Most of us would look at a tiny paint flake as nothing more than a speck that should be swept into the garbage. But in the Materials Analysis Lab, that tiny paint flake contains a wealth of information to help us understand the history of an object.

Most of us would look at a tiny paint flake as nothing more than a speck that should be swept into the garbage. But in the Materials Analysis Lab, that tiny paint flake contains a wealth of information to help us understand the history of an object.

An analytical technique called cross-section microscopy (CSM) allows us to determine the number and nature of decorative layers contained in each paint flake. When I was asked to determine the original finish on a corner cupboard from Norfolk (c. 1790-1815) in our collection, I knew cross-section microscopy would be my primary tool. At the time of the analysis, the interior of the corner cupboard was painted a light blue color, but areas of cracking and flaking paint revealed other colors beneath, including another blue paint as well as a pale yellow. We knew the current blue wasn’t original, but what was hiding beneath its surface? In this case, it was necessary to collect a paint sample to explore the possibilities.

As stewards of cultural heritage, we never want to remove a sample from an object unless it is absolutely necessary. So when we do collect a sample, we remove as little material as possible. Size doesn’t always matter! The smallest samples can contain an amazing amount of information.

Cupboards such as these are routinely stripped or scraped down to remove flaking or failing finishes. This means that I must look for finish evidence in areas that might have been protected from such campaigns, such as deep corners and interstices. In this case, the jackpot turned out to be a relatively protected area just beneath the top shelf. I used a surgical scalpel to remove a small flake of wood with the finishes attached. These samples are incredibly small (about 1mm across), but the evidence they contain is priceless.

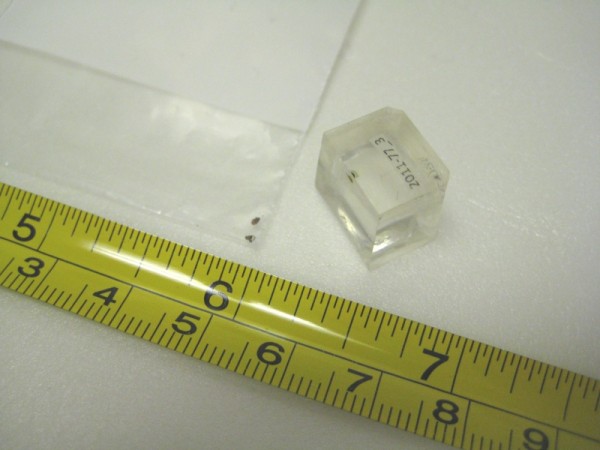

The sample is mounted in a cube of a clear resin, which, when cured, is essentially cut in half to reveal the cross-section of the paint flake. The surface is then polished (400-12,000 grit) to create a mirror-smooth surface for microscopy. When examined at 200x magnification with our Nikon Eclipse NiU epi-fluorescence microscope, the complete stratigraphy (layers applied over time) was revealed. There were six finish campaigns on the interior of this corner cupboard, starting with a thin deep red paint made with an iron oxide pigment (confirmed with PLM and XRF), that was applied directly to the surface of the wood. The grimy, cracked surface of this paint suggested it had been in place for a relatively long period of time, although an exact number of years could not be determined.

The pigment used was most likely Venetian Red, a red iron oxide pigment that is described as “a naturally occurring red ochre…Its color inclined “to the scarlet rather than the crimson hue. Venetian red does not fade, and works very well in oil” (Penn 1984:11). Other sources report it as having a “brick red color” (Gettens and Stout 1942:169). Venetian Red was regularly imported and used in Virginia in the 18th century:

“VENETIAN RED…Just imported in the Elizabeth, Captain Leitch, and in the Virginia, Captain Esten, from London, and to be sold by the Subscriber, at his shop in Petersburg…” (Virginia Gazette, June 10, 1773).

“VENETIAN [RED] GROUND…Just imported, and to be SOLD by the subscribers, at their store in Norfolk…(Virginia Gazette, July 25, 1766).

The tiny sample yielded another surprise- the second finish was actually not a paint at all, but a yellow-patterned wallpaper! In the cross-section, the paper substrate is the thick, brownish, translucent layer in visible light that has a bright autofluorescence in UV. The thin layer of bright yellow on its surface would have been the decorative pattern. The pigment responsible for the yellow color may be a chrome yellow, which dates this paper to c.1815 or later. (see my previous blog post for more info on chrome yellow).

Layers 3-6 are smoother, more consistent, and more finely ground paints, which suggests they were industrially prepared, and most likely date from the late 19th c. to the early 20th c., when the cupboard interior was most recently painted. Their ‘dim’ autofluorescence in UV is also common in more ‘modern’ paints.

So next time you’re sweeping – think of all the information contained in each tiny speck!

Else Travers says

Thank you for explaining all this so very well. The cross-sections are just amazing & that you get so much information from such a small sample is amazing as well. You make the history of these objects come alive. Well done!!

Many thanks! Glad you enjoyed it!