she would definitely have covered up, not for modesty’s sake, but for sun protection.

Hi there; thank you for your comment. You are correct about the use of kerchiefs as a form of sun protection—indeed, it is a regular feature of our interpretation at the shop, and why I prefer to wear one. Yet, with all due respect, I believe you perhaps missed the larger point of the piece. The post emerged from a comment regarding the exposure of the body, and how we view the eighteenth-century body through the modern lens. My analysis—based upon significant archival and secondary research—examines that cultural difference from our ancestors, and uses it as an opportunity to elucidate fashion and the options women had at that time. So the accuracy of a children’s book cover (or its reproduction) falls outside the scope of this discussion. Thank you again for your interest in this post and my research!

Hi! What a wonderful and concise response to that comment. I work at a living history museum in New England and we also opt for kerchiefs most of the time for the very same reason. We still get the occaisonal inappropriate comment on our bodies and dress though, I would guess in part because of the novelty of the clothing and because of the overall cultural trend to sexualize women’s bodies. It’s a very difficult line to walk with people who are complete strangers and who are supposed to be your guests.

Thank you so much! I really appreciate your response and the camaraderie with your experience as an interpreter. <3 🙂

Excellent piece Abby!

It is very thorough and plainly states the facts of fashion, body image, and mores both 18th and current.

The images are lovely and a wonderful visual to understand the norm.

Thank you!

Thank you so much for your comment! I’m glad you enjoyed the images! I had fun collecting them all for the post! 🙂

I do wonder about all the religious groups of the time. Just like today, even though the majority of the population can dress what we call immodest and show cleavage. Wasn’t there others that would cover up on purpose?

Of course, Tammy! Society was unique and diverse in the 18th century, just like today, and there were religious groups, for example like the Quakers, who dressed a little differently according to their religious values. What I am really trying to express here is the over arching cultural “norm” of the 18th century and not try and break down subcultures or religious groups. 🙂

I was just thinking things haven’t changed too much have they 🙂

Great job, Abby!

Thanks, Susan!!

Abby, thank you for your post and for the collection of photos. I love to see examples of the dress. It is so true-the wide and low neckline is so flattering, especially with lovely lace around it. Question. Where did 18th century Williamsburg ladies get their lace? Were there lace makers in Williamsburg at the time? How much variety was available to them? How expensive was it? (Ok, that’s a bunch of questions!) I have heard that, for the earliest settlers in the colonies, lace-making was one of the few jobs where a woman could earn a living wage.

Hi Sam!

I’ll do my best to answer your questions, though the study of lace is not my strong point. So - here we go! Women in Williamsburg would be able to purchase lace from merchants and milliners throughout the city. It would have been imported from England to Virginia. For professional lacemakers in Williamsburg, as far as I am aware, there is no evidence of lacemaking being practiced as a trade. As for variety, it seems pretty endless, there was a variety of design and a range of prices. Some lace could be a bit more affordable while others were extremely expensive.

I hope this was helpful! 🙂

Great post, Abby! Such an interesting read and you did a great job of debunking the myths.

Conservative Americans should learn to be quiet - I think all the milliners should feel free to show some colonial cleavage. 🙂

Thanks, Katie!!! 😀

I don’t think that the point of this post was to tell more conservatively minded people to be quiet, but to make us all think a little more about the cultural context in which dress was created and worn, and how our modern perspective and attitudes can color our perception of the past.

No need for conservative or liberal Americans to be quiet! Having said that, I certainly do not object to the display of some colonial cleavage!

I agree with Katie. That being said, as an older woman, with an ample bosom, I find that if I appear in day attire without a kerchief, there are comments made. I was asked to appear as a woman of about 1770 or so in a ballgown. That I wore without kerchief. The modern ladies AND gentlemen were want to comment on my low neckline, rather than the elegance of the gown or my stunning stomacher! I laugh it off as the latest fashion in persona. But later when I changed into a modern evening gown, it was noted that roughly 245 years makes quite the difference in dress.

Actual historical knowledge for the win! 🙂 It’s also important to remember fashion differences in terms of regional geography. Felicity lived in Virginia, and down south the Puritan influence was much less marked even during the time period in which it flourished up north. And in terms of time, yes, people forget that fashion was a lot more revealing in the pre-Victorian era. I think the prevalence of popular Victorian stories and movies in our time makes it easy to lump all historical fiction into Victorian fashion and mores, but doing so would be incorrect.

Yes, it is always interesting to think about how the Victorian era and, what I call, the “Neo-Victorian” era of the early/mid 20th century has affected our modern views on society. Our immediate histories really have a strong hold on how we view the past.

Thank you for the positive feedback! 🙂

This was such an interesting read!

Thank you! 🙂

It’s an interesting point you make about American body modesty compared to other world cultures. I spent a summer in Japan some years ago, which like Scandinavia has a rich cultural tradition of communal bathing (onsen or hot spring bathing) wherein being naked in front complete strangers in this specific context does not have sexual connotations. It’s just taking a relaxing bath in super hot water. With other people doing the exact same thing, who do not care one bit how you look naked. It certainly took some getting used to, especially since preteen and teen culture in America tends to put a great deal of shame onto exposed female bodies (remember the horror of having to change in front of each other for gym? That’s culturally taught, not a natural aversion to seeing someone else’s naked body). I was in my early teens at the time and was still getting used to my own puberty-stricken body, so it was actually kind of reassuring to be in a situation where naked female bodies were no big deal and there was no sense of judgement or comparison.

So remember before you complain about how a low-cut neckline on a woman in historical dress means she’s “not a good role model,” consider that you might be encountering a different culture, one that isn’t as hairpin-trigger sensitive as ours about the potential sexuality of the female body. The past is indeed a foreign country, complete with different social rules, and is as alien-and simultaneously familiar-to us as the contemporary culture of Japan or Sweden. That was the point of the historical American Girls stories to begin with-that young girls could recognize that while some things about growing up as a girl in the past were completely different, a lot of other things like friendships, fights with siblings, and learning to take responsibility are exactly the same.

Thank you so much for sharing your experience in Japan! I can’t imagine being a young teenager and put into that situation - I would have been so embarrassed - it is awesome that you were able to use that as a confidence boost and took it as a reassuring moment. That is just awesome - high five!!! 😀

I beg to differ a little. My mom had little care about being naked in front of me and barged into my room when I was dressing sometimes to talk to me. She’d tell me to stop trying to hide because we’re both women and I didn’t have anything she didn’t have. I can’t stand the idea of changing in front of anyone and that has been that way since I was a little kid. Changing in the girls locker room forced me to do it in a shower where I’d actually have some privacy. Even then I got laughed at because I refused to change in front of the other girls.

It sounds like you have a personal hang-up with being seen naked or seeing others naked and if you’ve always been that way then it’s slightly different from the cultural body modesty I meant. Most little kids have zero problems with being naked around strangers or parading around in their underwear, or seeing others naked. Once they hit school age they’ve for the most part learned it’s not socially acceptable to show certain parts of their body or their underclothes to other people.

Rather unfair to state that Ehren has a “personal hang up” because she does not like someone invading her personal privacy with their nakedness or expecting her to be comfortable being naked.

That is a personal choice. She prefers not to show off her body to all and sundry. It does not mean she has any “hangup” or “repression” nor is she judging others who are comfortable with being naked in front of others. She has not “learnt” from someone else or “society” that is not acceptable to show off - she has a personal preference to not do so and that should be respected and not judged.

My friends and I spoke to Abby at length in the Millinery Shop in December. Fascinating discussion on cleavage now and then! Thanks for the great article! Talking with experts like Abby is the highlight of a visit to Williamsburg, and now with the blog.

Thank you so much Susan! I am so happy you enjoyed the blog and our conversations! 😀

Very well-written and informative post! Thank you for providing food for thought about changes in fashion and social mores over time.

Thank you for the positive feedback! I’m glad you enjoyed the post! 🙂

I thought, though I could very well be mistaken, that in Europe during this time, showing a bit of nipple was the fashionable thing to do. If so, it would make sense that America was also on the edge with fashion since I also thought they followed Paris fashions quite closely.

You definitely see it in portraiture, that is for sure! 🙂

Wow! Fantastic piece. I just learned that I have been using the term “tucker” wrong. I was under the impression it was slang for the kerchief. Thanks for such great information.

You’re welcome and thank you for the love! 🙂

Fantastic post!

It’s so important to look at fashions and body image in their own time, and to recognize when we are seeing things through our 21st century bias.

Thank you for your thoughtful post, and wonderful research and clarity!

Thank you!!!