Folding camp bed (1954-381) in the CWF collection. The bed has its original sacking which was the subject of this analysis.

Some analytical projects yield unexpected results. This week, I thought I would share with you one of those cases.

In our collection, we have a folding camp bed that dates to c.1770-1815, and includes the frame with its original sacking.

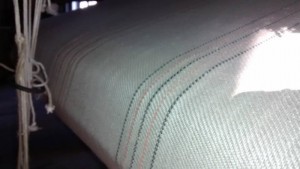

The sacking is made of coarse linen, mostly undyed but with some dark gray and light orange-red striping in the fabric. George Washington had a similar camp bed, which survives at Mount Vernon, but without its original sacking. Our historic trades have been busy making a number of reproduction objects for the First Oval Office Project that will be part of the new American Revolution Museum. A reproduction camp bed like George Washington’s was in order – using our camp bed sacking as the model.

Detail of the camp bed sacking, showing the faded black and red stripes. The paper arrows indicate areas where fiber samples were collected.

Before the weavers could reproduce the sacking, they needed to know what materials were used to make the colored stripes.

Examining the fabric up close, I noticed that the colored threads appeared to have been painted. Looking at the fibers under the stereomicroscope confirmed this observation: each fiber was encrusted with pigment particles. This was certainly not the dye we had expected.

photomicrograph of linen fibers encrusted with orange-red pigments. Reflected polarized light, 200x.

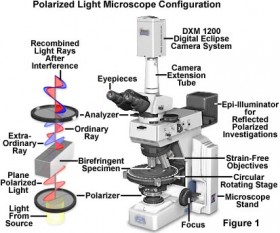

Using a surgical scalpel and micro-tweezers, I scraped some of the pigment grains off of the orange-red and gray fibers and examined them under the polarizing light microscope (PLM).

This type of microscope transmits polarized light through a sample so that at high magnifications, one can observe optical properties of particles such as their color, size, shape, and refractive index. This technique is used extensively in optical mineralogy and aids conservators and conservation scientists with pigment identification, since many pigments are, by their nature, minerals or share similar properties.

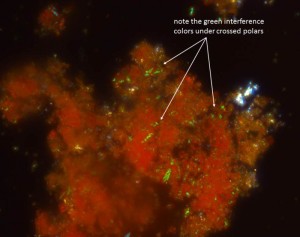

At 1000x magnification I observed that the particles from the red threads had a deep orange-red color, were mostly fine grained (1-5 microns), with rounded shapes. But this could be one of any number of red pigments. For further clarification, I engaged the analyzing filter (oriented at 90 degrees to the illumination) to view the sample under what is known as “cross-polarized light”. Under crossed polars, many of the red particles emitted a bright green color. This is known as an interference color, and this green interference color is diagnostic for red lead pigment.

- Dispersion of red pigments viewed with transmitted plane polarized light, 1000x.

- Dispersion of red pigments viewed with transmitted cross polarized light, 1000x.

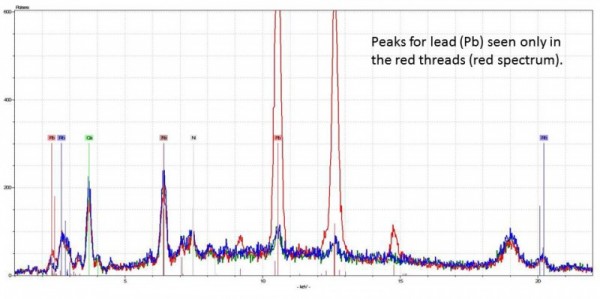

I was so surprised by this finding, I went back to the bed and double checked the red threads with our portable x-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF). XRF is a non-destructive technique that uses x-rays to detect elements above sodium (Na) in an object. Therefore, if red lead is present (Pb3O4) then lead (Pb) is detected. Sure enough, when the red stripes on the sacking were analyzed, large peaks for lead were seen.

XRF spectrum of red threads (red) overlaid with spectra from plain linen background (blue, green). Parameters: 40kV, 3.6uA, no vacuum and no filter, 15 seconds.

This was a definite confirmation for red lead pigment.

Red lead, or lead tetroxide (Pb3O4) is synthetically prepared by roasting white lead (2PbCO3 ∙ Pb(OH)2) or litharge (PbO). It has been used since antiquity and has been found on wall paintings in China and central Asia, in Persian and Byzantine miniatures, and was very common in manuscripts from the Middle Ages. For centuries it has been used in paints for furniture and architecture. In fact, in 18th century Virginia, red lead was commonly imported from abroad:

“Just imported…verdigrease, vermillion, white and red lead, linseed oil, gold and silver leaf….”

Thursday, April 13, 1769

Andrew Anderson and Co.

Virginia Gazette, William Rind, Ed.

“Just imported…gold and silver leaf….vermillion, verdigrease, red and white lead, painting oil…”

May 26, 1768

William Biers

Virginia Gazette, Purdie and Dixon, Eds.

In the historic area, red lead was specified for the roof of the Saint George Tucker House:

“The tops of the House, the roof of the Shed, and of the covered Way are to be painted with Spanish brown, somewhat enlivened, if necessary, with red Lead…”

Memorandum of an agreement made the thirtieth day of August 1798, between St. George Tucker and Jeremiah Satterwhite, both of Williamsburg; Colonial Williamsburg Archives.

Examination of the black threads determined that they were painted with a carbon black pigment. Carbon black is made from carbonized (burnt) organic materials such as wood or charcoal that are crushed into a fine, black powder. This pigment is found in many historic paints as it was widely available, inexpensive, and extremely stable and has been used since antiquity.

But why were the threads of the bed sacking painted, and not dyed? Our textile curators, conservators, and interpreters at the Weaver’s Shop had never heard of such a thing and could not find any reference to painting threads instead of dyeing them. Stranger still, examination showed that the threads were painted BEFORE being woven into the fabric.

Armed with this knowledge, the tradesmen and women at our Weaving and Dyeing Shop went ahead and painted skeins of linen with hand-ground red and black paint. (For safety reasons, they wisely decided to use another red pigment, red ochre, instead of actual red lead). I stopped by the shop while the work was in progress and snapped a few photos.

- Painting the linen skeins with red paint (photo: K. Moffitt)

- Painted threads ready for weaving (photo coutesy Colonial Williamsburg Weaving and Dyeing Shop Facebook Page)

It is always a thrill to see the results of our research take physical form in the historic area! Karen Clancy, journeyman weaver, spinner, and dyer at the Weaver’s Shop, reported to me that while the threads were stiff, they were still manageable for weaving. The final textile looks fantastic and is very accurate to the original appearance.

- Textile during weaving (photo courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Weaving and Dyeing Shop Facebook Page).

- The finished product (photo courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Weaving and Dyeing Shop Facebook Page).

We may never know why the threads were painted. Perhaps it was a cheap alternative to dyeing? Was this an experiment on the part of the weaver? For now it remains a mystery. But through collaborative projects like this we get a little bit closer to understanding historic materials and techniques that shed light on workmanship of the past.

To follow the progress of the camp bed reproduction, follow the First Oval Office on Facebook.

If you have any thoughts as to why the threads were painted, please leave a comment and let us know!

Thanks for reading and until next time, keep looking!

Depending on the time frame of manufacturing could the reason be two fold. First cost and possibly lack of supply of the ingredients to perform the dyeing process. In addition expediency may have been another reason. Painting and allowing the fibers to dry may have taken a shorter period of time to do versus the dyeing process.

Whatever the reason the use of paint to color the material is a fascinating mystery.