In “Cry Witch,” a popular evening program that reenacts a 1706 witchcraft trial, the audience gets to decide the outcome. Here is the true story behind it.

It all started with the untimely deaths of some pigs and a failed cotton crop. In Pungo, a settlement a couple of miles from the Atlantic Ocean in what is now Virginia Beach, John and Jane Gisburne were convinced there had to be a reason for the bad luck.

There were whispers among the neighbors. Elizabeth Barnes said that she had seen Grace Sherwood pass through a crack in the door—or perhaps it was through the keyhole—like a black cat.

You couldn’t miss the symbolism. The neighbors thought Grace was practicing witchcraft. They were blaming her for their bad luck, but why? Was she odd, or different from them? Was it an old grudge turned malicious?

Grace and her husband James sued the neighbors for slander and defamation for spreading the rumors. They lost.

The year was 1698, and it was only the beginning of the trouble for the nearly 40-year old Grace. Once you started acquiring a reputation in a small community like Pungo, it could be hard to shake.

The Sherwoods started with a 50-acre farm that James inherited from his father. They brought up three sons, but little else is known about the family. James died in 1701.

Another incident led Grace to sue Luke and Elizabeth Hill for assault and battery in 1705. Elizabeth, she said, had “assaulted, bruised, maimed, and barbarously beat” her. This time she won damages amounting to 20 pounds sterling. Whatever the cause of the conflict, Grace’s satisfaction must have been short-lived because months later, the Hills openly accused her of witchcraft.

The belief that witches were actively causing trouble for neighbors and communities wasn’t confined to Salem, Massachusetts. The early modern world was a scary place. Darkness was forbidding, and the night kept most people indoors. Was the scratching sound that awoke you a tree branch in the wind, a wild animal, or something more sinister?

Accidents and misfortunes were an everyday reality, but in the age before the Age of Reason, many turned to superstition and the supernatural for explanations of illnesses, bad weather, financial setbacks, or whatever else had befallen them.

Virginia never had a wave of witchcraft allegations the way New England did. The accused were prosecuted under a 1604 English law “against conjurations enchantment and witchcraft.”

Joan Wright of Surry County was the first person known to be charged in Virginia. She was acquitted. Only one person—a man, no less—was convicted of the crime in 17th-century Virginia. His punishment was a whipping and banishment from the colony.

But now it was the 18th century. Would Grace fare any better?

After several delays, Grace complied with the court’s order that a jury of 12 women should examine her body for evidence that she was in league with the devil. They were looking for “witch’s marks,” irregularities or discolorations on the skin that would supposedly indicate where demons suckled.

Bad news for Grace. They found two spots, “blacker than the rest of her body.”

One can only imagine her reaction. She was undoubtedly past rolling her eyes. Could the certainty of her accusers, and perhaps the whispers all around, have aroused self-doubt?

The county court wasn’t sure what to do next, so they asked the attorney general for the colony to bring the charge against Sherwood at the General Court in Williamsburg. But he advised them to pursue the facts of the case a little further before taking that step.

Their next step was to take Grace into custody until she could post bond. Then the constable and the sheriff for Princess Anne County were sent to search her house, looking carefully “for all images and such like things as may any way strengthen the suspicion.” After searching her house, the county court finally decided to try “ducking” the accused witch.

Call it the “going medieval” option.

Ducking, a practice that had been largely abandoned in Europe, meant that Grace would be bound and submerged in a body of water, in this case the Lynnhaven River. If she floated, it was proof that she was a witch. If she sunk, it meant she was innocent.

The court record indicates that Grace consented to the ritual. One wonders just how enthusiastic she was about it.

The first attempt was postponed, “the weather being very rainy and bad so that possibly it might endanger her health.” That or the gentlemen of the court didn’t want to get mud on their shoes. Your call.

But July 10 was a swell day for a ducking, so off they went to the designated spot near William Harper’s plantation. Typically the subject of the ducking was stripped naked and cross bound, thumbs to opposite toes. A rope was fastened around her to ensure that she would not drown. Indeed, she must have escaped her ties because she began swimming.

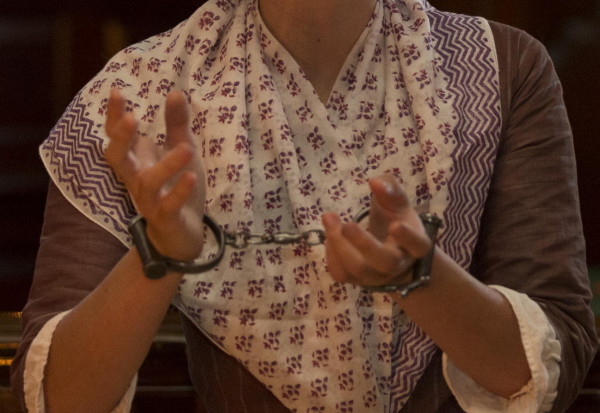

That was all the proof the assembled spectators needed. She had not sunk the way any upstanding person would, so she must be a witch. After enduring the humiliation of another search (surprise! the moles—or whatever—were still there), the sheriff placed her in irons and took her off to jail. The plan was to send her to the General Court in Williamsburg for further proceedings.

We don’t know how long she remained confined. Guesses range from several months to seven years. Nor do we know if there was ever a second trial. The records were among those burned during the Civil War. But she petitioned for the return of her property in 1714 and was granted the 144 acres she had inherited from her father in 1681.

She died in 1740 at the ripe old age of 80.

In more recent years, a “witch bottle” was discovered near Sherwood’s stomping grounds in Virginia Beach. The bottle was filled with sharp pins and nails and buried upside down. In Grace’s time some people believed that this was a way to redirect a curse back to a witch. Perhaps Luke and Elizabeth Hill spent one evening stuffing the collected items into the bottle. Perhaps they were genuinely afraid of Grace.

In 2006, on the 300th anniversary of the ducking, Virginia Gov. Tim Kaine proclaimed an informal pardon for Sherwood.

Today, Witchduck Road in Virginia Beach serves as a reminder of the time the court ordered a woman to be tossed in the river to prove her innocence. The Enlightenment couldn’t come soon enough.

Evangeline says

“Virginia Gov. Tim Kaine proclaimed an informal pardon for Sherwood.”

This was due to a lot of hard work and campaigning on the part of Belinda Nash, Director of the Friends of Ferry Plantation House in Virginia Beach.

Absolutely my favorite program. I have seen it twice, I just wish the records were still available to see what really happened.

Me too. It’s amazing how much we’ve been able to reconstruct given how much we lost. You have to wonder what it’s going to be like in the future with so many records disappearing into cyberspace.

Good one, Bill. Reminds me of this - wrong century, wrong continent, but same sentiments:

I love it!