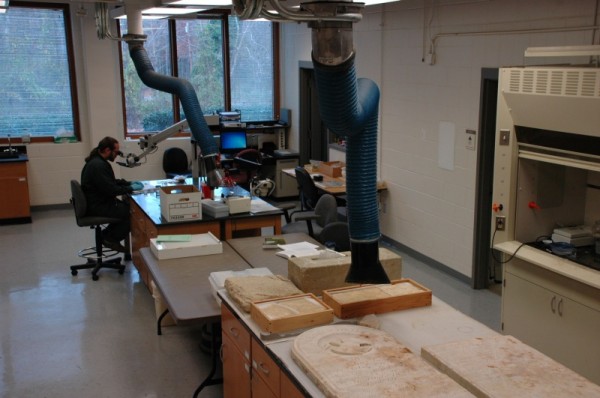

I spent much of this morning peering through a microscope at a little lump of corrosion that got smaller and smaller as I carefully picked away at it with a scalpel, until slowly it became identifiable as a coin. Unfortunately, at the end of all my work it was not particularly easy to tell whose coin it was.

I spent much of this morning peering through a microscope at a little lump of corrosion that got smaller and smaller as I carefully picked away at it with a scalpel, until slowly it became identifiable as a coin. Unfortunately, at the end of all my work it was not particularly easy to tell whose coin it was.

Viewing artifacts through a microscope helps archaeological conservator Emily Williams to clean with more precision.

There was a shadowy figure (possibly male) facing to the left but none of the inscription was legible. This is not always the case; sometimes we make really exciting discoveries.

One of my most favorite recently was finding these 18th-century repairs made to a fan blade. When the blade broke (I like to imagine that someone was making an impassioned point and rapped their fan too forcefully, though that may just be a flight of fancy on my part) its owner had a small piece of copper riveted to the back to hold it together. Later the fan broke again and was most likely discarded. For me, the discovery of this little mend created a link with the past. Both its owner and I felt that the object was valuable and wanted to preserve it… though possibly by different methods.

Modern conservation is a lot like archaeology. It is a slow process that gradually peels away layers of dirt and corrosion to find information. In this case, not the form of a building but rather the form of an object and information about the way it was used in the past. In the process, conservators also learn a lot about the people who used the objects.

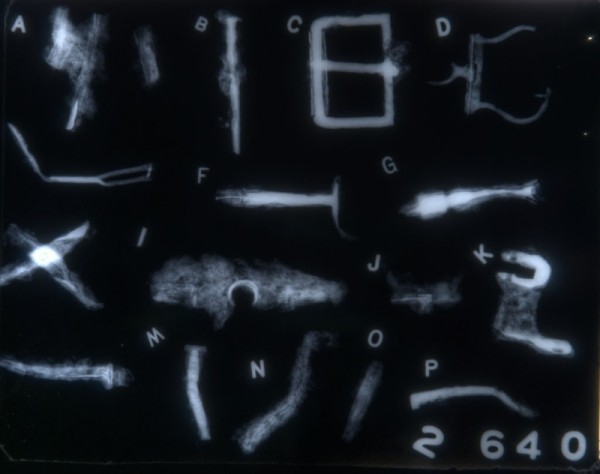

X-rays of iron objects can help conservators see beneath an artifact’s corrosion prior to treatment.

The goal of conservation (at least in an archaeological context) is not to return the object to what it looked like before it entered the ground. In most cases, this would be impossible. Salts and moisture in the ground cause metals to rust; bugs and microbacteria often eat the organic components of artifacts. Thus, a knife that might once have had a sharp and shiny blade and a wooden handle may emerge from the soil handle-less and fragmentary. Instead, the goal of conservation is to preserve the object from further damage. In the case of our knife this might involve soaking the iron in solutions to remove the chlorides that cause corrosion, and then later coating the object with an acrylic coating to prevent salts being transferred to its surface during handling (think how salty sweat tastes on a hot day and imagine what we leave behind when we touch things!!)

Intern Molly______ constructs s an archival box that properly supports skeletal remains of a dog.

Much of the time, conservators get to work on objects and to see them in intimate ways (up close under a microscope, taken apart, upside down or even in an x-ray) that others don’t get to share, but we also spend much of our time thinking about the environments we will put the objects into. Is the temperature right? Every 10 degree rise in temperature doubles the rate at which deterioration processes occur. Is there too much moisture in the air? Water helps to drive many of the chemical reactions that cause objects to deteriorate. What kind of materials is the object stored in? Archaeologists may love how easily small objects can be sorted in Dixie cups but conservators shudder at the thought of what contaminants might be transferred to the object from such non-archival materials. We spend time building boxes out of archival materials, providing support for fragile items, working with engineers and monitoring the environment. Conservation is truly a behind the scenes process. If we do our jobs well, you may not even know we have done it!

Contributed by Emily Williams, Conservator of Archaeological Materials

Wow, what a great post! This really inspires me; I want to be a historic conservationist some day!

Emily Williams says

Abby, I am so thrilled you are inspired by conservation! It is a great way to mix the sciences and the arts!

M Martin says

Nice article outlining museum conservation. And it’s always fun to see ex rayed iron.

Emily Williams says

Thank you! I agree, one of my favorite parts of my job is getting to be the first one to see what is inside all the iron”blobs” that come in form the field!