For two weeks in September 1781, in preparation for what would be the pivotal battle of the Revolutionary War, Gen. Washington established his military headquarters at his friend George Wythe’s home in Williamsburg. Now, for the first time, visitors will be able to see what the house looked like during that crucial period just before the Battle of Yorktown.

From now until the end of February 2016, the Wythe House is Washington’s Headquarters. The high point of the transformation will come October 10-11 when “Washington’s Army Descends on Williamsburg” and the entire estate buzzes with the military business and activities that would have occurred in the run up to Yorktown.

George Wythe fled Williamsburg sometime in the months before Washington’s arrival, so the house was empty when American and French troops converged on the town. The family would have taken many of its valuables with them, rather than chance leaving them behind. The historical record is silent on the details, but Wythe may have skedaddled before British troops under Cornwallis occupied Williamsburg June 25-July 4, 1781.

The Wythes might have traveled to the family’s large plantation, Chesterville, in what is now Hampton, but to do so would have required crossing British lines. For that reason, some speculate that they went to Powhatan Plantation, Mrs. Wythe’s family homestead just a few miles away. In any case, as a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Wythe may have pledged his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor, but he wasn’t foolish to hang around in the face of British occupation.

We know from the Frenchman’s Map (likely drawn by one of the French soldiers in town) that the house served as headquarters. Rochambeau, another key leader in the final days of the Revolution, stayed in the Peyton Randolph House just down the street. The Marquis de Lafayette was also nearby.

The home’s transformation presents a fascinating contrast between the intellectual haven where the righteousness of the American cause was pondered and the martial environment where men made concrete plans to take lives in order to make independence a reality.

Gone are most of the adornments of Mr. Wythe’s tranquil and scholarly environment (above). Books and scientific instruments, and the harpsichord have been replaced by spurs, swords, and snuff boxes. And beds. Everywhere, beds. The globe has been put away, but a copy of the Frye-Jefferson map lies on a table in the parlor, suggesting the room was used for active battle planning (below).

So, you’re wondering, how did Colonial Williamsburg’s crack staff of conservators and historians know what to put in each room? Did some overachieving aide-de-camp leave a pen-and-ink diagram behind for posterity?

No such luck. There is no definitive guide on how the spaces were specifically altered when Washington used the house. But documentary evidence, including descriptions of Washington’s other wartime headquarters, orders placed for various goods, and knowledge of military necessities yielded many clues.

In Cambridge, Mass., Washington ordered a good quantity of Chinese porcelain. In Morristown, N.J., it was livery in the family colors for his attendants; in New Windsor, N.Y., “a traveling razor case with every thing compleat.”

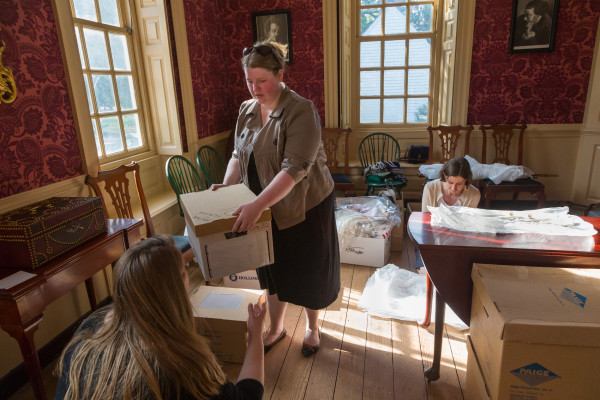

From the available evidence the conservation staff designed a furnishing plan. It’s a more-than-plausible arrangement based on what is known about the general and his encampments. And in just two days last week, the staff dismantled the Wythe House as we’ve come to know it and replaced dozens of new objects appropriate for Washington’s headquarters. (Ask them about how much bedding they had to prepare.)

Now, as you enter the house, you immediately encounter military equipment lining the hallway. The household is not arranged neatly to receive guests. Rather, it’s a working space free of frivolity. In the parlor, the game table is closed and the table is cluttered.

The dining room looks as if dinner has just ended. Hickory nuts were apparently a favorite of Washington’s, and their shells are all over the tables. Many illustrious figures would have dined here: along with Lafayette and Rochambeau, Col. Henry Knox, Gen. Edward Hand, and the French general Marquis de Saint-Simon.

Upstairs Washington’s aides had to be available to him around the clock and at a moment’s notice, and the beds illustrate the effort to squeeze as many as possible into the house. Even the general shares his room in this layout, with a cot for Billy Lee, the enslaved man who was at his side for the duration of the war.

There’s too much to describe here. You’ll just have to see it for yourself.

George Wythe’s House is open daily from 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. It will be open all day during the special program Washington’s Army Descends on Williamsburg October 10-11.

And don’t miss the opportunity to learn more about George Washington at the DeWitt Wallace Museum. Professor Peter Henriques will be giving three lectures on the general: The Early Years of George Washington’s Life on October 6; George Washington and the French and Indian War on October 7; and George Washington and the Coming of the Revolution on October 14. Click on the links for more information and to get your tickets.

Leave a Reply