Visitors to Colonial Williamsburg can come face-to-face with presidential history this President’s Weekend. To help your conversation, here’s some information on General George Washington circa 1775, Thomas Jefferson circa 1780, and James Madison circa 1790.

Each president is at a markedly different point in their careers and the development of the nation, with one thread linking them together: the enormous impact Williamsburg had on each of their civic lives.

General George Washington, 1775

The man who would later be unanimously elected President of the United States of America lost the first race of his career — a run for the House of Burgesses in 1755. Three years later, Washington succeeded in winning the Frederick County seat. He served as a Burgess from 1759-1774, during which time he formed a friendship with Lord Dunmore.

His letters to the last royal governor of Virginia, in which he frequently complains of Dunmore’s failure to visit him in Mount Vernon, speak of a close bond that would later be severed as colonial dissatisfaction with the Crown spread to Virginia.

As a legislator, he introduced Nonimportation resolutions to the Burgesses in 1769 and expressed his determination to preserve American liberties.

Governor Thomas Jefferson, 1780

When Thomas Jefferson first arrived in Williamsburg, he wasn’t terribly impressed, dubbing the town “Devilsburg.” Nonetheless, the young scholar would soon rise to a place of local prominence, attending House of Burgesses meetings as a law student and then practicing law in the General Court. One of his most memorable cases took place in 1770, when he defended a slave.

In 1777, Jefferson authored the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which asserted “…that our civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions any more than our opinions in physics or geometry.” The bill was introduced to the Virginia General Assembly in 1779, the year Jefferson was elected governor of Virginia.

Upon being reelected one year later, Jefferson chose to move the capital from Williamsburg to Richmond, which he deemed less likely to fall into British hands. His gamble proved unsuccessful when Richmond was burned by Benedict Arnold in 1781.

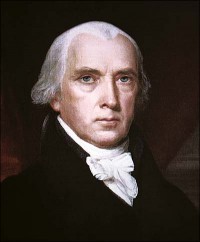

Congressman James Madison, 1790

Thomas Jefferson may have written the bill, but it took his friend and political ally, James “Father of the Constitution” Madison, to promote and pass the measure for religious freedom in the Virginia General Assembly.

Thomas Jefferson may have written the bill, but it took his friend and political ally, James “Father of the Constitution” Madison, to promote and pass the measure for religious freedom in the Virginia General Assembly.

Madison was born to a wealthy Virginian family but left the state to attend the College of New Jersey (Princeton), where he may have suffered a nervous breakdown from his long hours of study. After graduating, he returned home to manage the family plantation, Montpelier.

Elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1776, the young politician contributed to the creation of Virginia’s Constitution, kickstarting his reputation as an excellent statesman. Madison served on the Continental Congress during the Revolution and was instrumental in drafting the Constitution after the war.

In 1786, while Jefferson was out of the country, Madison ensured that his friend’s Virginia Statute for Religious Rights passed through the legislation.

Stop by this President’s Weekend to converse with these Founding Fathers. Learn about their illustrious political careers and come to understand the formative role that Williamsburg played in the birth of our country’s republic.

Jefferson and Madison’s combined efforts disestablished the Anglican Church in Virginia and ensured that “no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever.”

— Áine Cain and Claire Weaver

More information about Presidents Day Weekend.