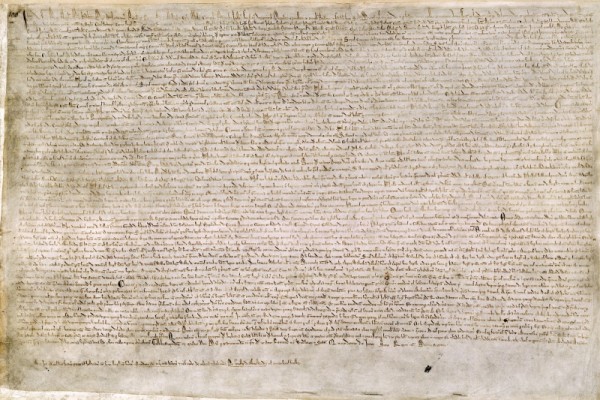

One of the four surviving copies of Magna Carta.

By Mac McKerral

Grantham, England — Americans might not appreciate this week’s anniversary of the signing of Magna Carta, but here in the United Kingdom, it’s a right proper big deal.

Attending one of the innumerable commemorative events, I found myself drawing connections between Magna Carta and the primary documents that helped shape the United States.

Dr. Alexander Lock, an expert on the post-medieval history of Magna Carta based at the British Library, placed the “Great Charter” more in the shadows than in the bright lights of human rights.

Lock came with strong credentials and a fascinating story to tell, and the British Library plays a significant role in the anniversary events — an anniversary that as Lock stated celebrates a document that Pope Innocent III declared null and void just 12 weeks after its signing by King John.

None of Magna Carta’s feudal law remains on the books today, Lock said. The document in essence was a peace treaty agreed upon grudgingly by King John and 25 barons out to oust him if he refused.

The vast majority of its 3,500 words (give or take) focuses on gripes those barons launched at the king for what they perceived as a series of missteps (failed wars against France) and injustices (taxes to pay for the wars, and to pay for royal marriages and other excesses of the king).

But stuffed unceremoniously in the middle of the charter, which King John signed under duress lest he face a civil war, came two clauses (of 63 total) with some legs — numbers 39 and 40 — that dealt with due process, habeas corpus and trial by jury: “To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.”

Of this we should take note, Lock said.

So why the big fuss over Magna Carta?

Lock landed on the age-old axiom: Perception sometimes outweighs reality.

Indeed, it took some 300 years before Magna Carta began to somewhat influence British law, more than 400 years before it served as a cornerstone for the British Bill of Rights in 1689 and more than 500 years before it helped lay the foundation for the Declaration of Independence, Lock said.

Renowned British barrister Sir Edward Coke in the mid-1600s used the charter extensively in launching his battle for the supremacy of common law over monarchial law, and he elevated the charter to symbolic status — a flag for the rights of the commoner, Lock said.

In fact, when it came to actual legal influence, Lock said the charter played better in the colonies than it did in England.

Coke helped draft Virginia’s colonial charter, Lock said. And William Penn drew heavily on Magna Carta. He founded the province of Pennsylvania with a large parcel of land deeded to Penn’s father by Charles II to pay off a debt. Penn because of his religious beliefs got sideways with British law all the time, but his arrest in 1670 proved most significant.

He landed in the Tower of London on charges of being a religious heretic and breaking a law that prohibited assembly. The judge, the Lord Mayor of London, refused to let Penn see the charges lodged against him — a right that flowed from Magna Carta.

A jury acquitted Penn, and the Lord Mayor threw the jury in jail and fined them. Their obstinacy led to the creation of a key legal right: English juries became free from judicial control. And the appeal process that won them victory also found its roots in Magna Carta.

But history aside, the point Lock made was that Magna Carta’s real measure of influence through some 800 years has been that of a propaganda piece rather than a foundation for human rights.

He cited a long history of it being used by lawyers, monarchs, parliamentarians and politicians to defend their sometimes diametrically opposed positions.

Many who never read the document or understood its influence on the law beyond fair trial issues, nevertheless used it as a battle cry for human rights.

And so Lock summarized that Magna Carta serves not as a significant legal document but rather a “powerful totem” of English liberty and legitimate political rights.

He reiterated this point about symbolism with a series of British historical nuggets and some U.S. nuggets, too: Magna Carta was cited during the Nixon Watergate Era and during the President Bill Clinton’s rough patch with Congress — in both cases in the context of presidents (monarchs if you will) not standing above civil law.

I smiled throughout this part of the lecture because in my experience, even though the U.S. Constitution serves as the basis for our law, it often gets cited and used (or perhaps abused) by those who want to make political hay and who do not understand its formation and the impetus for it.

And so Lock concludes that Magna Carta’s celebration really hinges on the symbolic engine it gained in the 17th century rather than what it did in the 13th century.

Since at its core the charter was an official piece of government paperwork, historians estimate official government scribes made 12 to 15 copies of the original 1215 document. Copies of subsequent re-issues of the charter (1216, 1217, 1225) number in the 20s. But only four known copies of the original exist. The British Library holds two of them. But Lock said more could be out there.

If you should stumble upon one, hold onto it. Estimates on the value of versions of the re-issued charters hover around 20 million pounds, more than $30 million.

Leave a Reply