Staff, Interns, and Volunteers gather to scrub oyster shells. Who says we don’t know how to have fun?

Last week we gathered together staff, interns, and volunteers here at CW’s Environmental Archaeology Lab to begin tackling the long process of cleaning, sorting, and analyzing more than 1,900 oyster shells recovered just from a single layer in the early 18th century saw pit uncovered during this summer’s Wren Yard excavation on the College of William and Mary campus. Each shell was sorted by side (left and right shells can be identified by the shape of the hinge-a live oyster has one left and one right shell), scrubbed with a tooth brush to remove loose dirt, and sprayed with clean water to wash off any lingering sediment that may obscure fine details on the shell. The field crew was kind enough to separate the oyster shells from other artifacts as they were excavating so we could wash them all in one go. You can imagine our excitement when they filled up 13 five-gallon buckets in the space of a few days. This is great news here in the Environmental Arch Lab, because we’re a little crazy for oysters right now!

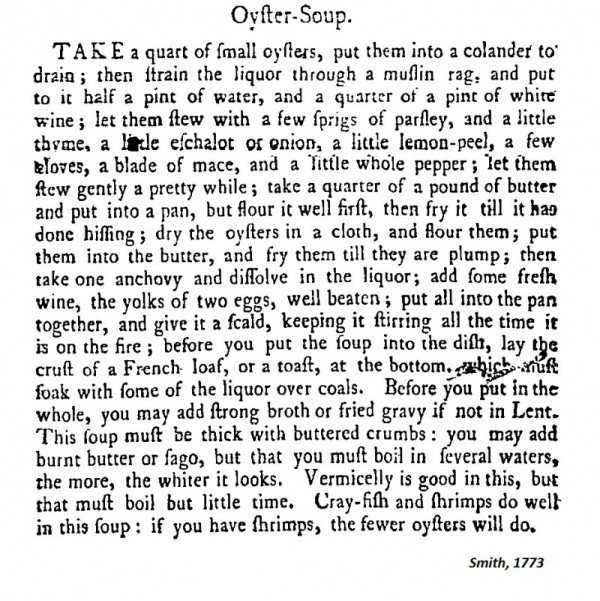

18th Century Recipe for Oyster Soup. Something to try!

Oyster shells are a very common artifact recovered from 18th century sites in the Chesapeake. They were a popular ingredient in colonial cuisine and their meat and liquor (the liquid found in the shell along with the oyster meat) were used to flavor many dishes. Oyster shells also had many uses other than as food: they were scattered across soggy work yards to keep feet out of the mud; they were burned to produce lime-an essential ingredient in plaster; and crushed oyster shell was mixed with lime, sand, and water to make tabby, a building material sometimes used in construction. Burnt and crushed oyster shell was even touted as a remedy for the bite of a mad dog in the Virginia Gazette in 1738. Archaeologically, oyster shells contain an amazing wealth of information about the environment oysters lived in, and even the season in which they were harvested. Oysters can tell us not just about what people were eating, but also about the climatic conditions in a region during a specific period.

Happy Oyster Washing Day!

Oyster shell analysis requires a high degree of specialized knowledge to unlock all that oysters have to tell us, from correctly identifying the types of parasites that lived on the shell to taking and processing tiny samples of shell for stable isotope analysis. The goal of the Environmental Archaeology Lab’s multiyear program of oyster shell research is to explore what the oyster shells from various sites throughout Williamsburg have to tell us about oyster use and distribution, the early market system in the region, harvesting methods, the climate in the colonial period, and how all these things changed over time. The Wren Yard oysters have a vital role to play in solving this puzzle in Williamsburg, and we’re looking forward to beginning the next phase of oyster research with these shells! (Please click on images to expand)

Contributed by Dessa Lightfoot, Environmental Lab Technician.

[envira-gallery id=”15977″]

Wendi, Hope your students enjoy the oyster info. Please let us know if there are other topics that they’d like to hear about through this blog. We take requests!

My students and I just finished up our archeology unit. They are experts in their own right. I can’t wait to share this article with them!

Thanks for a really interesting article. Makes me want to volunteer to be an archeologist’s assistant and learn about doing this cool study.

Jean!

Sorry you were not available for the Oyster Washing Party. We needed all the scrubbers we could get!