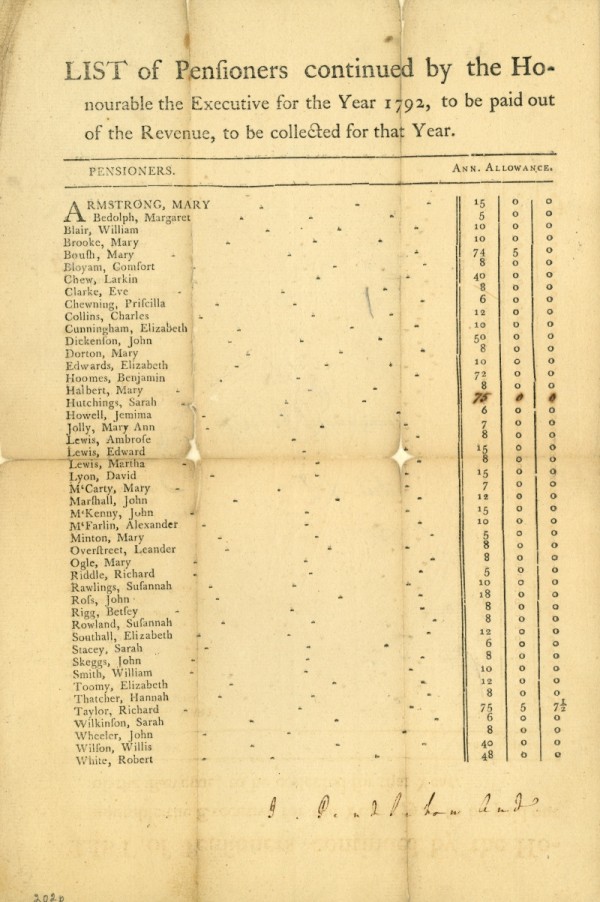

List of Virginia Revolutionary War soldiers or their widows eligible for pensions from the state of Virginia.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library Special Collections.

By Bill Sullivan

Veterans Day comes this year amidst ongoing debates over what we owe the men and women who have risked life and limb to defend our country.

The investigation into the scandalous treatment of injured sick and soldiers at VA hospitals continues. Congress has been considering what a 21st-century GI Bill should look like. And in Virginia, voters recently approved a state constitutional amendment extending property tax relief to the survivors of soldiers killed in action by a margin of nearly 9 to 1.

In some ways we’ve gotten better at honoring the military. But when resources are stretched, as they have been since the economic collapse in 2008, our best intentions bump up against financial reality.

The nation struggled with similar questions during and after the American Revolution.

Virginia’s General Assembly passed a pension bill in October 1777, authorizing payments to disabled soldiers and widows.

During the Revolution Virginia also dangled the offer of western lands in return for military service, not necessarily because it was the right thing to do, but rather to help the state meet its quota of men to fight the Revolution.

It was a generous program, promising anywhere from 100 acres to men who served out a 3-year enlistment to more than 3000 acres to a captain, and upwards of 5000 acres to a colonel. The land was in military districts carved out in the frontier territories of Kentucky and Ohio.

As the Revolution drew to a close in 1783, George Washington gave up his command of the Continental Army, but not without bristling at the notion that a half-pay pension was some sort of handout to his men. In his farewell letter to the army, Washington wrote:

As to the Idea, which I am informed has in some instances prevailed, that the half pay and commutation are to be regarded merely in the odious light of a Pension, it ought to be exploded forever; that Provision, should be viewed as it really was, a reasonable compensation offered by Congress, at a time when they had nothing else to give, to the Officers of the Army, for services then to be performed. It was the only means to prevent a total dereliction of the Service, It was a part of their hire, I may be allowed to say, it was the price of their blood and of your Independency, it is therefore more than a common debt, it is a debt of honour, it can never be considered as a Pension or gratuity, nor be cancelled until it is fairly discharged.

But there were occasional suspicions about the wisdom or legitimacy of paying ex-soldiers.

In Virginia auditors were responsible for recording and evaluating pension claims, a task they did as best they could with limited resources. Critics in the House of Burgesses expressed concern about possible fraud, worrying that a person could make claims in multiple jurisdictions.

In 1791 Virginia brought its pension system under the control of a single auditor of public accounts, who issued lists of approved pension recipients in order to ensure that only qualified veterans received state benefits.

Virginia’s policies during the Revolution were designed to induce volunteers to fight for the commonwealth.

We are doing much the same today, creating programs that ensure an effective all-volunteer military force.

Ultimately, we too are paying for substitutes. Keeping in mind what we are asking from the men and women of our military, we should not be counting pennies when it comes to their care.

Leave a Reply