Music Paper was used to prop the toe boards above the sliders to allow the sliders to move

By John Watson

Perhaps it seemed only natural that the original makers of the organ wind-chest chose old printed music to use as paper shims. The music paper was added to build up the thickness of the bearers so they would stand a single thickness of paper higher than the sliders, allowing the sliders to shift without binding under the toe boards (see wind-chest diagram).

I wondered whether the music could have been some old unsold stock from music merchants Longman & Broderip. L&B had recently gone out of business at the time James Longman, Muzio Clementi and their partners started Longman, Clementi & Co., producing this organized piano in their first year (1799).

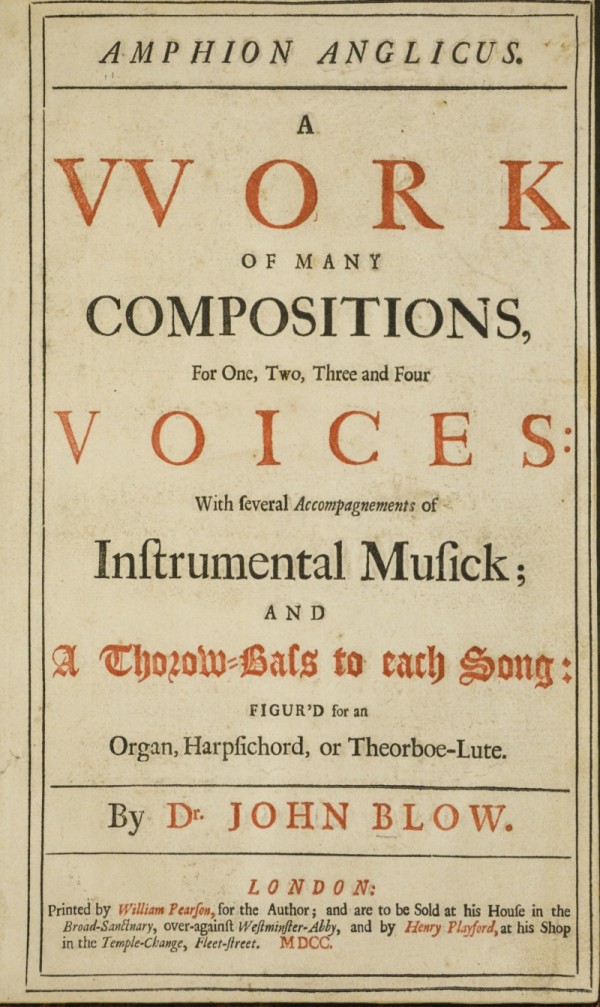

Title page of Amphion Anglicus, the anthology of music published by John Blow in 1700. Colonial Williamsburg Special Collections

Dr. Nikos Pappas came through the lab last week and spotted the music paper glued to the wind-chest. Nikos, a musicologist here in Williamsburg for a research fellowship at our library, made a surprising observation. Nikos pointed out that the music was printed using movable type. That technology for printing music had been replaced by engraving early in the 18th century. The music paper was much earlier than I thought.

Taking into account that some of the paper fragments had page numbers up to 204, Nikos knew that very few books of music in that early period had so many pages. He had already spotted one of them in the special collections of Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library. It was Amphion Anglicus, an anthology of music composed and published by the celebrated early English composer John Blow in the year 1700.

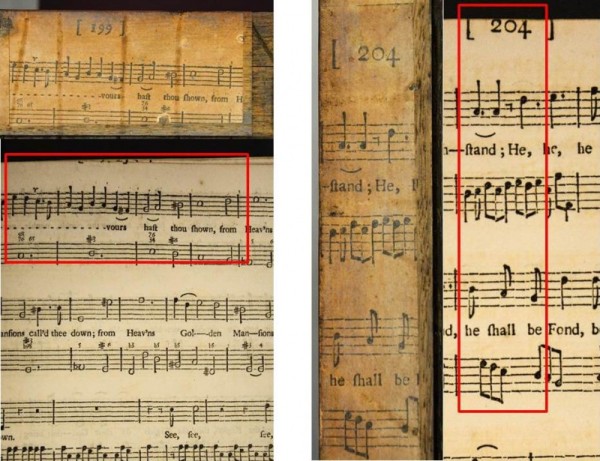

The next day, I made an appointment to see our original copy of Amphion Anglicus. With a photograph of one of the paper shims bearing the page number 199, I asked Doug Mayo in the library’s Special Collections to turn to page 199.

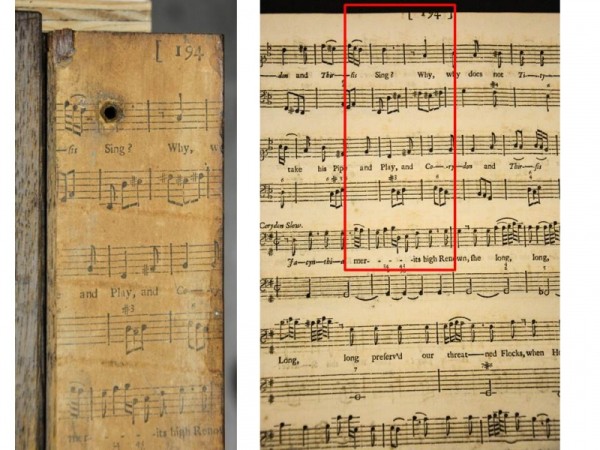

Two of the paper shims from the wind-chest (darker) next to the corresponding pages in the original 1700 publication. Colonial Williamsburg Special Collections

Voila! It was a perfect match.

The workmen had cut up what was already a 99-year-old book of music, composed and published by John Blow one year after Blow’s appointment as composer to the Chapel Royal.

Today, of course, no one would think of cutting up a first edition of John Blow’s Amphion Anglicus. Undoubtedly, Blow is venerated among today’s early-music enthusiasts more than he was in 1799. Perhaps the paper was the right thickness for the shims. Or perhaps the organbuilder just had a sense of humor, putting “Blow” in the wind-chest.

In the next post, we’ll look take a major step in the restorative conservation of the wind-chest.

Conservation of the Tucker organized piano is made possible by a gift in memory of N. Beverley Tucker, Jr.

[…] Finding “Blow” in the Wind-chest […]