This Sunday the Kimball Theatre will be showing The Howards of Virginia, a 1940 film starring Cary Grant… and Williamsburg. This is the story of how the first Hollywood production in the restored town came to be.

In September 1940 Nazi Germany was advancing, Britain was under bombardment, and the first peacetime conscription in American history was underway. Democracy itself seemed to be under siege. Against that backdrop came The Howards of Virginia, a celebration of the nation’s founding through the eyes of one family.

The movie’s timeliness was not lost on reviewers. “Seldom do the films illuminate our fundamental ideals with such simple and straightforward analysis,” said the New York Times. “It is propaganda,” said the New York World-Telegram, “but it is propaganda to give us new faith in those convictions and hopes we cherish in a world gone mad with terrorism and prejudice, hatred and intolerance.”

Sound familiar?

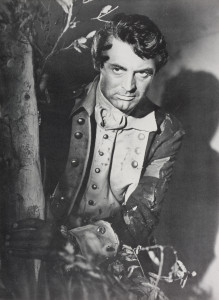

The film starred Cary Grant as Matt Howard, a man of the Virginia frontier whose relentless optimism and sense that he was just as good as anybody else fueled his rise in society at the time of the American Revolution.

It’s a classic American story. Howard works his way up in the world, marrying above his station and battling his nemesis. Along the way he shares the stage with Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and George Washington, and witnesses many of the key events leading up to the Revolution.

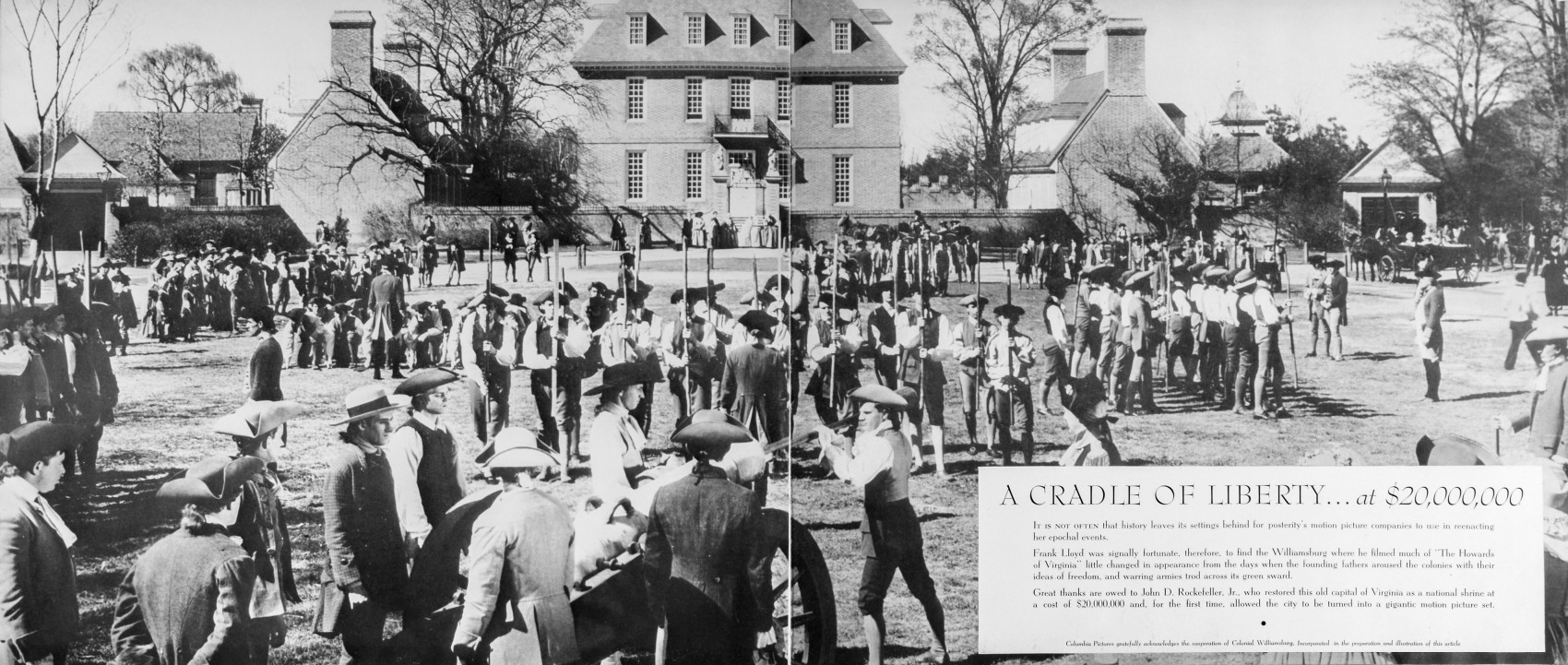

The movie, which boasted a $20 million dollar budget, was filmed in Williamsburg and on a Hollywood sound stage where exact copies of the town’s rooms were constructed.

How, you might wonder, did this happen? Funny story.

It started with a tree.

In early 1939 Columbia Pictures acquired the film rights to a recent novel by Elizabeth Page, The Tree of Liberty. Someone in their publicity department figured that planting an actual tree—in Atlantic City, N.J., of all places—would be a swell way to gin up some interest in the project.

And what better place to get a tree than from Williamsburg, the “cradle of American liberty”? After some initial resistance (“we must always be watchful lest the Restoration be exploited through commercial channels,” they cautioned) Williamsburg relented. They sent a live oak, about 12-feet tall, by train, where it was planted in a ceremony on May 5.

And what better place to get a tree than from Williamsburg, the “cradle of American liberty”? After some initial resistance (“we must always be watchful lest the Restoration be exploited through commercial channels,” they cautioned) Williamsburg relented. They sent a live oak, about 12-feet tall, by train, where it was planted in a ceremony on May 5.

But apparently a seed was planted as well, because a few months later a 54-page script outline appeared quite out of the blue in Williamsburg. At that point the film adaptation was still called The Tree of Liberty, but it was eventually given the title The Howards of Virginia. Getting over their initial surprise, the Restoration’s leadership started negotiating a collaboration with Frank Lloyd, the film’s producer and director.

The Glasgow-born Lloyd was an accomplished director, best known for Mutiny on the Bounty, which took the 1935 Academy Award for Best Picture. He visited Williamsburg that fall, and it was agreed that exterior shots would be filmed in Williamsburg, while interior scenes would be shot in rooms recreated in exacting detail on a Hollywood sound stage.

Reading The Tree of Liberty, Rutherfoord Goodwin was concerned about the book’s interpretation of the American Revolution. Page, he believed, was incorrectly characterizing the Revolution as a “war against privilege,” which was at odds with his own take, that it was a war against unjust taxation.

Either way it led to independence, but Goodwin was dubious about associating with what he construed as a “leftist” agenda. This was the 1930s, after all. Communism was still ascendant in the Soviet Union, and in the crisis years of the Great Depression many Americans were wondering if there wasn’t something to it. Page’s view of the Revolution, he wrote, was “the product of the left wing of the bird employed in the left hand of the author, possibly written in red ink.”

Yikes. It is worth noting that debates about the causes and consequences of the Revolution are just as alive today.

Colonial Williamsburg’s experts were enlisted to vet the script and help it come to life.

Historians critiqued details that led to improvements in the script. Mary Mordecai pointed out that frontier violence against white settlers had been caused in part by the slaying of friendly Cherokees, and that Tidewater planters were cartoonishly portrayed as pleasure-loving, indolent, and indifferent the fate of their colony.

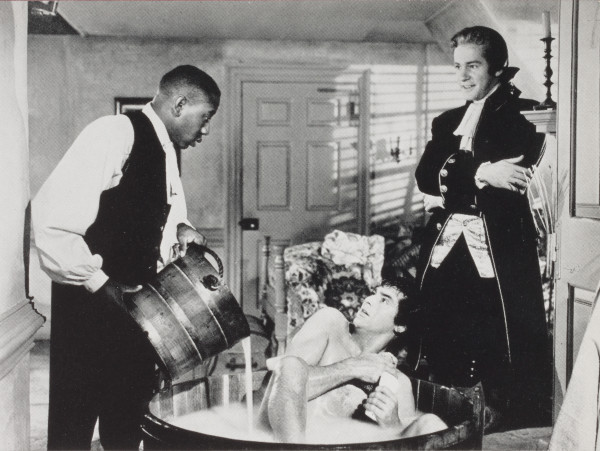

Architect A.E. Kendrew assembled blueprints for Williamsburg buildings so interiors could be recreated on a Hollywood sound set. The plans included the House of Burgesses and two committee rooms in the Capitol, the ballroom and supper room at the Governor’s Palace, and the Apollo Room at the Raleigh Tavern.

The moviemakers even asked the all-important question of what kind of tub Cary Grant should use in one of the more amusing scenes in the movie.

In early April 1940 director Frank Lloyd led an entourage to Williamsburg that included 15 train cars full of colonial coaches, costumes, guns and other accessories. Civic leaders and a crowd of curious townspeople greeted him. Columbia’s publicity people claimed 5000 people welcomed them at the train station, a very unlikely occurrence in a town of only 3500.

There was more hyperbole. Cary Grant may have been the “star stag” of William & Mary’s prom, but he certainly didn’t dance with “700 admiring coeds.” Nor did anything close to 100,000 people watch the filming. Still, having a big-budget Hollywood production in town, even for a week or two, was pretty big stuff.

Cast and crew also occupied 18 rooms at Brick House Tavern, 13 rooms at Market Square Tavern, and 10 rooms at the Williamsburg Inn. Lloyd and his family stayed at the Orrell House.

Few Colonial Williamsburg employees were able to participate in the filming directly. They couldn’t be spared from normal duties, although hostesses, as the female guides were known, were permitted to work on their off days. More than 500 people, primarily unemployed people and students at the College of William & Mary, earned $5 a day as extras.

Colonial Williamsburg’s president, Kenneth Chorley, viewed sample scenes in late June. He was “thrilled” with many scenes and especially pleased with Cary Grant in the leading role. But he was “shocked beyond words” about poorly rendered interiors in the Governor’s Palace and “Elm Hill” (which was actually Carter’s Grove). Redwood plywood had been used to simulate walnut paneling, and from Chorley’s perspective made the rooms look “absolutely unauthentic and… hardly recognizable.”

Lloyd tried to downplay the objections as a “tempest in a tea-pot,” but Chorley considered it a “grave error” that threatened to undermine Colonial Williamsburg’s growing reputation for accuracy and attention to detail.

But crisis was averted when Chorley traveled to Hollywood in July to view the rough cut. This was a better quality film, and the paneling that had appeared so questionable looked much better. “I feel the picture is marvelous in every way and that it does great credit to Williamsburg,” he wrote to Lloyd.

The Howards of Virginia had its national premiere on Sept. 4, 1940 at three Richmond movie theaters, followed by a Colonial Ball. Unfortunately Cary Grant was unable to make it since he was still busy filming Philadelphia Story. But his costar Martha Scott joined Frank Lloyd for festivities that began at William Byrd’s Westover Plantation and went on to Richmond.

The Williamsburg premiere was on September 20 on what they termed a “bicycle basis.” In this case that meant two showings at the Williamsburg Theatre around one at “the negro school” for an African American audience. Since there was only one copy of the film, the canisters would be shuttled to Bruton Heights School as the reels were finished.

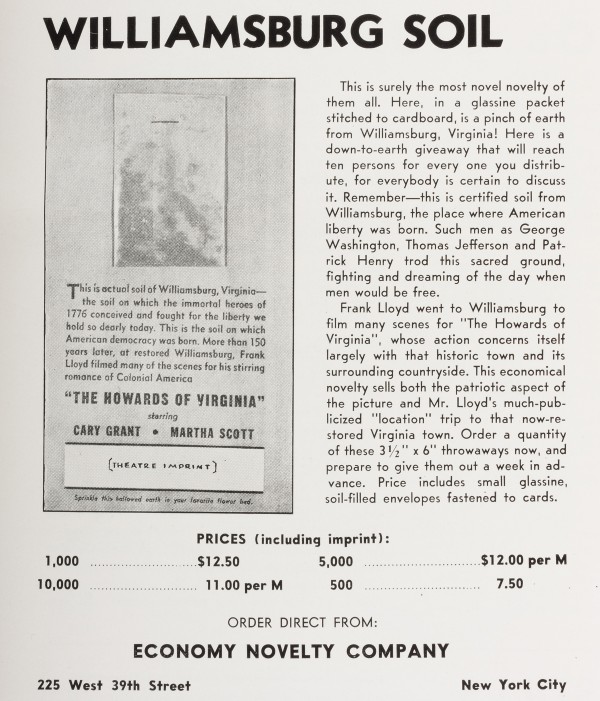

The movie inspired some humorous promotional ideas. The publicity book suggested dressing ushers in colonial garb, doing Revolution-era trivia questions, trying out Martha Scott’s colonial hairstyle, and giving away dirt—yes, dirt—from the colonial capital. The Economy Novelty Co. in New York purchased 200 lbs. of dirt to sell to theaters to use as a giveaway.

Hilariously, a theater in Junction, Kan. mistakenly requested 7500 lbs. of dirt to give away at showings of The Howards. The error was discovered as Colonial Williamsburg tried to figure out how to transport such a volume of premium Virginia clay. (By train, in barrels.) It was finally determined that they meant to order 75 or 100 lbs., and that much smaller amount was soon sent out by the maintenance department. There is apparently no record of whose backyard it might have come from.

The Howards of Virginia filled a certain need for reassurance and inspiration when it first appeared. In this age of terror and violence, it still works.

Many thanks to my colleagues in Colonial Williamsburg’s Archives Department for unearthing and sharing the records that made it possible to tell this story.

A movie with historical confirmation; after reading the aricle, which brings new insight to ‘modern’ history of Williamsburg ~ I need to see the film again. Delightful humor of ‘dirt’ being given away directly from Williamsburg. This shows there is always something new to learn about the history of Williamsburg.

Love this movie & it’s message still resonates today. There is a cost for our freedom.