Photo of one of the pallets and a diagram showing its location in the wind-chest.

When working on the wind-chest, John and Lou noticed a white powder coming from the pallet valve leather – not a normal occurrence. This immediately raised questions for us. Was this a sign of deteriorating leather, necessitating replacement, or something more benign? Could the white powder be historical evidence, perhaps a 1799 method of helping the leather serve as a gasket? If so, it should be preserved.

Conservators deal with mysteries like this on a regular basis and they’re part of what keep us hooked. Someone needed to identify this white material and investigate why it was there. I got the job.

Pallets are valves that prevent air from entering the grooves of the wind-chest until a key is depressed and a specific pipe or set of pipes begins to sound. Once the key is released again, a metal spring makes the pallet snap shut, again blocking airflow (see Figure 1). Each valve is made from wood, with leather glued to the surface acting both as a hinge and as gasketing to prevent air leaks.

The soft, flexible, white leather used for the pallets is called alum-tawed leather, referring to the process used to convert the raw animal hide into a leather product. Alum-tawing is a long established technique in which potash alum is combined water, salt, flour and egg yolk to create a mixture which is forced into the hide. Filler materials, such as chalk, were sometimes substituted for or added to the flour.

Similarly, common fatty lubricants such as tallow, beeswax, lanolin or oil may have replaced the egg yolk. While alum-tawing produces a very soft, flexible product, it does not fully waterproof the leather, which would be ruined by water.

Though the alum-tawed leather from the pallet was in good condition, the powdery substance remained a mystery. Curious to know more, I dove into research and made use of Colonial Williamsburg’s Materials Analysis Laboratory, where conservator Kirsten Travers Moffitt helped me with more specialized analysis.

Based on initial research, it seemed that the white powder could be the filler mentioned earlier, perhaps flour or chalk. It could also have been alum from manufacture or later degradation. Another possibility was that the material was what conservators describe as a “fatty bloom,” a condition problem in which fats in leather crystallize on its surface.

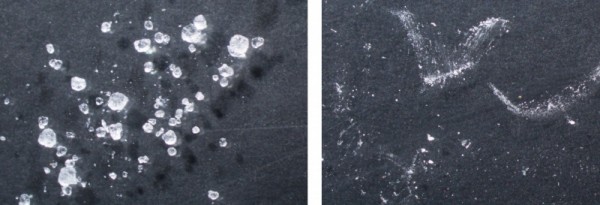

One of the first steps in analyzing a material is to observe it. I created two samples, mounted on glass slides: One of a known alum sample and the second of our mystery powder. Examined under low magnification, differences in physical characteristics were already apparent. Compare the two images below, taken at the same level of magnification.

On the left is a sample of alum particles as they appear through a microscope. On the right is a sample of the white pallet dust.

Beyond differences in look, the way these materials responded to manipulation with a spatula was vastly different. The alum, having little friction against glass, wanted to fly off the slide, while the unknown tended to smear. This led me to lean towards fatty bloom as an explanation for the powder.

Had I based my conclusions on look and feel alone, however, I would have been wrong!

The next step was to perform basic solubility testing. While this testing helped to confirm that the unknown wasn’t alum, it didn’t lead me much closer to the answer.

At this point, I collaborated with the Materials Analysis Laboratory to perform a type of analysis called Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR).

FTIR is frequently used in science and conservation labs and helps to characterize classes of chemicals (fats vs. proteins, for example). Analyzing the unknown sample showed it was chemically similar to calcium carbonate, also known as chalk.

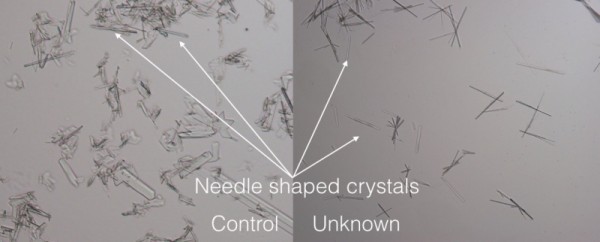

To confirm the powder was chalk I did two more tests — one for calcium and the other for carbonates. The test was positive for the calcium test as it resulted in needle-like crystals (shown below). The carbonate test, also positive, resulted in vigorous bubbling of carbon dioxide, similar to what’s seen when opening a bottle of soda.

Viewed through a microscope at 200 times normal size, the known calcium sample is on the left, and the sample from the pallet on the right.

We now feel confident that the white powder was simple chalk and was likely present in the leather as a filler or to improve the whiteness of the final product. It may be coming out of the leather now due to weakness in the leather fibers, reducing their “hold” on the chalk.

Conservation of the Tucker organized piano is made possible by a gift in memory of N. Beverley Tucker, Jr.

By Jennifer Schnitker

Leave a Reply