Market day for the “country people” started early when the stillness of the predawn hour in the capital was broken by faint and then distinct sounds of the rattling rumble of carts and wagons on the unpaved roads leading to Williamsburg. Traveling several miles from distant plantations or nearby farms those in vehicles and their neighbors who walked alongside carrying parcels, baskets, and small tables and stools converged on the broad open space in the center of town on the south side of the Duke of Gloucester Street just east of the magazine. These farmers were joined by resident butchers, bakers, and other people with goods to sell who set up temporary stands and more permanent stalls in the open-sided wooden market house that stood at one edge of a broad brick pavement.

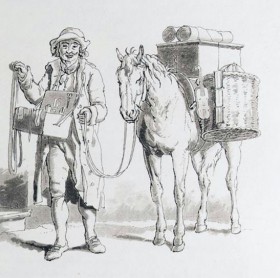

Within a very short time, they transformed the area into a shopping emporium with baskets filled with fresh vegetables, fruit, eggs, cheese, herbs, and gingerbread. Fishmongers with barrels of eels, fish, crabs, and oysters stood off in one corner where the smell of their catch would not be overpowering. All these stands were arranged within carefully delineated boundaries that marked the boundaries of the corporate market separating it from the area beyond where no such goods were allowed to be sold. After unloading their produce, tubs of butter, loaves of bread, sides of beef, and other items, the vendors led their horses and carts to nearby stable yards or pushed their wheelbarrows out of the way before they were told to do so by the city officials who were charged with overseeing the market. As dawn approached, the clerk of the market rang the bell that hung in the turret of market house, signaling to sellers and customers alike that the market was now open, an echo of which survives today with the clanging of the stock market bell on Wall Street.

Familiar in many respects to traditional farmers’ markets and more specialized boutique organic markets that have flourished in many cities in recent decades, the Williamsburg market in the colonial period was integral to the lives of all its residents for it was the place where they purchased most of the food that they put on their tables. Although some people raised chickens, fattened a pig or two, or tended small gardens to supplement their daily diet, their principal commodities could only be found for sale each week at the regularly scheduled public market. It was a busy crossroads in a town where people of all ranks, sex, and age met to do their shopping and to catch up on news and gossip that spread through the assembled throngs. City butchers and bakers in their rented stalls shaded from the sun by the overhanging eaves of the market house, country people at temporary stands on the pavement, and hucksters walking about crying their specialties hawked their goods to housewives, servants, slaves, and visitors. In Philadelphia in 1787, the Reverend Manasseh Cutler observed that “the crowds of people seemed like the collection at the last Day of Judgment, for there was every rank and condition in life, from the highest to the lowest, male and female, of every age and every color.” And so it was in Williamsburg like no other place in the city. (Click on the images below for a market day tour). [envira-gallery id=”15979″]

Carl Lounsbury, Architectural Historian.

Leave a Reply