In 1926, Williamsburg was a quiet southern college town whose storied past had been largely forgotten. It hadn’t been Virginia’s capital city for 150 years and the modern world crept in slowly, with gas stations and soda fountains bumping up against old colonial buildings.

It was, in the words of one writer, a certain “R.G.,” “pleasingly decayed,” “a Highway Town in which the Ancient and the Modern were mingled in an Effect of peculiar Aggravation.”

But that was the year that the rector of a historic church persuaded a very wealthy benefactor with an appreciation for early American history to restore Williamsburg to its former glory.

The remarkable collaboration between the Rev. W.A.R. Goodwin and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. is a well-known story, but it occurred in circumstances that required the nascent institution to figure out how to cement its self-image in a hurry.

With the restoration and rebuilding barely underway, tourists were putting the old town on their itineraries in growing numbers. Enthusiasm for the colonial revival was strong and the automobile was revolutionizing travel.

How would Williamsburg tell its own story?

In 1928, Col. Arthur Woods, a Rockefeller adviser who had helped modernize the New York City police department as its commissioner, suggested it was time for an official guidebook.

Another adviser, Ivy Lee, considered by many to be the father of modern public relations, endorsed the idea. Lee wanted to take advantage of the growing buzz to introduce the “Williamsburg scheme” to newspapers, libraries and public figures who might be effective in publicizing the restoration. He proposed commissioning Henry Irving Brook, a native Virginian and writer for the New York Times, to do the job.

But it was determined to be premature to publish anything before the restoration was complete, or at least nearly so. Little did they suspect that the re-creation of the colonial capital would extend beyond their lifetimes and into the 21st century.

In the meantime, at the behest of the Williamsburg Holding Company (as the foundation was then known), the city had established a municipal guide service. To earn a license, a prospective guide had to pay a $5 fee and pass a test about the town’s history. (The city continues to license official guides today in the same way today.)

It soon became apparent that questions about the restoration project were outpacing questions about the town’s colonial history.

In stepped 30-year-old Rutherfoord Goodwin (above), whose father, the Rev. W.A.R. Goodwin, had instigated the enterprise in the first place.

In 1930, Rutherfoord had declared it “futile” to explain the project to the public yet. But questions multiplied as the curious increasingly found their way to Williamsburg. In the Atlanta Constitution, Thomas H. English wrote, “Already the dweller in the southeastern part of our country who has not made this pilgrimage is put rather on the defensive by his neighbors who have.”

So in the spring of 1931 Rutherfoord made the case that as long as they had to provide information to test official guides, they may as well publish a booklet for “the great number of tourists who do not employ the guide service and who regularly leave the city with an unfavorable impression of the undertaking or, more often, with no impression at all.”

Director of Research Harold Shurtleff agreed, commenting that an official publication might even provide “much needed protective propaganda against uninformed criticism.”

The resulting 48-page booklet included a brief overview and time line of the town’s history, four pages on the restoration, and descriptions of 82 buildings and points of interest. It was included with an admission ticket or it could be bought separately for 25 cents to provide a self-guided tour.

A future U.S. vice president, Nelson Rockefeller, declared the pocket-sized product “very appropriate for the situation” and sent his assurances that “Father will be pleased.”

Still, it wasn’t really a guidebook. So in 1933, as supplies of the pamphlet dwindled and the opening of the rebuilt Capitol building and Governor’s Palace approached, it was time for the real thing.

“We Are Almost Morally Bound”

The 1931 pamphlet had been, in Rutherfoord Goodwin’s phrasing, “pseudo-colonial.” Now they began to expand on the notion, deciding to pursue a design that, like the restoration itself, they hoped would be “startling in its authenticity.”

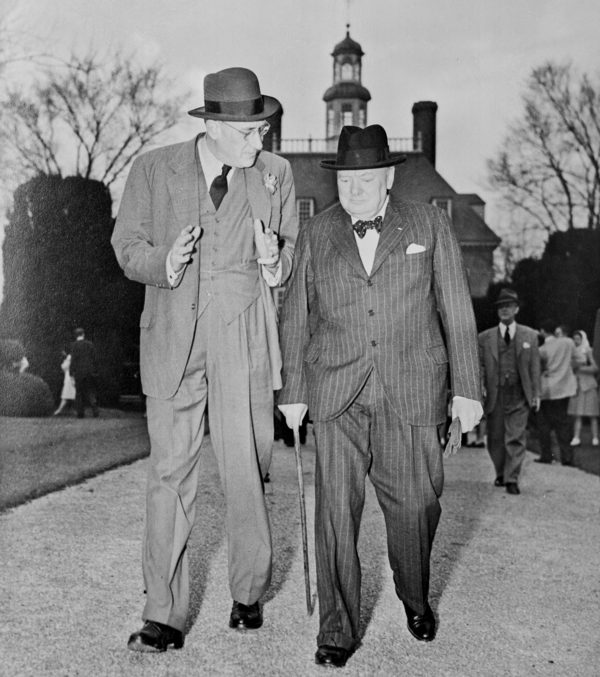

Kenneth Chorley with Sir Winston Churchill in 1946

Kenneth Chorley, Williamsburg’s vice president, wrote, “It seems to me that we who have worried over minute colonial detail in quantity and over a period of years are almost morally bound to give the public the first authentically colonial guide book on record.”

But what would an “authentic” guide to the colonial capital look like?

Everyone agreed that it should be different from the guidebooks for other historic sites, which were thoroughly modern, especially in the extensive use of photography. Instead they would try to adopt a colonial style in a package that would look like it had been recovered from a time capsule. What better way to advertise the lofty aims of the restoration?

“Both should be in the manner of the 18th century,” said Chorley, “for the colonial format demands colonial typography, and colonial typography falls flat without a colonial literary style. Nor should this style be considered alarming, for the 18th century writers said exactly what they meant without equivocation and their language was generally simple and direct.”

Such a guide promised to forge an emotional connection for visitors by helping them suspend disbelief in their visit to the 18th century.

Rutherfoord Goodwin, who would take on the writing assignment, pledged that the prose also would preserve the “flavour of antiquity.”

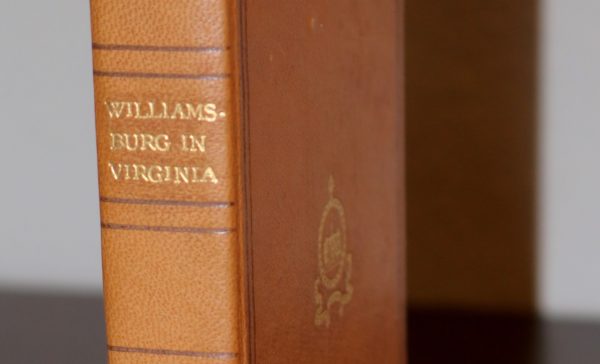

Colonial Williamsburg craftsmen began experimenting with ways to make the leather for the cover look older than it actually was. After a series of tests, they settled on the “antiquing” process, staining the leather pieces with a special mix of preservative grease and coffee.

The text approximated 18th-century style, which meant hand-set Caslon old-style type on “specially made rag paper.”

The guide featured “catchwords” at the bottom of odd-numbered pages and, of course, the characteristic long “s” (as in “Williamfburg”). A handful of engravings and a fold-out map were the only illustrations.

In early 1935, shortly before the guide went to press, Rutherfoord made an argument for retaining the long “s” in the face of apparent opposition. Specifically, a four-page argument for the long “s.”

“The keynote of the Restoration is authenticity,” he wrote. “Its buildings, while new in appearance, are accurate in detail. The newness is explained away with the fact that Williamsburg was new in colonial times.”

The requirements for the new guidebook were no different. “If it is to be authentic,” wrote Goodwin, “the modern use of the letter s would seem to fall in the same category with the use of machine pressed bricks as a veneer for the Governor’s Palace, an escalator in the place of the Capitol stair, or an elevator run to the Palace cupola.”

The long “s” stayed.

“A Happy Deception”

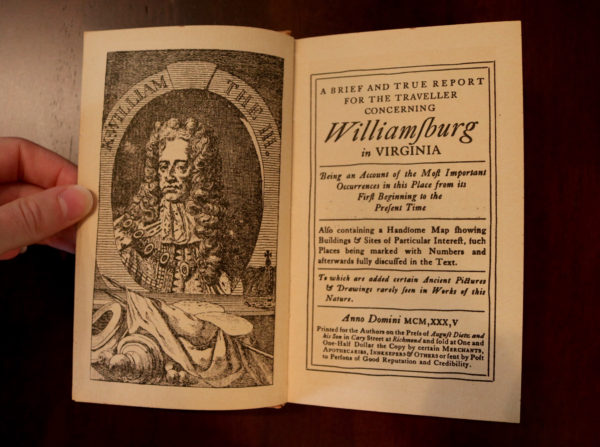

The spine of the guide read simply “Williamsburg in Virginia.” But inside, beyond the marbled end-leaves, the full title mimicked the lengthy titles so common in the 18th century:

A Brief and Thorough Report for the Traveller Concerning Williamsburg in Virginia: Being an account of the most important occurrences in this place from its beginning to the present time. Printed for the authors at the press of August Dietz and his son at Cary Street, Richmond, and sold at one and one-half dollar the copy by certain merchants, apothecaries, innkeepers and others, or sent by post to persons of good reputation and credibility.

Back in Williamsburg, Goodwin devoured each new press review as they were sent from Rockefeller’s New York office.

And the reviews were splendid. The “dainty” new guidebook was declared “charming,” a “happy deception,” “a book to be owned, read and prized.”

Several reviewers, and more than one letter writer to Colonial Williamsburg wondered aloud, “Who is this R.G.?” author of the curious time traveling guide.

Orders trickled in from shops across the eastern third of the country, where word of the ongoing restoration project was raising curiosity.

Bookstores as far away as Minneapolis and Montgomery, Ala., placed orders for the $1 leather edition.

Many department stores, including Macy’s in Manhattan and Woodward & Lothrop in Washington D.C., featured stacks on their book tables. But it was Miller & Rhoads, Richmond’s landmark department store on East Broad Street, that purchased the largest initial order, 350 copies.

August Dietz, whose Richmond firm printed the guidebook, kept close tabs on the book’s progress. “Recent conversations with book dealers,” he informed his Williamsburg partners, “leads me to think that this volume will out-sell many fiction items and will probably lead sales for Americana during the coming book season.”

The fold-out map in Colonial Williamsburg’s new Official Guide (bottom) bears a strong resemblance to the 1935 original. But much has changed in the colonial capital.

Within months discussions of a second edition began.

The 1935 guidebook was the first major expression of Colonial Williamsburg’s mission and purpose. Over the course of decades, through many new and revised editions, it is remarkable both how much and how little has changed.

Visitors to the colonial city come from a very different world than Goodwin’s. They encounter new buildings, new styles of interpretation, even a new guidebook.

But Williamsburg is still the place where remarkable events occurred, and where Americans go to meet and wrestle with our shared history. In the words of the author, R.G.:

“Good Friend, what matter how or whense you come To walk these streets which are the nation’s home Rest for a time and—resting—read herein Seek for the past and—seeking—Wisdom win For, if the things you see give you no gain, The Lives of many men were lived in vain.”

Many thanks to Anna Gorka, who shared photographs of her personal copy of the 1935 guidebook for inclusion in this story!

I happened upon this post and actually just ordered a copy of the 1935 guidebook. I can’t wait to see its artistry!

I received the guidebook, and it is beautiful! Here are some photos if anyone is interested: http://www.imgur.com/a/RSHBF

Great inspiring article of the thought that went into advertising and public relations. The 18th century style paper and binding seemed to be a great selling point in arousing curiosity and interest. Rutherfoord Goodwin’s quote at the end of this article summarized benefits of relaxation and wisdom while touching the guidebook reader’s conscience via “the things you see give you no gain, The lives of many men were lived in vain.”

Really enjoyed this article, so informative.

I have a copy of the 1935 Guide Book, picked it up at an antique book store in Virginia. I will definitely buy the new one and compare!