The wind-chest sits on top of the chassis just behind the upright grand piano. The organ’s pipes and outer casework are removed.

By John Watson

We’re back after some re-organization of the blog.

The series of posts by guest writer Jenna Simpson have been moved to the “History” page at the link above. Jenna details the fascinating story of the organized piano’s years in three celebrity estates in Virginia. The two most recent blog postings have now been moved there, with with two new segments added by Jenna.

Now back to the restorative conservation of the 1799 organized upright grand piano.

The wind-chest is at the heart of a pipe organ. Depending on the keys being depressed and the stops that were pulled, the wind-chest channels air from the bellows to the intended pipes.

The trick to making an old wind-chest work properly is being sure splits in the wood and failed glue seams do not allow air to leak from its passages through the chest.

If air escapes to the outside, it could mean the bellows have to work harder to supply enough wind. Or worse, air that leaks into the wrong channel causes stray notes to sound.

A close-up photo of the interior of the pallet box before treatment. It shows the pallets, wire pallet springs, and mouse nest.

And we have a whole lot of leaks.

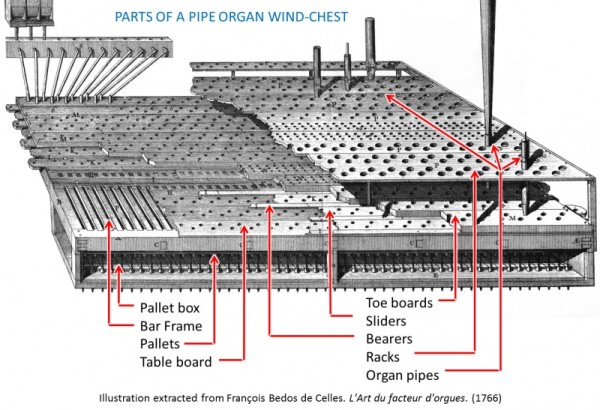

Drastic changes of humidity over the past two centuries have left the table board partially detached from the bar frame — the diagram below shows the name of the parts. For the past century or so, a mouse nest has hidden in the pallet box where pallets serve as valves, each pulled open by a key on the keyboard.

Not being house-trained, the mice also can be blamed for corrosion of brass pallet springs and the hardening of leather gaskets now unable to seal around the pallet box.

Traditional methods of organ restoration typically involve soaking wind-chests apart in a pool of water. That is an easy way to dissolve any remaining glue so the whole can be re-assembled with new glue. Many restorations of the past also involved replacing the thin table board with a new one of plywood.

Such methods can restore the function of the wind-chest, but we will look for other approaches that do not damage, discard or erase the historical evidence on old surfaces. Soaking the wood would mean indentations from various construction steps are lost, as are tool marks and old pencil marks left from the original construction. Some of the most important evidence on old surfaces may be as yet completely unnoticed. They await more sophisticated scientific methods of examination to reveal their part of the organ’s story.

It is precisely this kind of historic evidence that our restorative conservation methods are designed to protect.

In the next post, we’ll begin cleaning and treating the wind-chest. The challenge will be to clean surfaces and close leaks without discarding old parts or losing historical evidence.

Conservation of the Tucker organized piano is made possible by a gift in memory of N. Beverley Tucker, Jr.

[…] The Wind-Chest Before Treatment […]